Coincidence

By ZHENYA YEVTUSHENKO | Sarah Stecher Prize, student poetry contest

after Miles Davis & Adrian Matejka

When a poet tells you to listen

to Jazz you listen to Jazz in a silent way

like Miles dancing in the trumpet of my pen, as we

remember how we howl with the unwritten, while someone else sells the world,

and the pen flourishes unfurled in furious fusion, like the modern fashion.

To think I could learn to listen like a coin listens to a lotto ticket,

or a toothache to a fang, its coyote stares as someone pours

cheap champagne onto a grave. God is a coincidence,

but also gives with each refrain, listen—shhh,

peaceful, another coincidence in the books.

Ω

Zhenya Yevtushenko is one of the sons of the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko. Zhenya aspires to become a public school teacher after graduation. He is a writer, occasional food service worker, and a literary event organizer. Zhenya's work has recently appeared in eMerge Magazine as co-winner of the Woody Barlow Poetry Contest. He owes his inspiration to his mother, his brothers, and the love of his life, Olivia.

Paul Acevedo is a Mexican American artist known for his large scale drawings that explore and celebrate his heritage. He was born and raised in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico, and his work reflects his experiences growing up in a Mexican American community. His drawings often feature images of traditional Mexican folklore and imagery, as well as scenes from daily life in his community. He is particularly interested in exploring the cultural blending and bicultural experience of Mexican Americans.

Lacuna

by ADAM DAVIS

I’m trying to appreciate

record skips, deleted scenes,

navels, chasms, entera,

white-outs and redactions,

the empty, gaping spaces

of atoms, cabinets, skulls,

the parsecs that divide us

from unfathomable stars,

parts no longer part of me:

baby teeth like craven

troops deserting one by one,

nucleotide deletions,

cells that burst and die

every seven years,

the 14 billion years

before my birth,

the looming future eons

that no cosmologist

will be alive to measure,

the third of life abed, asleep,

the increments of movies missed,

the guest rooms never occupied,

the last, badly timed

I love you on the phone

cut off since the other

interlocutor hung up.

Eventually, perhaps,

I’ll come to love blank pages

of the manuscript,

the measures full of rests

that depopulate the score,

but for now, give me fullness,

blue and blinding, everything

a million at a time

Ω

Adam P. Davis grew up in Maryland, majored in French at Wesleyan University, and received his masters degrees in political science at Columbia University and supply-chain management at Purdue University. He has taught English at several community colleges and spent a year in Shanghai. Currently, he works in the logistics industry. He has been published in Meniscus, Glassworks Magazine, Free State Review, East by Northeast Literary Magazine, and Silver Rose Magazine.

Paz Winshtein is a visual artist who lives and works in Los Angeles. Born in 1985 and in love with drawing from a very young age, the artist by age twelve was creating original oil paintings inspired by surreal painters such as Salvador Dali and Hieronymus Bosch. Winshtein's education involved different art classes from middle school and through college. At age nineteen, the artist began an art career by doing local art festivals, and soon expanded to art shows.

All the Little Creatures

by JAMIE CUNNINGHAM | 1st Place, student prose contest

Alice’s boutique was downtown, between an indie bookstore and a Jewish bakery. When the weather was nice, she liked to prop open the door with a heavy lawn ornament to let the rich fragrance of fresh-made bread waft in. On days when she couldn’t keep the door open, she burned a candle that smelled like baked cookies. She’d read somewhere that the aroma of fresh-cooked pastries put customers at ease, compelling them to spend more freely. Alice wasn’t sure about the science, but her shop always smelled nice.

As the new morning filled with sound and sunshine, Alice propped open her door, taking a moment to appreciate the morning sky marbled with wisps of milky cirrus. Next, she placed a large bowl of fresh water on the sidewalk. Alice loved dogs. The water dish began as a courtesy, but Alice soon found it was also an effective marketing ploy. As thirsty dogs paused to lap up the cool water, their owners window-shopped. Often, they quickly became patrons of Alice’s charming little shop.

With the door opened, the water dish filled, and the scent of bagels filling the store, Alice took her spot behind the cash register and began to look over her inventory sheets. Squinting through heavy-framed reading glasses to read, she cupped her coffee mug in both hands, relishing the warmth on her soft palms. Alice was increasingly aware that she was now of an age where her eyesight was diminishing some, and her hands were often cold. The flame of youth had long since dimmed, converting her once charcoal-colored hair to an ashen sheen. She’d come to accept her aging with grace and dignity, though she sometimes found herself lost in wistful nostalgia whenever young people visited her store.

She was about to pour herself a second cup when the motion sensor on the door bing-bonged the arrival of a customer. Alice installed the sensor so she could always know when someone entered the shop, even if she was in the back storeroom. Unlike her eyes, her hearing was still as sharp as a rabbit’s. Looking over the rim of her readers, she saw a young girl standing in the doorway, taking in the shop’s well-stocked shelves. Alice considered the young shopper with qualified discernment. The girl seemed harmless enough, though Alice had been fooled in the past by other seemingly innocuous kids. Alice recalled a charming little girl who kept Alice occupied with endless questions and stories while pocketing little trinkets and cheap jewelry. Alice realized she’d been bamboozled when the conniving child’s mother came to the shop to return the pilfered merchandise and offer apologies. Alice vowed never again to be duped. She closed her ledger book to keep a mindful eye on the girl in the store.

The girl was a slight little thing, around twelve or thirteen with a singularly acute and intelligent face. She was dressed in a breezy short-sleeved blouse and dark shorts, all arms and legs. Over one shoulder hung a small pink purse with the picture of a horse on the side. Alice acknowledged the girl with a welcoming smile and the girl responded with a wary lift of her chin. Then she turned her attention to a display of candles.

The girl’s head swiveled back and forth as she wandered aimlessly through the crowded aisles, occasionally pausing to pick up an item and quickly inspect it before returning it to the shelf. Eventually, her meandering path took her to the cash register. When the girl’s sweeping gaze landed upon Alice, she acknowledged the woman.

“Can I help you find something?” Alice asked.

The girl regarded Alice with a casual indifference. “I’m looking for something for my sister.”

