Not So Recreational

by MADISON CAMPBELL | 3rd Place, student prose contest

When you’re young, you tend to think you’re invincible. You hear horror stories filled with bad luck and tragedy, and you think “that won’t happen to me.” It’s never until you’re in too deep or you get a reality check that you realize you’re just as vulnerable as everyone else. When I started abusing drugs, that was the mindset I was in. I told myself, it’s just recreational, it’s just on weekends, and it’s just to relax. Rationalization is a dangerous tool to those that know how to wield it. I was so nonchalant about my drug use; I don’t even remember the first pill. I do, however, remember the anticipation of the thirty minutes between swallowing it and waiting for the tingly euphoria of a blank mind.

At the time I started using, I had been dating someone for about a year and she and I had started our experimentation with pills together. We talked each other into continuous use, even though we knew it was dangerous. I was aware that all we were doing was putting a Band-Aid on deep rooted mental health issues, but at that time I didn’t care. You don’t feel depressed or filled with anxiety when you’ve numbed yourself out of sensation. Once we started, we never stopped. Well, at least one of us never stopped.

All it takes is one time and, before you know it, you’re someone you don’t recognize. Sober, I consider myself an honest person. I’m compassionate. I’m kind. On drugs, I spewed hate to those that cared about me. I lied, I stole, and I brought suffering to myself and others. When you use, it’s only a matter of time until you’re caught.

I don’t remember driving, and I don’t remember being arrested. I woke up in jail covered by a burlap sack of a blanket. My eyes blinked involuntarily, trying to adjust to the yellow glow of a single lightbulb fixed in the middle of the cell ceiling. When I could finally see again, I let out a shocked gasp at the sight. A metal toilet-sink contraption sat in the corner. Undignified as that may be, it was all I was provided. I lay on a concrete slab disguised as a bed in the opposite corner. Scared. Alone. Confused. The small bits I did remember of the previous night seemed like a horrible nightmare. Only flashes of blue and red crossed my mind as I squeezed my eyes shut trying to will my memory to fill in the gaps. They never fully returned. I spent the longest four days of my life in the general population of the jail until being bailed out.

That afternoon, when I got my car back from the impound, there were small indentations all along the top of the driver’s side door. I remember standing in front of it, pondering what those could be. When it hit me, I thought I might lose my jail sanctioned breakfast. They were from a cop’s baton. The arresting officer had to hit my car door to wake me up because I was in the driver’s seat nodding. As horrifying as that realization was, it wasn’t enough to keep me clean.

During my time in jail, I saw women who had ruined their lives with drugs, yet when I was back on the outside, I was high again within the week. That’s the thing about using: it starts out here and there for fun or to relax. Then it increases, and you only think about the next time you’ll get that release. Before you know it, you’re driving far or waiting long to spend your last few dollars on whatever you can get your hands on. It’s a slippery slope between recreation and addiction, and you never know how far you’ve slid until you’re damn near the bottom.

Four years of my life I spent chasing highs and passing up help. I knew what path I was heading down. My partner and I finally broke up. We had reached a plateau in our relationship where all we did together was drugs. Watching TV? Drugs. Go out and do something? Sure, but we better split a pill first. We had a long, exhausting conversation that ended in us separating. We blamed it on other factors, but realistically, I think we had differing opinions on how long we could keep up our current ways. I knew I would end up dead or back in jail if we continued.

When you step back and examine your life from the outside, your rationalizations tend to look a lot less rational. I had been to jail twice, I had crashed two cars (I was lucky enough to not have seriously injured myself or anyone else), and I had lost a few weeks’ worth of time being blacked out.

Shortly after the split with my partner, I met someone new, someone sober. One day, after my shift as a waitress, I bought the last two Xanax I’d ever buy from one of the line cooks—I know, shocking. I went home with my new partner who didn’t know I was using and swallowed one of them with a glass of soda I’d taken from work. I faded into blissful numbness, but I remember my partner commenting on how I was acting. “Are you okay?” she asked, followed up with “you’re acting different.” To which I probably replied something snarky and mean because I felt guilty. I nodded in and out of nothingness, but her words stuck with me.

The next morning, I woke up, managing to remember more of the previous night than I usually did. She left for work, and I lay in bed, still zoning, but drifting in and out of deep thought. Suddenly, hot tears streamed down my face. What the hell was I doing? A rush of guilt flooded over me like a dam breaking and I wept for what felt like hours but was probably only thirty minutes or so. Usually, the pills numbed emotion, but that morning the leftover high from the previous night seemed to elicit them. When I ran out of tears, I managed to drag myself out of bed. The remnants of last night’s inebriation made me wobble. I put a hand on the wall to steady myself and slowly made my way to one of my many hiding places. Anyone who has dealt with an addict knows they tend to have stashes everywhere.