“Wonderful. What’s the occasion? A birthday?”

“Sort of.”

Alice paused a moment to consider what a sort of birthday meant. Anticipating that she would have to lead the indecisive child toward a sale, Alice rose from her stool and came around the counter.

“So, you’re looking for a birthday gift for your sister. How old?”

“Old?” the girl asked, her eyebrows scrunched. “I didn’t know this was an antique store. I was wantin’ somethin’ new.”

Alice smiled. “I meant, how old is your sister?”

“Tuesday?”

“Her name is Tuesday?”

“No. That’s when she was born. Last Tuesday.”

“Ah. Six days ago?”

“Sounds ‘bout right.”

“Your sister is a newborn. Congratulations!”

The girl shrugged, unimpressed.

“What’s her name?”

“Just a second.” The girl sighed and opened her little purse. After a moment of rummaging, she came up with a crumpled piece of paper from which she read aloud. “Jew-LEE-uh Rose.”

“Jew-LEE-uh? That’s an interesting name.”

“It’s spelled just like Julia,” the girl said with a slight roll of the eyes. “But Dad and Rachel wants ever’body to pronounce it like that—mostly it’s Rachel’s idea.”

“I see. I guess that’s how the new generation does it.”

“It’s okay if you think it’s dumb. I do.”

“I’m sure it’s a perfectly fine name once you get used to it,” Alice said, though she privately agreed with the girl. Children’s names today were becoming awfully convoluted to spell and pronounce. Whatever happened to simple names like John or Mary or Tom? she thought to herself. “By the way, my name is Alice. What is yours?”

“Pepper,” the girl said, putting away her paper. “As in Sgt. Pepper? My mom was a huge Beatles fan. When I was little, we listened to all her old albums together.”

“Pepper. That’s cute.”

“Coulda been worse, I guess. Coulda been Eleanor Rigby or Prudence or Lucy.”

“You could have been the walrus.”

“Ku-ku-ka-choo,” Pepper chimed flatly. “So can you help me find somethin’ for the little slug, or what?”

“My shop is full of treasures. I’m sure we can find something around here for little, um, Jew-LEE-uh. How much money do you have?”

Pepper protectively covered her purse with both hands and said skeptically, “I think that’s my business, not yours.”

“You’re right. What I meant was, how much are you planning to spend?”

“I don’t know. She’s pretty new and all, but I suppose I could drop twenty bucks on her.”

“You’re a very generous sister.”

“She’s not my whole sister. Only half.” She made a chopping motion of her hand.

“A sister is a sister, no matter how many pieces she comes in.”

Pepper slowly turned away from the counter. “You got a lot of cool stuff here.”

“Thank you. I try to keep an assorted inventory.”

“You own this place?”

“I do.”

“I’m a businesswoman, too,” she said.

“Is that so? So you earn your own money…babysitting, perhaps?”

“Dad says I’m too young to sit on babies,” Pepper said while inspecting a display of ceramic birds. “I walk dogs for my neighbors.”

“Oh, I love dogs,” Alice confided.

“I did, too,” the girl sniffed as she moved to a table of tie-dyed tee shirts. “That is until I started spending my afternoons and Saturday mornings picking up steaming Labrador biscuits.”

Despite her no-nonsense delivery, Pepper’s voice still held the inflections of a child. Alice chuckled. “You seem very responsible for your age.”

Pepper looked over her shoulder at Alice and said, “I already told you I’m here to buy somethin’. You don’t have to butter me up.”

Alice raised her palms and smiled as Pepper returned to browsing the shelves. Satisfied that the girl was likely not a shoplifter, Alice returned to her perch behind the register and poured herself another cup of coffee. She decided against returning to her ledger as she noticed a small terrier out front lapping at the water dish. At the other end of the dog’s leash was a young woman dressed for exercise and admiring the ornate window display. Alice knew her next customer was just moments away, and she was not wrong.

“Is it okay if I bring Oskar inside?” the woman asked, holding up her end of the leash. “He’s usually well-behaved.”

“Of course,” Alice said, offering a pleasant smile. “Dogs are always welcome here.”

The athletic woman bounded inside with Oskar scrabbling along at her feet. She wore tight leggings worn by today’s youthful, health-conscious generation. Once again, Alice felt the bittersweet tinge of nostalgia wash over her like a mist of sea spray. She contemplated how different her youth had been compared to this hectic digital age. Everything and everyone moved so quickly now. Always on the go, Alice thought. Racing ahead, yet always behind. Not that Alice’s youthful days, fettered by poverty and toil, were ever ones of leisure. Certainly not.

The dog woman made her way around the store, pausing now and then to comment on how cute something was or to ask a price. Alice was always glad to engage and inform the customer. The boutique was in its twenty-eighth year of operation now, and Alice prided herself on her congenial customer service. Over the decades, she’d witnessed many neighboring businesses come and go, yet her shop remained, weathering the ups and downs of the mercurial economy. She attributed her success to good old-fashioned hospitality.

Eventually the young woman made her way to the counter with a gilded picture frame and a set of handsome onyx cufflinks. Alice rang up the sale and bagged the merchandise as the two women chatted amiably. Suddenly, Pepper appeared and crouched down to pet the terrier. Oskar seemed enormously pleased with the attention and licked the girl’s hand with all the enthusiasm of a puppy.

“He’s cute,” Pepper told the woman. “Do you have a regular dog walker?”

“Oh, well, no,” the woman admitted, caught off guard by the question.

With the flair of a seasoned street magician, Pepper produced a business card out of thin air and handed it to the woman. “My rates are reasonable and I have a good group of small breeds. I think he’d fit right in.”

Ambushed by Pepper’s pitch, the woman promised to discuss the matter with her husband. Alice and Pepper watched the woman exit the shop while juggling her purchases and Oskar’s taut leash. Once they were gone, Alice turned to the girl.

“That was pretty slick,” she said to Pepper.

“I need to expand outside of my neighborhood,” Pepper said. “If I get enough dogs, I can hire my friends to work for me.”

“You’re certainly full of ambition.”

“Dad says I get it from Mom.”

“My grandmother used to say, ‘Little girls always want to grow up to be their mothers and marry their fathers.’”

“That’s kinda weird,” Pepper said, giving Alice a sidelong look. “You sorta have an accent. You’re not from here, are you?”

Alice smiled politely, though she was inwardly disappointed. Since coming to America as a young woman, she’d tried hard to scrub any trace of her native accent. Usually, her vernacular was neutral, but lately, whenever she reminisced, she found her mother’s tongue surfacing.

“I was born long ago in a country that no longer exists,” Alice said cryptically.

Pepper thought that the woman must be really old to outlive a whole country—but she kept her thoughts to herself.

“I grew up under communism. Do you know that word? Well, let’s just say it was not a good place for children to grow up. I loved my homeland and my family, but no one liked our government. And in those days there was often violence and war between the people and the régime. I’ve always loved dogs, and when I was your age I had a dog named Laika who went everywhere with me. But I did not carry a pretty little purse like you do. I carried a rifle.”

Alice saw an expression of emotion pass over the girl’s stoic face, though it was a little hard to decipher. Was it one of impress or astonishment? Skepticism, maybe. Whatever it was, the girl was noticeably stirred. Pleased that she’d finally broken through Pepper’s stony demeanor, Alice resumed her tale.

“So many of my countrymen fled our homeland because of the fighting. Eventually, as a young woman, I was forced to escape to freedom with my little dog. Laika and I traveled across the Atlantic on our own, on a ship. First to Canada and later to America. I was all alone, barely sixteen and quite beautiful then. Don’t look so surprised.”

“I’m not. You’re still beautiful. You know, you should write a book.”

“A book? About what?”

“Your life,” Pepper said. “It sounds pretty interesting. People like reading about adventures.”

“It wasn’t an adventure. We were just trying to survive.”

“Well, people like that stuff, too.”

Alice considered Pepper’s suggestion. Write a book about her life? Much of her childhood had been simply insufferable. Who would want to read about that? But the child had a valid point. These days, there’s a market for everything.

“Anyways, back to my dilemma,” said Pepper. “I don’t know what to buy a newborn slug.”

“Maybe a nice ribbon. Does little Jew-LEE-uh have much hair?”

“I don’t know. I haven’t really seen her,” Pepper said and focused her gaze out the window. “Not up close. She was born a little early so they’re keepin’ her at the hospital in an incubator. Like she’s an egg that needs hatchin’.”

“The poor little thing.”

“Yeah. Her and Rachel have been in the hospital all week.”

“Rachel, is your…?”

“Stepmom. Every day, Dad and me come down to the hospital and check on them, see how they’re doing.”

“Did you walk here all the way from the hospital?”

“Yeah.”

“That’s about six blocks. I’m sure the hospital has a gift shop.”

“We pass by this place every day and I just thought you might have some neat stuff.” Pepper sighed, then looked down at her feet. “Besides, I hate the smell of hospitals. Reminds me of my mom. I had to get out of there.”

Alice heard the sadness in her voice. “Was your mother a nurse?”

“No. She had cancer and we spent a lot of time in hospitals before she…well, you never forget the smell.”

Alice understood immediately and placed a hand on Pepper’s shoulder. The girl flinched but did not pull away.

“How long ago was that?”

“When I was five,” she said softly. “Dad let me move her Beatles records into my room. When I’m feeling sad, I listen to them.”

Alice let silence pass between them, then removed her hand. Pepper looked up and met Alice’s gaze. The vulnerability in the girl’s big brown eyes broke the woman’s heart.

“Do you have other siblings?”

“Not that I know of.” Pepper grinned, regaining her poise. “That’s my dad’s joke. I’ve been an only child until now, so all this is kinda new to me.”

“I understand. I’m sure whatever you get for your new sister, she will love it.”

“It has to be the right gift,” Pepper said with steadfast determination.

Alice took note of the girl’s resolve. She surmised that finding a gift for Julia was less about the newborn and all about Pepper’s emergent need to give and to be needed. To find her place in this new and growing family. Life’s circumstances threatened to dwarf the girl’s ambition and it had prematurely pushed the girl towards an early independence. And now she was seeking acceptance from those she’d likely kept at arm’s length for a long time. Alice felt she understood all this because it had been much the same for her at that age.

“I think I might have just the thing for little Julia. Follow me.”

Alice led Pepper to a corner in the rear of the shop and was pleased to see the girl’s eyes light up when she saw a bin full of plush animals. With a jeweler's precision, Pepper methodically picked through the stuffed menagerie, evaluating each one before rejecting it and moving on to the next. Alice let the girl mine for the diamond in the rough she so desperately sought. Pepper spent a full five minutes in the bin before finally pausing with a teddy bear in her hands. She touched its nose and smelled its tawny fur.

“This one,” she said.

“Excellent choice.”

“He chose me,” Pepper said. “His name is Chauncey. The price tag says thirty-five dollars. Don’t suppose you’d take a twenty?”

Alice smiled. “You’re in luck. Chauncey is on sale today for twenty-five.”

Pepper smiled, too.

After completing the sale, Alice and Pepper moved to the sidewalk. Alice found herself saddened to see the girl depart. Pepper seemed reluctant to leave, as well. She gestured to the water dish on the walk.

“I like that you do that for the dogs. When I’m walking my clients’ mutts I have to take them all the way down to Baker Springs for a drink.”

“People these days are always in a hurry. They forget about all the little creatures.” Alice studied the morning traffic. “Shouldn’t you take a bus or a taxi, maybe? It can be dangerous for a young girl on these streets.”

“Did you take a taxi when you were my age? I didn’t think so. I’ll be fine. I’m a professional walker, remember?”

The girl took a few steps.

“Will you visit me again?” Alice asked.

“Sure,” Pepper said. She paused to look over her shoulder. “And you’ll write that book, right?”

“Oh, no one would want to read about me.”

“I would. See ya.”

Alice watched Pepper make her way down the block, waiting until the girl safely crossed the street before she returned inside. She took up her position behind the register. Alice picked up a pen and looked at it for a long moment, considering all the girl had said. Could she really write something that anyone would ever want to read? She clicked the pen a few times as doubts beset her lonely, daring soul.