I took the other pill I had bought and turned it over and over in my palm. My sweat drenched hands began to rub the coating off, which stuck to me and gave my hand a blue hue. Was I ready to quit? Was I even capable of it? I stared and stared at that little blue rectangle that had brought so much wreckage to my life until my vision blurred. “I am ready,” I told myself and squeezed my hand shut. I took the longest walk I’d ever been on to the bathroom and pulled the door shut behind me. Standing in front of the toilet, I turned the pill in my hand a few more times, only half noticing the parallel between my current stance and the time I had spent in front of the steel toilet in the isolation cell of the county jail. I dropped the pill into the water and pushed the handle down with more force than needed. I stood watching it swirl for too long, almost as if to make sure it was really gone. Finally, this chapter of my life was over. I had never felt lighter. A weight lifted off my shoulders, and I knew I was free from the grasp of the cycle I had been stuck in.

The next year was not easy. I had court fines. I had lost my license. I had court-ordered drug therapy. Most importantly, I had relationships to repair. I caused a lot of suffering to my loved ones, and it took a long time to let go of the guilt I held from that. I still get a knot in my stomach thinking about it sometimes. I had been blessed with a loving family and a supportive partner who all aided my recovery and taught me how to forgive myself through their forgiveness toward me. Now, I have been clean for five years. I completed all my requirements through the courts. I have my license, and my life, back.

Ω

Madison Campbell is a twenty-four-year-old, first-year college student. She enjoys spending time with her family, skating, and listening to music. Maddy wrote this piece after being given the prompt to write a story about resilience. She hopes it will stand as a cautionary tale to anyone in a similar position.

Hallie Fogarty is a poet, teacher, and artist from Kentucky. She received her MFA in poetry from Miami University, where she was awarded the 2024 Jordan-Goodman Graduate Award for Poetry. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Poetry South, The Lindenwood Review, Hoxie Gorge Review, Harpur Palate, and elsewhere. Besides writing, she loves cardigans, dogs, and everything peach-flavored.

What was Left to Us

by WINSLOW SCHMELLING

We drove the ‘77 Buick station wagon east on the highway because we didn’t know where else to take it. It was in the will. It was ours now. The lawyer, a man dressed in tweed I never knew Grandma had hired, handed the keys to us.

We were surprised when the car started at all. We’d known it for years as a long, fabric lump, half our lives with it spent covered in a giant sheet of canvas in our cluttered garage. In reality, it was a long, metallic lump, rust-colored, but on purpose. I think when the starter screamed and I throttled the gas again and again, Isabelle and I wished hard enough. The engine’s uncertain sputter ricocheted off the walls. It breathed unevenly and sent a rumble through the bench seat enough that I caught an Isabelle glance in my side-eye. We waited, we rumbled. The car’s rhythm settled into a less-volatile hum. I finally looked at Isabelle after clunking the car into gear, and then let loose a brief smile before the road devoured our attention.

We were still and silent as we exited the neighborhood from the house we shared with Grandma. The main road passed by blocks of chain-link-fenced houses and dirt yards full of car parts and Fisher-Price toys. We passed the convenience store with only two working gas pumps. We passed the Pacific Plaza strip mall where everything shared a sun-faded aqua tone meant to mimic the ocean, even though we were hours from the beach. We passed the wedge of the city that knew us before finally reaching the freeway ramp. We waited to breathe until then. We came up for air just above the city, buoyed by the interstate.

I earned driver’s seat by being five years older. Isabelle sat buckled in the passenger’s seat. She played with the window, the glove box, the mirror, the knobs in the door.

“What’s this for?” Isabelle asked, opening and closing the ashtray above the door handle.

“I think women used to keep their lipstick in there or something,” I said. Isabelle shut the ashtray with a squeak, clack. “They were really into their looks in those days,” I added sagely.

“Wouldn’t it melt?” she asked.

I shrugged. “Not everyone lives in the desert.”

The freeway was impressively empty, but I guessed that was how it worked after Sunday funerals. When the concrete wasn’t swarmed in all these lives and cars, you could see its sheer size, something of an architectural masterpiece. It was typical to be unaware of vastness then. We were two girls who had spent all our lives in the sticky flesh between the frenzied veins of southern California highways. Our California was just inland enough from the coast that it pretended to be lush and beachfront at the same time. It was neither. Instead, we had vertical lines of deep, waxy green plotted between freeway medians and corporate parking lots. Thirsty hills everywhere else. If you peeled it away, the drought was underneath it all, cracked and dried. Everyone who lived there knew to call it a desert.

Isabelle toyed with the knobs on the radio until she found a station she liked, some pop thing sung by boys barely older than her. She turned the chrome volume dial as far as it would go, then tried again in case it was stuck and could go further. It did. The song pumped through with surprising intensity considering at least one of the back speakers had gone out. Isabelle sang along, shouting it and bouncing in her seat, paying no mind to me in the driver’s seat or to the static thrum that obscured the boys’ autotuned voices.

We continued east. It was a direction, I think, we chased for the endlessness of it—east was infinity then. The ocean wasn’t boundless space; it was a wall. A stopping point. A reminder that places come to an end. We didn’t want to be stopped by the Pacific. We just wanted to drive.

I waited to change the station until Isabelle’s song was over. Finding stations by turning the knob on the radio was a skill, and each time I scrolled past the perfect spot I had to turn back again, keeping my eyes on the road. After a few commercials, several Banda stations, a nasal sports commentary, and a baritone NPR conversation, I stopped on a song. I raised my voice over the noise to Isabelle, and pointed at the dash, our little altar.

“Now here we go! This is what we’re supposed to listen to in this car,” I wailed, as David Bowie’s “Fame” blasted through three of the four speakers. There were few enough lyrics to the song, so it only took a few verses before Isabelle was shouting along, both of us screeching out our best falsettos in turn.

“Fame, Fame!” we screamed, and I guessed at the lyrics between, not quite sure but not quite caring. I mimicked Bowie’s voice, pointed to Isabelle on her turns and she’d answer me with another shout of “Fame!”

We sang to the road, now our road, the only one we could ever sing to like this. We’d intake our breaths before each verse, sucking in that smell that old cars have. It was a smell I think we identified with old people, not with old things. It didn’t smell like our grandmother, though. It just smelled like a time we never knew. Or it was all that time piled up in one place, kept inside a big metallic container, and covered with a canvas sheet in the garage. What did it mean that we were now inside of that smell? That now, with each whole breath between the verses of a song, it was inside of us? Isabelle closed her eyes and swayed inward to herself as she sang, like her heart was an easy pendulum. I keep the beat against the steering wheel.

The steering wheel of the station wagon was a thin one, so thin I could wrap my fingers around it twice if I wanted. Smooth, polished plastic with a strip of tortoiseshell through the middle. Every slight turn asked for a full rotation. The car itself drove with weight, any move accompanied by the swing of the car’s rear, all heft and heavy. After a turn, I’d just loosen my hands and let the wheel spin back in place against my palm, which made my skin sound like smooth leather or like sifting through the pages of a book. The speedometer’s highest speed read eighty. I was happy no one else was on the road, but even if they were, they’d know to go around. Driving her car was like driving a hearse.

The song ended and we fell into a noisy silence.

“June?” Isabelle said my name like a question. A scratchy-voiced DJ introduced some sad song by the Carpenters. Her eyes were glued to the orange-lit asphalt, immovable, yet flying past us.

“Yeah?” I said.

“We’re not going to be able to keep it are we?” she asked.

I watched as the streetlights flicked by. We were too low and surrounded by hills to see the city building behind us. You wouldn’t know from here that you were leaving anything, just entering more of the same. I didn’t answer.

It was just like Grandma to be acutely aware of what we wanted, what we needed, and to give it to us even if she knew it would be taken away.

Isabelle’s voice was a whisper, barely audible over the general noise that came with driving an old car on the freeway. Her eyes were a reflective gloss in the artificial glow of the city at night. I only heard her because I was listening.

“Let’s just keep driving,” she said in a tone made for sisters sharing secrets. With that tone, for all I knew, the road said it instead of her. The sound of it the same as a thick peal of tires against a river of highway that’s known a place so much longer than us. The road threatened to devour us whole then: the wild and unreal freedom that came with sitting still and driving, moving. We weren’t yet past the hills, too dark without the city lights, still trapped in that blind place of valleys.

“Yeah,” I said, and drove, like the distance would help me say something else. The lanky freeway streetlamps winked patches of evenly spaced light that we swallowed at eighty miles per hour. “Yeah,” I said again, but it did mean something else, for the way Isabelle’s shoulders turned inward, and how we knew the music wouldn’t get loud again. The road was still and empty, reserved for finished weekends. Before Karen Carpenter stopped singing about rainy days and Mondays, Isabelle changed the station back. She kicked her toes inside of her shoes to the beat of this next set of autotuned boys, but she didn’t sing.

The exits blinked by like a countdown. We made it to exit fourteen before we turned around and drove home.

Ω

Winslow Schmelling is a writer and maker from the Sonoran Desert and a recent graduate of Arizona State University’s MFA program in fiction. As an ex-professional pizza maker and a current content marketer, she feels lucky to also call herself a writer and a teacher in the desert where she grew up. Her creative work appears in LitHub, Welter Review, Heavy Feather Review, Wild Roof Journal and elsewhere. Find her at winslowschmelling.com.