Then she put on her reading glasses and wrote:

There once was a little girl who loved dogs…

Ω

Jamie Cunningham’s short fiction has appeared in such literary journals as Confrontation, The Iconoclast, and Tulsa Review. He is also an accomplished musician and skilled artist.

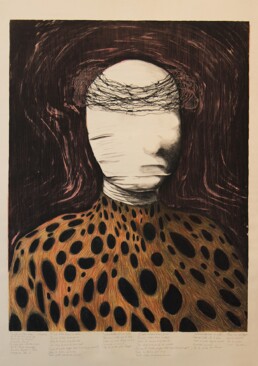

From Scout Haggard: A work that is always in progress as it changes as the artist changes, she is at a place where she feels completely herself even if that place is a little uncomfortable and confusing at times.

two electric currents

by HANNAH REGIER | 2nd Place, student poetry contest

sometimes being happy is what i’m most afraid of.

the holden caulfield worm-in-my-ear

calls me phony with each smile,

each giggle i use to entertain our audiences.

my figure blanks on what the other decided i would be.

two streams.

one floating rainbow fish, glittering

in the sunrays that flock to their scales.

the other holding my drowning fish of dark,

struggling with each new breath.

to travel between, one must pass

the roaring bank with the agility

i do not possess,

resulting in splashes and shivers.

differing diction covers topics

of my soft touch

to the ridges of regeneration

covering every inch of me.

of the cirrus clouds tickling

the blue sky of my soul,

to the stratus thunder shuddering

though my every muscle.

i encounter my cliff

and dive.

Ω

Hannah Regier is a freshman attending TCC for literature and philosophy (as personal focuses of her liberal arts degree). She admires poetry the most out of this written art form. She has recently published a poetry collection, a collection of things i found in my closet, and is hoping to be able to release more as she furthers her studies with literature.

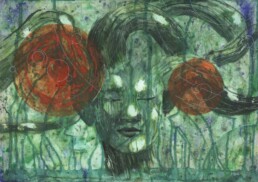

Zoe Nikolopoulou is a self-taught watercolor illustrator from Athens, Greece. She is also a poet and translator watching inspiration taking shape into paper. She discovered the magic of watercolors and continued to experiment with them after studying English Literature and Computer Science. Soon after, she opened an NFT account to promote herself.

Poor Johnny One Note

by LOREN STEPHENS

The beginning of a love affair foretells the end.

I handed Johnny the engagement ring he had given me—or rather I threw it at him. I could have kept it, I suppose. It had been made for me. I picked out a three-carat marquis diamond from a package of stones that he and his father had brought me from a store owned by Hasidic Jews in Manhattan’s diamond district. He had originally suggested that I wear his mother’s emerald ring, but it was too big for me, and I wanted something that was not a hand-me-down. Something that was exactly to my taste—understated elegance. I wore the ring set with baguettes in platinum for a month, admiring it while riding the crosstown bus to my job on Madison Avenue. I was proud of being engaged at twenty-one, no longer threatened by the specter of spinsterhood. I remember my father pressuring me in my senior year of high school, when I was trying to decide where to go to college. “At Smith, you’ll never meet anyone to marry,” he said. “Cornell is a better bet. There are lots of men there.”

My mother agreed. I interpreted their comments to mean that I was not pretty enough, sexy enough, or sophisticated enough to attract a rarified Harvard or Dartmouth man in the vicinity of Smith. At Cornell I dated a series of boyfriends who didn’t pass muster with my parents. Peter was the lifeguard at our country club and an engineering student. Not rich enough. Jeff was planning on going to VISTA; absolutely not. Norman dropped out of law school to avoid the draft for a year; he then ended up with a desk job in Saigon. Forget about him. Duke, an engineer who had a dance band, a single-engine airplane, and was Presbyterian. Too daring. And then there was Patrick, the heir to Rémy Martin in Bordeaux, France. Too old and my father forbid me from traveling with him across the United States no matter how I begged. I graduated without an MRS degree to my parents’ and Grandmother’s consternation. My grandmother had no filter. “What am I going to tell Cousin Ella?” she asked. “Her granddaughter is already married to a barrister in London. And look at you.”

“Grandma, please have faith in me. I won’t embarrass you.”

She grumbled. “You already have.” When I brought a boyfriend from Cornell for Shabbat dinner, she insulted him to his face, without a care that her comment was like a stab in the back to both of us.

I met Johnny Friedkin at a charity event for the Jewish Guild for the Blind, one of Manhattan’s most popular mixers within our social circle. He was six feet tall, a great dancer. Handsome, with large blue-green eyes and a thatch of blond hair that he kept brushing with his fingers whenever the front lock didn’t stay put. Could he have been any more sexy? We danced fast and furiously to the Lester Lanin Orchestra, and by the end of the evening, I was weak in the knees.

Was this the man who would turn my life into a romantic adventure? I wanted a big life. In the 1960s, I believed the mantra that women could have it all, just not at once.

On our first date we saw Dr. Zhivago at a small art house on Lexington Avenue. When we walked outside into the cold December night, the snow was falling, and my fur hat was quickly covered in glistening white snowflakes. Holding hands, we strolled up Third Avenue, looking into boutique windows like two flaneurs without a care in the world.

“Who would you rather be—Zhivago’s wife, Tonya, or his mistress, Lara?”

Without hesitating I answered, “Lara, of course. She was the woman who stole Zhivago’s heart.”

I went to bed that evening in the apartment I shared with my sister and her best friend, without Johnny. All I could think about was the boy with the fair hair.

Johnny told me he lived with his parents on Fifth Avenue across from the Metropolitan Museum but planned on moving out. He’d found a cheap studio apartment in a walk-up building in Yorktown occupied by Czech immigrants. It had a tiny kitchen with a bathtub covered by a cutting board, and the old-fashioned toilet in the bathroom had a pull chain for flushing. I had to be careful not to step on the water bugs and cockroaches that found their way up through the pipes. There was a sofa that turned into a double bed, which we quickly made use of, sometimes staying between the sheets for an entire weekend, except to go for Italian or Chinese takeout, or take a ride in his father’s Mercedes out to Jericho, in Oyster Bay, where he lived as a child. We’d put the top down, turn the radio up, and sing Frankie Valli’s “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You.”