Jasper Glen is a Canadian poet and artist. His work appears or is forthcoming in The Brooklyn Review, A Gathering of the Tribes, Posit, Word For/Word, Acta Victoriana, Collage.com.ar, and elsewhere. His poems have been nominated for Best New Poets and the Pushcart Prize. See https://jasperglen.com/

Homunculus

by JOHN CENTILLE | 3rd Place, student poetry contest

his pen, dripping extracts from a dozen vials

looks as real as the sword.

can present an instance as cutting

as its happening thanks to this assemblage

squeezed out from tomes, lives unlived

inside the study, a tepid gray.

look inside the latticed windows

and see the shadowed figure of a creature

creating from a source of life

he is not permitted to draw on

instead, throws out sheets of manuscripts,

commentaries, clever from a high perch

entirely unlike an everlasting scream

as no one ever sees the original pages

smeared nigh illegible.

and still truth seekers, undiscerning readers

dare to call his works plastic

a synthetic born from mere imagination

like a diamond’s authenticity could be determined

from a once chanced glance.

Tear him from his cage,

find your forged feelings to the letter

but do this and be prepared to look inside

his white spiderweb eyes that ask

what lies lie therein of human aspiratory lust

of self-taught strikers and world-worn genius

over that of the homunculus?

Ω

John Centille recently graduated from TCC with an AA in English. His favorite hobbies include breezing through manga, writing stories, and studying Japanese. He hopes to even do more of everything at NSU, but writing the most!

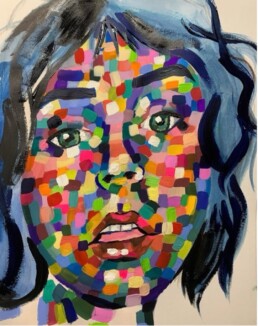

Jonathan Borthwick, a British-born cartoonist residing in Houston, Texas, is entirely self-taught. His cartoons primarily delve into the political and social dynamics of the United States in recent years. They strive to encapsulate a culture that feels foreign to him, employing a satirical style reminiscent of the popular UK cartoons of the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s.

criminal woman

by EILEEN PORZUCZEK

the fingerprints of society’s bloody hands

weigh heavy on me with sinister whispers

isolation suits you,

cultivate it,

rot in it

words laying heavy on my thick boned chest

as the oracles of prophecy gather to plot and

hide me, imprison me in attics of penitentiary—

my only crime against them being a strong woman.

Ω

Eileen Porzuczek is a creative writer, artist, and professional storyteller. She authors the poetry collection Memento Mori: A Poetic Memoir in Three Parts (Finishing Line Press, 2025), and some of her poetry will appear in White Winged Doves: A Stevie Nicks Poetry Anthology (Madville Publishing, 2026). Eileen’s poems also appear in So It Goes: The Journal of the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library, Creation Magazine, New Plains Review, The Raven Review, and in parentheses.

Linette Marie Allen is a graphic artist with an MFA from the University of Baltimore. Her images have been published in Quarterly West, Entropy, and Ripen the Page. A native of Washington, DC, she identifies as American BIPOC.

My Voice Isn’t Ready

by MEA COHEN

My mouth can no longer feel my name in it. To stitch this story together is to cauterize my lips. What precisely happened, years, days, hours ago: a blue night, cut with red. Words are whines, swelling from my throat, hindering expression. “Is that all you can remember” isn’t a question. It’s an illustration of tongue-tipped familiars, snatched by my teeth. My voice isn’t ready to carry this carnal weight. My jaws are resting, clefted apart by slight wind, enough for only necessary breath. Let the mouth do its infantile, dumb appeal for living. Though I am tired of pretending. What is the word for the realization that language can never save you? With my toothbrush, I scrub until maroon flies out of my gums and flows down into the porcelain sink. I dutifully wash it away. I draw breath and exhale. Give up on fitting into language. My teeth are picked clean. I growl at the mirror, and my heavy tongue goes slack. I am weaker than I seem. On the phone, my mother’s voice sings to me. She’s always singing. Her lyrics: “So, how are you?” I don’t sing back, my resolve acute in the locking jaw of the white bathroom. I hang up the phone and stick my fingers down my throat. My vomit is luminous in the toilet bowl. Luminous. My fingers are slick with gag slime. Through each new wound, the body chronicles just how many ways a person can suffer without words.

Ω

Mea Cohen’s work has appeared in The West Trade Review, The Gordon Square Review, OPEN: Journal of Arts and Letters, and more. She earned her MFA in creative writing and literature from Stony Brook University, where she was a contributing editor for The Southampton Review. She is the founder and editor of The Palisades Review.

Kiera Fisher is a Columbus-based muralist and mixed-media artist who embraces bold, brilliant, and vibrant colors and imagery to create art that makes you think, and makes your inner child jump for joy. She draws inspiration from her surroundings, incorporating lived experiences into her work, which frequently depicts figures and their relationship to people, places, and things. She works with a variety of media and materials, including anything from illustration and textiles to fine arts.

His Plan

by MARK LILLEY

Between benders my brother wants to take

his ten-year-old girl to the daddy-daughter dance.

He wants to do this right—suit and tie for him,

new dress for her, a corsage of yellow carnations.