The houses could only be described as mansions.

“Oyster Bay,” I said. “Isn’t this where Great Gatsby takes place?”

Johnny nodded. “It’s one of my favorite novels. I love the line, ‘So he waited, listening for a moment longer to the tuning-fork that had been struck upon a star.’”

“I expected you to quote the one about the ‘green light,’ but your choice is much more poetic.” I leaned over and kissed him as he drove top speed along the Long Island Highway.

Johnny played the guitar and confessed that someday he’d quit his job at Friedkin & Sons, his father’s insurance company on Maiden Lane, and devote himself full time to his music, but for the foreseeable future, he didn’t have a choice but to work for his dad. He said, “I’ll be like Charles Ives—an actuarial during the day and composing music at night.”

What he hadn’t acknowledged was that Charles Ives was a diligent music student at Yale and wrote a symphony for his senior thesis. Johnny played the same song he composed on the guitar over and over again. I wanted to believe with all my heart that someday he’d fulfill his dreams.

Mr. Friedkin, sliding his hand down his silk Sulka tie and waving the tip at me to get my attention, asked me, “Do you know what you’re doing, Elyse? You know that my son isn’t the most stable twenty-eight-year-old.” He looked sad and frustrated. “Johnny was a bright boy and then something went wrong.”

“Like what?”

“We don’t know. Sometime in his junior year in high school while his mother and I were in Europe and he lived in our apartment with two of our show business friends, he lost interest in everything. He was in and out of trouble. Now he’s not showing up for work. He makes up excuses.”

I sighed. “He tells me he doesn’t fit in.”

“Johnny doesn’t know what it means to put in an honest day’s work—maybe his mother and I spoiled him.” He stopped, took off his glasses, and cleaned them with a monogrammed handkerchief. I suspected a tear escaped from his eye. “Think about what I’ve told you, Elyse, and please keep our conversation to yourself. He should be grateful that he has somewhere to hang his hat.”

Mr. Friedkin’s company was founded by his father, Immanuel Friedkin, a German-Jewish immigrant who had recognized that insurance was a safe bet for making millions. Johnny’s father took over the reins of the company and made plenty of money to provide a good life for his family. Johnny was expected to take over the business when his father retired, whether he was equipped to do so or not. He dropped out of college and spent a few years as a ski bum and waiter in Colorado, until his father insisted he take the job that was waiting for him at Friedkin & Sons.

Johnny was so sweet to me, and so loving. He said he couldn’t live without me. He believed in me and encouraged me in whatever I wanted to do. Unlike my parents, he was my biggest cheerleader and my rapt audience of one. I had never felt so treasured.

One morning, as I was leaving his apartment, there was a basket of home-baked cookies on the door mat.

“Somebody left these for you,” I said.

He opened the envelope that was tucked inside the basket: Dear Mister Johnny. Tank yu for gitting my groseries. My legs are beter. How much I o you? Greatfuly, Missus Backorik.

“I’ll tell her she doesn’t owe me anything,” Johnny said. “Poor lady. She can’t afford even to see a doctor. Maybe I should pay the fee.”

“You better be careful, Mister Rockefeller, or you’ll be supporting the entire building.”

He fed me one of the dark brown sugar cookies and then licked the crumbs from my lips. “I’m going to be late for work,” he said. “I thought I’d wait a few minutes for the water to warm up. I hate taking cold showers.”

Taking a last bite of the cookie, I said, “I wish I could join you.”

I was still in the “love is blind” stage, and my parents were too distracted by my father’s mysterious illness to offer me the advice I so desperately needed. When I asked my mother what she thought of Johnny, she said, “He reminds me of my brother: handsome and slightly fey with a good sense of humor. Very charming. Do whatever you want, darling.” Comparing Johnny to her brother was a gut punch.

“Mom, what are you talking about? Uncle Harvey spent a year in a mental institution after the war. He’s never been quite right in the head.”

She adored her brother. Before the war, he was considered the most eligible bachelor—tall, with wavy blond hair and mischievous blue eyes. He had his pick of young women with his Yale diploma and acceptance to medical school. When the war broke out, he enlisted in the Navy and was sent to Normandy. Coddled by Park Avenue, he was ill-prepared for the horrors of battle and was diagnosed with shell shock.

My mother brushed aside his nervous breakdown. “He’s doing just fine now,” she said. She shooed me out of her bedroom and went back to playing solitaire.

At Christmas, Johnny’s parents invited me to join them for a performance of Man of La Mancha. When the lights went down, Richard Kiley stepped onto the stage, playing the role of the dreamer chasing windmills and the woman he loves. I wore a green velvet dress. Johnny ran his fingers up and down the fabric over my thigh and kissed my neck in the dark. During intermission I confessed that I felt like I was running a fever. His mother put her cool hand on my forehead and announced with confidence: 102º Fahrenheit. (My mother does the same thing; she thinks she is a human thermometer!) We stayed for the entire show—I didn’t want to miss a minute of it—but when the limousine dropped me off at my apartment, I took my temperature, called the doctor, and was admitted to the hospital with infectious herpes of the mouth and throat. Five days in the hospital. I was not allowed visitors. Johnny called me every day and sent flowers and Godiva chocolates. I couldn’t eat, so the candy went to the nurses.

Johnny snuck into the hospital wearing a doctor’s jacket. “How do you like my disguise?” He leaned over and kissed me.

“Don’t do that,” I said. “I’m catching.”

“I don’t care,” he said.

“You’ll care when you get what I’ve got.”

He kissed my hand and sang “All of Me.”

“Do you really feel that way?” I asked.

“I’ve been so worried about you. I never want to lose you.”

After I was discharged, the doctor warned me to slow down. His advice fell on deaf ears. My mother always used to say of me, “Elyse wants to run before she can walk.” Guilty as charged.

I was working long hours as a junior copywriter at NKJ, a Madison Avenue ad agency owned by my cousin, David Kaplan (of the “K”). I wanted to prove that I deserved my job, that it wasn’t nepotism that got me where I was so rapidly. Every night I went dancing with Johnny at Manhattan’s popular discos. He always seemed to have enough money to pay for champagne.

And then Johnny got the idea that we should apply for the Peace Corps. We snuck off to Washington, D.C., and took the admissions test. Neither of us had any skills that a small village in Guatemala could make use of, but for a crazy minute, we thought it might be fun, and we’d be trained on the government’s nickel to do something worthwhile.

He enthused, “Just think about it. I can get away from my parents. You too. We can be ourselves. No expectations, no judgments.”

I gulped. I did have expectations—a few years in the jungle, and then settling down to take advantage of my degree and become parents to 2.5 children. Johnny would become a famous songwriter, or if that didn’t work out, he’d give in to his parents’ expectations, buckle down, and take over the insurance business. On the side he could still play his guitar. Cielito Lindo, “El Dia Que Me Quieras,” a song of impossible love.

We stayed overnight at the Mayflower Hotel. With the rain pounding against the window, we ordered room service, and then spent most of the night making love. I asked him, “Why do you love me? I’m not as pretty as Julie Christie or as smart as Mary Wells or as rich as Gloria Vanderbilt.”

“I’m not exactly in their league, but if I were, I’d still choose you.” He wrapped himself around me.

“That’s not an answer,” I said.

“Well, we fit.” He hopped out of bed. Digging into his briefcase, which he was using as his overnight bag, he pulled out a book. Clearing his voice, he turned to a dog-eared page. “‘Courage is the root of beauty. And that’s what draws us to each other.’ Boris Pasternak. You don’t let anything get in your way. Whatever you want you go after.”

“I wish I believed in myself as much as you believe in me,” I said. “Maybe someday I’ll be your convert.”

A few weeks later, we got the results from the Peace Corps. I passed the test. Johnny didn’t. And then Johnny’s father fired him; his absences were proving an embarrassment. He was forced to admit that Johnny was ill-suited to the insurance business. Better to rip the bandage off quickly.

Johnny tried his hand at copywriting for a company that his father did business with. They hired him as a favor, but after a few weeks, he quit. He was miserable. By that time, we were engaged. I was madly in love with him and was under the illusion that I could straighten him out, despite all the warning signs to the contrary.

And then I didn’t get my period. I was petrified that I was pregnant. On the way to work, I went to St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Slipping into a wooden pew at the back, I prayed to God that I wasn’t pregnant. My hand was shaking as I lit a votive candle and stuffed ten dollars in the alms box.

That night, I told Johnny. He put his arms around me and, looking at me with his soft eyes, said, “You’ll make a wonderful mother.”

“Are you crazy?” I said. “We’re not ready to be parents. I can’t have this baby.”

“You’d have an abortion?”

“What would you suggest? You don’t even have a job. I’d have to support us.” I couldn’t believe what I was saying. All the pent-up rage and disillusionment came pouring out.

He argued, “We could live here. I’ll get a job as a maître d’ or a waiter at The Four Seasons until I sell my first song.” He looked around at the tub in the kitchen and the radiator. The smell of stuffed cabbage wafted in from Mrs. Backorik’s neighboring apartment. “This isn’t such a shabby place, is it? And we won’t be here forever.”

“You’re just like Don Quixote,” I sobbed and then I threw my engagement ring at him, tears running down my cheeks. My aim was bad. It bounced across the floor and slid underneath the radiator. We ended up on our hands and knees until he fished it out with a hanger.

Holding the ring between his fingers, he asked me if I was sure. I was tempted to tell him what his father had said. To spare him, I nodded, gathered my things and walked out the door, holding back another flood of tears until I was on the street.

I had to move on with my life. A few days after our breakup, I got my period. I telephoned Johnny. He sounded as relieved as I was.

He told me he had enlisted in the Army Reserve and was headed for a six-month tour of duty to Fort Dix, New Jersey. I thought about Uncle Harvey. I asked, “Will they send you off to Vietnam?”

“I sure as hell hope not,” he said. “In any case can I write to you? I might need a few words of encouragement. I’m not exactly fit for a mudhole.”

“I can’t promise that I’ll answer you,” I said. I was glad he couldn’t see the tears running down my cheeks. “Please take care of yourself.” Before he could say another word, I hung up.

I never saw Johnny again, as much as I wanted to, and I didn’t know what became of him until I learned years later that he had been involuntarily committed to a mental institution, too tender for this world. He ended his life by throwing himself off a bridge and drowned in the East River.

Ω

Loren Stephens has had essays and short stories published in the LA Times, Across the Margin, Chicago Tribune, The Expressionist, The Jewish Journal, The MacGuffin, The Montreal Review, Crack the Spine, Summerset Review, Umbrella Factory Magazine, and the Pennsylvania Literary Journal. She is president of Write Wisdom and Bright Star Memoirs, a ghostwriting company. Loren is a Pushcart Prize nominee, and in 2021 she published her debut novel, All Sorrows Can Be Borne.

Lily Elrick is a novice multimedia artist who creates art in copper and bronze, graphite, charcoal and acrylic paint.

Memi and Sabu

by JOSHUA KULSETH

after Philip Larkin

You’ve hardly any way

of explaining them apart,

hair plaited to the side,

arranged in stone together—

a guess only: the woman

a foot shorter. And her look,

as the plaque says, ‘oblique.’

Her eyes: adroit, intelligent.

His glazed and dull.

A space appears between them—

her embrace doubtful;

his, needful,

urging, stone-weariness

he’s brought to her, desperate

almost, to be soothed.

He palms her breast and stares,

she glances a little to the side,

her body swallowed.

Was it perseverance,

some instinct of passivity

that shaped her submission?

Or love hard as stone:

the moments that preserve us

coupled in difficult affection.

Ω

Joshua Kulseth earned his BA in English from Clemson University, his MFA in poetry from Hunter College, and his PhD in poetry from Texas Tech University. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Tar River Poetry, The Emerson Review, The Worcester Review, Rappahannock Review, The Windhover, and others. His poetry manuscript, Leaving Troy, was shortlisted for the Cider Press Review Publication Competition.