His plan is dinner downtown with white tablecloths

followed by a carriage ride through the city,

and then the two of them joining her friends

to do the Macarena and Electric Slide,

enough effort that she might forgive him

for what he did to her mother in the front yard.

If he can make this night special, she might choose

to remember the string quartet on Market Street,

stars freckled above the city skyline, how he danced

the entire night without one stumble.

Just as my brother chooses to remember

a summer afternoon at Riverfront Stadium,

our father sober and holding his scorecard steady,

Johnny Bench hitting a deep fly to center field,

sellout crowd rising in unison, our father joining

the roar as we watch it sail safely over the fence.

Ω

Mark Lilley was born and raised in Cynthiana, Kentucky. He earned his undergraduate degree from Morehead State University and his MFA in poetry from Butler University. His poems have appeared in Atlanta Review, The Louisville Review, Poet Lore, Potomac Review, Red Rock Review, Southern Indiana Review, and other journals. His poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best Spiritual Literature Award. He currently lives in Fishers, Indiana.

Influenced by David Bowie, Virginia Woolf, and Sally Wainwright, Elinora Westfall is a lesbian writer of stage, screen, fiction, poetry, and radio from the UK.

The Nun of Melba Toast

by ELEANOR LEVINE

There are many fine moments in history: the post-Cold war period, the pre-Enlightenment era, and the Weimar era. I’m entering the post-Cholesterol Enlightenment era. I am learning there are great things to eat that are healthy: strawberries, peppers, cherries, peaches…also: edamame, seaweed…translucent low cholesterol…green and see through but comparable to algae, which, I’ve heard, is tasteless. Whether it is avocado or gluten-free Trump cupcakes, there is always a need for a meatier, finer substitute that transforms me from fat and indolent to youthful and spunky.

No one would know from my fat-cell indulgences as an adult that I once had a lithe figure—in my teens. I don’t know if it was high metabolism or my mom’s semi-bad cooking or my dad’s obsession with high-cholesterol products (he had a heart bypass and an existential crisis about fried eggs, though he cooked them), but it was not until I left the fold—the suburban-assimilated ranch along the highway (where Hasidic school girls now dance in delight in a building that has replaced what was once my house)—that I began to consume melted cheese and French fries and pizza.

My parents could not afford and/or allow us to order pizza or fries. No, we were a family that disavowed the notion of gratuitous eating that would later lead to a triple bypass, or the heart attack that was a result of a bag of Cheetos.

We had family issues around eating. Particularly my father. I suppose it was not the unhealthy things that threw him into a rage. He was used to that, and few of us deterred from our parents’ resolve not to bring junk food or butter or ice cream into the house—unless it was the rare occasion that we received an A- in algebra, when we celebrated with indulgent, high-cholesterol products such as Ben & Jerry’s. My father was mostly pissed if we tried something radically different, such as transforming into a vegetarian. Having grown up in the 1930s Depression era, Dad’s diet philosophy was, “If we have it, you’ll eat it.”

We were mostly like canines in our house, searching for the item that was indispensably bad for us, whether that be cheesecake or cheeseburger, which was not an option, because we were ostensibly kosher, not counting the times my mother brought shrimp with lobster into the house, or those intermittent occasions where no one mentioned the food’s heathen-like qualities and we ate unkosher products on paper plates. That occasional moment would have been okay if we did not also ruin my mother’s extensive silverware collection with goyisha ingredients that no Hasidic Jew would ever embrace—even on a molecular level.

So, it behooves me to say, that, at the Zionist socialist summer camp, where my parents sent me and my brothers, I was inveigled with people from all over the tristate area who dabbled in culinary digressions such as making fresh bread, eating tofu, generating cholesterol with gourmet ice cream, frying zucchini with mozzarella cheese and garlic, and serving pork substitutes. What really fascinated these fellow Zionists, some from a higher socioeconomic level than my own—in that their kitchens were displayed in elite architectural journals—was their fascination with food choices that diverted from the mainstream, middle class. You know, as my father would say, “things that wasted our money.” Thus, against my better judgment, and knowing full well it would cause my father cardiac arrest, I became a vegetarian.

In truth, the real motivation for becoming a veggie, though it was a short period in my not-so-long life (I was only sixteen), was that I liked Hildegaard, a trans girl at summer camp who did not know she was trans. She, like me, wanted to be a boy and easily dressed like one without much effort.

I strove to elicit low decibels with my deeper voice; I was smelly and klutzy and embraced nonfemale virtues that more resembled Charlie Brown than Lucy. I was not exactly Pig Pen. I was a higher echelon—above Pig Pen. Several inches higher than him (I am assuming this was his correct pronoun). I smelled and offered dirt enzymes to others for free, and the girls threw negative adjectives in my direction. Some even put a maggot or two (from the chicken shit on our camp kibbutz) on my bed. The worst was when they put a dead mouse on me when I slept, and I cringed more with embarrassment than fear.