Jennifer S. Lange is a self-taught artist creating illustrations for books, games, posters, and worldbuilding projects. Her work has been shown internationally and in online exhibitions. She lives in northern Germany with her partner and a lot of cats.

Our Story

by SARAH RAY | 2nd Place, student prose contest

This story is dedicated to my dad. Through his telling the story of how he met my mom, I feel like I got a glimpse into my parents’ own awesome love story.

When Fr. Tom invited couples to come up to the front of the church for a marriage blessing at the end of Mass, no one expected first graders Matt Polska and Susie Anton to walk up there.

“As it’s the first Sunday of the month, any couples who were married in the month of April can come up here by the altar to receive a marriage blessing,” the tall priest said. He picked up his copy of The Priest’s Book of Prayers for Special Occasions, which had been a gift from his parents when he was ordained, and walked around the front of the altar to stand facing the congregation.

Several pairs of men and women stood up from various places around the circular church and made their way towards the front. The pews were laid out in a half-circle facing the altar, which stood on a slightly raised platform, and the crucifix that hung on the wall behind it. On a table beneath the crucifix stood the gold tabernacle, where Fr. Tom had just put the Eucharistic hosts that had been left over after Communion.

Susie’s mom saw her daughter stand up and start walking out of the pew. She reached over and grabbed her hand.

“Oh, Susie honey, it’s just for adults,” she whispered, careful not to wake up the baby girl shifting in her arms. “It’s a marriage blessing.”

“Yeah, Mommy. I gotta go be blessed,” Susie responded complacently, pulling her hand out of her mom’s grasp and walking confidently down the aisle towards the front. Mrs. Anton was about to stand up and run after her but didn’t want to cause a scene in church. She looked over at her husband and shrugged as their daughter walked away from them and toward where the priest was gathered with several married couples.

“Don’t worry,” he murmured, patting her hand. “I’m sure Father will send her back.”

On the other side of the church, Mrs. Polska was trying to get her youngest son to stay in his seat.

“I know you want to walk around, but Mass is almost done. You’ve been very patient.” She patted his hair.

“That’s right, son,” said Mr. Polska, who was sitting next to his wife. “Just one more song, and then we’ll get to go have lunch.”

All Matt said in reply was, “I’ll come back, ’kay, Daddy?” Then he turned around and ran out the other end of the pew, past his two older brothers.

“Wow,” muttered John, the oldest of the three. “He’d make an awesome running back.”

Mr. Polska leaned over to his wife and whispered, “Want me to go after him?”

She suppressed a smile and shook her head. “Just wait, dear,” she said. “I’m sure someone will send him back here.”

As the whole congregation looked on, Matt and Susie made their way toward the front from opposite sides of the church. When they met in the middle, Matt took Susie’s hand, and together they bounced along (Matt skipping, Susie kind of galloping) to where people were gathered at the front if the church, facing the altar. The adults standing there in pairs looked at them in surprise. So did Fr. Tom. Luckily for him, he’d taken an improv class eight years ago when he was in the seminary. He’d figured it would help him with answering people’s questions about the Catholic faith and the priesthood, and it had. But he’d had no idea that he would need it to give a marriage blessing!

Thinking on his feet, Father stroked his short beard and said, “Before we begin this marriage blessing, I’d like to start by asking each of the couples how long they’ve been married, where they got married, and if they have any other details about the ceremony they’d like to share. Mrs. Hubbard, can you start us off?”

“Certainly, Father,” she replied, with her characteristic toothy grin. “George and I were married in Raleigh, North Carolina, sixteen years ago. Isn’t that right, George?”

“It sure is, honey,” Mr. Hubbard said. “It was right before I accepted my job here in the Midwest and we moved halfway across the country.”

After hearing about the Wyatts’ wedding during the Vietnam War (“I still have my lace veil,” Mrs. Wyatt proclaimed), and the Youngs’ wedding last year (“Fr. Tom officiated, and it was held right here,” they said), it was finally Susie and Matt’s turn. Everyone looked at them curiously, most of all their parents.

“So, where’d you young ’uns get married?” Fr. Tom asked, though he wasn’t really expecting an answer.

“Here,” Matt said, bouncing from foot to foot.

“In the church?”

“No, it was at the playground,” Susie responded.

There was mild laughter from the congregation.

“Yeah,” Matt continued. “On Friday we learned about the Sacrament of Holy Macaroni in religion class.”

“You mean Holy Matrimony?” Fr. Tom asked.

“That’s what I said!” said Matt.

“Yeah,” said Susie. She took hold of the sides of her purple sundress and began to swish it around her legs as she talked. “See, after we learned about Holy Alimony, we had recess and I…I picked some flowers. Well, they’re those little purple flowers that my mom says are weeds but I think they’re pretty, so I picked them and I found a napkin that blew out of the big trash can behind the cafeteria, so I put it on my head like a…like a…” She turned to face her parents’ pew and cupped her hand around her mouth as she hollered, “Mommy, what was that thing Aunt Lily put on her head at her wedding called again?”

“A veil?” Fr. Tom suggested as Susie’s mom put her hand to her forehead and shook with laughter. Much of the congregation was reacting similarly. One fifth-grade boy in the back row laughed so hard he bumped his head on the back of the pew and had to be led out into the vestibule by his father, who checked to make sure his head wasn’t bleeding. It wasn’t.

“Yeah, a veil!” said Susie. “It had some ketchup on it.”

“Well, were there any witnesses at your wedding?” When Matt and Susie just looked at him confusedly, Fr. Tom tried again. “Was anyone else there?”

“I was!” Everyone looked around to see who had spoken. Six-year-old Lacey Parks stood up from the back pew, waving her hand. “I was there! It was a be-youtiful wedding. I gave them two sticks and a leaf as a gift. And I hope I get a thank-you note in my mailbox soon,” she added pointedly to Matt and Susie.

“Hi, Lacey!” hollered Susie, jumping up and down. Matt started waving so wildly that Fr. Tom thought his hand might fall off.