Hildegaard, my veggie/crush/mentor, was quite popular, and when the other girls were outside or doing avodah (means “work” in Hebrew), Hildegaard talked with me, flirted, and joked about my disheveled manner.

“You are an adorable mess,” she said.

“Huh?”

“Well, my parents would never tolerate that drek on your bed.”

Hildegaard was blonde with hints of frost, but young enough where it looked completely natural.

“You’re a veggie?”

“Huh?”

“Are you a vegetarian?”

“No, are you?” I didn’t know her cuisine status initially because I was not permitted to sit with her. It’s like this with my love interests—they need to be haughty and unapproachable for me to like them. I normally sit with social-outcast girls with greasy hair and incoherent thoughts about NASCAR. We are all alone, while the girls at the neighboring table giggle over organic meals.

Hildegaard was closeted about her friendship with me, though it had a slightly romantic element; not being open about it preserved its mysterious and addictive nature. Hildegaard would stand a few feet from me—sneak a peek or give a blink—while we sang the proletariat song before entering the dining hall.

“Yes… you should try it,” she’d whisper about eating fewer mammals. “Get the lentils and tofu.”

Of course, it was trés difficile to change one’s diet at summer camp. You had to say you were a vegetarian at the beginning of camp, like asking for kosher meals in prison. Notification allowed the “authorities” to grant you esoteric food choices. I remained on a diet of mostly mashed potatoes, chicken, and green beans with an occasional hamburger.

Hildegaard, who was taller than me and a devoted athlete and noted scholar in an upstate New York private school, had a “crush” effect on me. The “crush” effect is when I fantasize about a relationship that does not exist.

In my brain we were sitting in a barn where she’d kiss me, though I envisioned she had another girlfriend. Not me. I was a flighty nerd who preferred non-Lauren shirts. Her chick was a refined preppy him. They both subscribed to The New Republic while I occasionally read Pauline Kael’s movie reviews from my dad’s New Yorker. They dissected flies. They hunted for rare mosquitoes. I picked jam from the jar or killed spiders. Hildegaard and her “friend” were on the debate team, whereas I was on the forensics team, and read the lyrics of Barbra Streisand at public speaking tournaments throughout New Jersey.

Thus, since this love affair only existed in my cerebrum, during and after I left camp, I became a veggie. I’d pay tribute to Hildegaard, extend the liaison (that did not exist) (except in my head) to the fresh produce at the local farmer’s market. A prolonged meditation on nonexistent poontang became the resolute worshipping of fried mushrooms and tomatoes. That was my religious altar. My vegetarian/Buddhist shrine to the Goddess of the Zionist-socialist camp: Hildegaard with blonde hair and pedigree green toenails that symbolized her spiritual attachment to all things green and down-to-earth and purchased at Anthropologie®.

Hildegard’s father was a veterinarian and an academic. Mine was a high school social studies teacher. My dad made less money, though he had studied at Columbia University’s Teachers College. (They didn’t let poor Hebrews into Columbia College in the 1940s, but Teachers College approved of lower-income Jews unable to pay for a chair in communications.) That my dad was a semi-member of the Ivy League—this was something I let people know, though our fragmented economic status did not endear me to people at the socialist camp or their relatives who raised money for the homeless and were photographed in the society pages of The New York Times. Indeed, if you were going to be a prole, you need to dress like one intentionally; these scrappy kids had an entirely upper-class ability to look impoverished.

It would have grossed them out that Stalin’s dad made shoes or that Stalin was mostly poor until he started killing his opponents.

Even Trotsky—who is riveting to socialist Jews from the Upper West Side—came from humble beginnings. His dad, I believe, was a farmer subsidized by the Russian government. Daddy Trotsky would not, in his odorous overalls, have ordered a sesame bagel with whitefish salad at Zabar’s.

After a month at camp—which was financed by a scholarship from my mother’s boss—I went home to Dad’s kitchen, with his Tupperware containers and canned vegetables and corn meal that we boiled and ate with sour cream and cottage cheese. Not like the wealthy chicks who ate mint leaves in their tea while posing with their dads in Bermuda. My father, who taught history during the year, was off in the summer and our chef in the kitchen (while Mom worked), though he was limited in his cooking skills—eggs and sandwiches. He also did a good pot of Campbell’s Tomato & Rice Soup and a superb Kraft Mac & Cheese. Whatever might be on sale at ShopRite.

“Daddy,” I said to him as he fried his eggs with loose yolks. “I can’t eat these dead birds.”

“What?”

“I am not going to eat the aborted fetuses of chickens.”

My father, who is normally even keeled (unless you eat before dinner and ruin your appetite), was not happy.

“You can’t be a vegetarian,” he said.

“Hildegaard is,” I said, thinking of her light ringlets and unshaved calves.

“Who the fuck is Hildegaard?” he asked.

“She’s my friend.”

In the seventies, in our house anyway, you didn’t want to tell your dad that you, a yet-unknown trans girl/guy, had a crush on another trans girl/guy/they who didn’t eat meat. Though my dad was a Roosevelt Democrat during the Depression era who wrote an anti-Vietnam War letter to the local paper (that almost got him fired), he could not conceive of the trans concept or the fusion concept or that pronouns would multiply, in forty years, like baby cockroaches. And the veggie shit, as stated earlier, was also too much for him.

“Why doesn’t she eat meat? I mean eggs?” my father asked.

“She thinks we are eating flesh and the baby of flesh.”

“Is Hildegaard a Roman Catholic?”

“No—a socialist from Poughkeepsie. Her dad is a professor at Vassar.”

“I don’t give a shit if he’s in charge of the New York Stock Exchange,” Daddy said, while my impudent brothers, whom I rarely spoke with (unless we were fighting) giggled in the background. They were younger and hostile toward me.

“Susan is not really a veggie, Dad,” one of my non-evolved siblings uttered.

“Mind your fucking business,” I roared. Being a foot taller always had an intimidating effect upon them and I shut them up before an argument or tangent flourished out of control.

“It’s really silly that you, who consumes more animals than anyone else in this house, suddenly prefers celery!” Daddy slammed the plate down. “Eat your eggs!”

I left the room.

About an hour later I snuck cottage cheese from the fridge.

A week thereafter I let him make me eggs. He fried the yolks. Made them firmer than usual. Put a little ketchup on the side, which disgusted me. Indeed, this was largely because my Hildegaard obsession flattened out. No internet or technology to stalk properly then and her phone number was unlisted.

Daddy was no Hildegaard. He was also not the current me with the indefatigable ability of non-stop inhaling whatever will terminate my existence at sixty-two. I am on borrowed time now, my friends tell me, because I chew food more than I ride the bike. And it is beyond the precipice of preventing a future stroke or heart attack, for I have been consuming a box of pizza every two days for more than forty years. If I had somehow mastered the Dad or Hildegaard School of Eating, I would not be in this post-apocalyptic predicament of over consumption.

My adulthood is the frying of cholesterol, and clearly, of course, the post-Cholesterol Enlightenment era where I should be eating tofu with hummus. My true nature, however, is gluttony. I would eat a dead platypus if I could sprinkle it with parmesan cheese. I love layers of sour cream in my vegetarian chili. I eat ricotta cheesecake like some might slurp spinach smoothies. I don’t do microscopic anything. I’m the antithesis of my once-thin body, where I would ignore obesity as you might a bad TV show.

But alas, I can no longer fixate on food as a religion. It must be as banal as walking your dog. Nothing dramatic will occur. My arteries will become less clogged and my soul less gluttonous if I dine on emblematic nothingness. Somewhere between veggies and egg yolks and Fried Oreos, I must rise from this dungeon of digestive chaos to be ninety-one, though I will be eating only Melba Toast. They will call me the Nun of Melba Toast. And I will shuffle my legs to the gym parking lot where I will quietly drive to a pizzeria and consume salads (not pasta) and live a proper few decades. I will have outlived my dogs, brothers, and parents, but be asexual, though not by choice. At least the Melba Toast—not the Fried Oreos from the Point Pleasant, New Jersey, boardwalk—will keep me fragile and thin. I will be like the dry-throated Labrador Retriever who wants ice cream but must settle for the brittle food in his dish.

Ω

Eleanor Levine’s writing has appeared in more than 150 publications, including The Hollins Critic, Gertrude, Raleigh Review, Notre Dame Review, Fiction, Faultline, and others. Her poetry collection, Waitress at the Red Moon Pizzeria, was published by Unsolicited Press (Portland, Oregon). Her short story collection, Kissing a Tree Surgeon, was published by Guernica Editions (Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

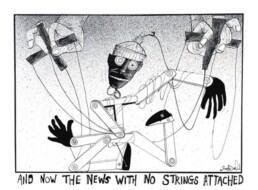

Sarah Jane Walker was born in Jacksonville, Florida and attended the University of North Florida, where she received a BA in Psychology in 2017. Her body of work usually conveys a story or an expression of a specific mood. With an obsession of English history, much of her work also portrays life in England’s past. She currently resides in South Carolina with her two kids.

Blameless

by ROBIN KOZAK

He has built in the rafters

of the underpass

as swallows build in the eaves of a barn:

a pink quilt folded tight

around a crossbeam, a cheerful quilt

printed with stars, or what passes in these parts

for stars at thirty

No feet dangle. No smoke

issues from the concrete chimney.

But I saw his breath

as I saw the President’s on television,

a flutter of substance, or substance’s lack, in the frigid air.

I flatter

myself, like Trump, in the television

lens of my imagining: I

am better there than here,

where I’m afraid of the homeless,

wino, bleary-eyed, stumbling, blowing his inescapable breath in my face

in Philadelphia,

in 1973 or thereabouts,

on a school trip.

I wore a pink dress I was proud of, short

in the fashion of those days, zippered tight

up the front, what they call

double-knit, warm enough for May

It fit as snugly as that quilt

fit the crossbeam,

the frail Hardy board

of someone’s house.

I longed

You’re pretty, the wino said.

I guess he meant it. But I ran.

Mr. President, you are a jerk.

That makes two of us.

Ω

Robin Kozak’s writing has appeared previously in Arkansas Review, Drunk Monkeys, Field, The Gettysburg Review, Hotel Amerika, Poetry Daily, Sequestrum, and other publications. Among her awards are two Creative Artist Program grants from the city of Houston and the 2016 Sandy Crimmins Prize for Poetry. An authority on antique and estate jewelry, she currently is finishing a work of magic realism, The Holy Grail.

Donald Patten is an artist and cartoonist from Belfast, Maine. He produces oil paintings, illustrations, ceramic pieces and graphic novels. His art has been exhibited in galleries across Maine. His online portfolio is donaldlpatten.newgrounds.com/art.

Pink

by CRISTINA MURANO

I unfolded my blanket.

It turned into a box.

I opened the lid of the box.

The box turned into a tent.

I entered the tent and there was a puzzle with one piece missing. I found the outlaw and placed it where it belonged. The puzzle turned into a well.

I sat on the edge of the well and then shifted my body so that the only thing between me and descending were my hands, which held tightly to the brick.

I let go.

Down I went.

Down.

Down.

My feet landed on a marshmallow. I laughed and reached down for a taste. My hand scooped at the white flesh, but then I discovered it was merengue with a hint of charcoal.

As soon as the goods hit my tongue, I grew five inches. The view became different.

I noticed a pink bird perched on a sunflower. I walked over and extended my arm and then opened my palm; to my surprise, the pink bird gently sat in it. The bird stayed there for minutes turning its head, staring at me, but not vocalizing a thing.

When it flew away, my body turned pink. Even my vision became immersed in pink. Pink was everywhere; it defined everything.

Not knowing how to differentiate between colors anymore, the world suddenly simplified and camouflaged, but it also opened possibilities.

How could I, like the bird, pass on pink?

In the distance I saw my blanket. I walked toward it, took off my shoes, and lay down. The sun looked opaque, but the sky looked like endless waves of joy.

Ω

Cristina Murano is an experienced professional with a demonstrated history of working in the public sector and communications industry. She has a flair for critical and creative thinking with work published in The Gwangju News Magazine and on her Substack, Reframing Difference, a project about the theory and practice of imagination. She holds a Master of Arts focused in Social Justice and Equity Studies from Brock University. She is based in Toronto, Canada.

Vivian Calderón Bogoslavsky is a Colombia Native. She holds a Bachelors in Anthropology with a minor in history, a postgraduate degree in journalism from Universidad of Los Andes in Bogota, Colombia, and a Bachelors in Fine Arts & Design from the USA.

Blackwork

by KALINA SMITH

I want to tattoo my body until there’s no skin left,

cover up the scars, raised and angry white,

ink up the heart inside my chest.

I’ll start with things you love, like music fests,

smoking weed, horror movies, and UFC fights.

I want to tattoo my body until there’s no skin left.

You’ll see butterflies and clovers when I’m undressed.

Song lyrics from late nights gone and floral scenes,

inking up the heart inside my chest.

The needles will become one with my arms

to cover the lines, remnants of cardiac arrest.

I want to tattoo my body until there’s no skin left.

In the center of my breast, I’ll dedicate to you a crest

with shades of purple, red, and green,

inking up the heart inside my chest.

So that maybe in my body you’ll become a permanent guest,

run your hands over the healed skin, white.

I’m going to tattoo my body until there’s no skin left,

black ink filling up the heart inside my chest.

Ω

Kalina Smith (she/her) is a teacher and poet. She has previously been published in Nebo, a Literary Journal, The Ignatian, FLARE: The Flagler Review, The Cackling Kettle, ONE ART: A Journal of Poetry, RedRoseThorns, Down in the Dirt, and The Wayfarer, and has work forthcoming in The Font, Porcupine, Superfan, and The Dawn Review. Kalina currently serves as poetry editor for Shadowplay. You can find her on Instagram @kalinasmithpoetry.

Janelle Cordero is an artist living in Spokane, Washington. Her writing has appeared in dozens of literary journals, including Driftwood Press, Jet Fuel Review, and Hobart, while her paintings have been featured in venues throughout the Pacific Northwest. Janelle is the author of five books of poetry, including Talk Louder (Tulipwood Press). As a fifth-generation resident of eastern Washington, Janelle has a deep love for cedar groves, lilacs, and small towns with one main street.