By now, most of the adults in the congregation were trying to prevent their chuckling from turning into full-blown laughter.

“Well, I’m glad you had a witness,” said Fr. Tom. “That does make it more official.” He thought for a moment, then asked, “Did a priest do the ceremony?”

“Uh-huh,” said Susie.

“Really?” Fr. Tom raised his eyebrows.

“Yep,” said Matt. “Evan Priest. But he doesn’t wanna be a priest when he grows up, even though it’s his name. He wants to be a vet.”

Fr. Tom chuckled. He couldn’t help it. “Well, that means your wedding was technically officiated by a Priest.”

“Yeah,” Susie said. “We learned about that in religion class.” She held up her left hand. “And see my ring? Matt made it for me in art. It even has a jewel on it!”

“So it does,” said Fr. Tom, smiling as he leaned over to examine the piece of purple paper wrapped around Susie’s fourth finger.

“The jewel is blue ’cause that’s my favorite color,” said Susie. “I drew a T-rex on Matt’s ring.”

Matt waved his hand around excitedly. Fr. Tom could just catch a glimpse of an orange piece of paper with a green, dino-looking shape on it.

“We know they’re not ’fficial,” Matt said as Susie nodded. “That’s for when you’re grown-ups.”

An older lady in the front pew wearing a stiff, knee-length maroon dress adjusted the hat atop her poufy white hair and muttered, “It won’t last.” The woman sitting next to her frowned as she whispered, “Mom, they’re little kids. Let them have their fun.”

Back in the Polska pew, while Fr. Tom asked the other three couples about their weddings, Matt’s dad whispered, “Matt got married? I’m sad I wasn’t invited. You two boys better invite me to your weddings, all right?”

His older sons rolled their eyes. “Sure dad, whatever.”

Across the church, Susie’s father was making a dad joke of his own: “Why wasn’t I asked to walk my daughter down the aisle? She’s my oldest, you know. Already married, I can’t believe it. Honey, did you have any idea?” Mr. Anton dabbed at imaginary tears with a tissue he’d found in his pocket.

“No, dear, I had no idea,” replied Mrs. Anton with a dry chuckle as she shifted her one-year-old daughter in her arms. “Now would you hand me that bottle, please?”

“Alrighty then,” Fr. Tom smiled. “Now that we’ve heard from everybody, please bow your heads for the blessing.” As the couples joined hands and bowed their heads, he picked up his prayer book and prayed, “Lord, please bless these couples that were married in the past, whether it was five or fifty years ago, and the ones to be married in the future. Help them to be faithful partners and companions in leading each other to holiness. In your name we pray, amen.” To the couples he added, “You may now seal this blessing with a kiss.” Whipping his head up to look at the kids, who he’d almost forgotten were there for a second, Fr. Tom was surprised to see Matt scrunch up his face and kiss Susie’s hand, which she held out to him tentatively with her eyes closed. The congregation had another good laugh as they clapped for the couples.

“After Mass that day,” Matt said, his eyes sparkling, “Susie’s mom came up to my mom and jokingly said that if their kids were going to get married they should probably get to know each other better. That Sunday was the beginning of a beautiful friendship between our families. We spent a lot of time together after that, and Susie and I became friends—good friends. Our families had picnics together in the spring, exchanged presents during Christmas break, and got together for supper often. We all took a vacation to Rome one summer, and Susie’s little sister, your Aunt Annie, was a flower girl at my oldest brother John’s wedding. You know, Lana and Ellie’s dad?”

His son and daughter nodded raptly from their beds on either side of where Matt sat, cross-legged, on the floor.

“Susie and I started dating during our senior year of high school,” he mused, “and when we got married after college, we gave each other real rings to replace the paper ones from first grade. Although they are similar—hers has a sapphire on it, and mine has part of a dinosaur bone that I found on my first archaeological dig. We got married in the same church where we’d had our marriage blessing back in the day, the same one where we go to Mass every Sunday. Fr. Tom was pretty surprised when we announced that we were engaged—for real this time—and asked him to officiate our wedding. He teased us a little bit, but was also our biggest supporter. He retired the year after that. And, well, that’s the story of how your mom and I got married.” Matt smiled at his son and daughter, who looked as if they’d just been taken on the rollercoaster ride of their lives.

“You mean you and Mommy knew each other when you were our age?!” Tommy asked incredulously.

“That’s right, son,” Matt laughed. “Your mom and I met when we were the same age that you and Julia are now.”

Susie peeked in through the open bedroom door and smiled at her husband and their six-year-old twins. “How was the story?” she asked.

“It was great, Mom! Really great!” they responded.

“Just fine, honey,” Matt said as he stood up to give his wife a kiss on the cheek. “How’s your story going?” The twins began bickering about whose stuffed animal was whose.

“Okay,” Susie shrugged. “I’d like to bounce some ideas off of you once these two are tucked in.” She gestured to their kids who were now tossing stuffed animals at each other from their beds on opposite sides of the room.

“Of course.” Matt put his arm around his her. “Would you be able to look over the grant proposal I wrote for the Thomson dig?”

“If I have time.” Susie sighed and leaned into her husband. “This manuscript is due tomorrow.”

Suddenly Julia glanced up. “Mom, did Dad really give you a paper ring?” she asked.

“Yeah,” said Tommy. “What happened to it?”

“Oh, I still have it. It’s in my jewelry box,” Susie replied.

“Really? Can I see it?”

“I’ll show it to you tomorrow, okay? For now, it’s time for you two to get some sleep,” Susie said. She and Matt leaned over to tuck their children in.

“Goodnight, kids! Sweet dreams!” said the parents who were once kids.

“Goodnight Mom! Goodnight Dad!” said the kids who would one day be parents.

Author’s Note: This story, like most of mine, is semi-autobiographical.

The description of the church is based on Saint Pius X Catholic Church (and school) in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where I grew up attending Mass every Sunday like Matt and Susie. And Father Tom in the story is honorarily named after Father Tom Hildebrand, who was the pastor of Saint Pius from 1996 until his death in 2004. Though I never met him, Saint Pius School established an award in his memory (it includes a $500 scholarship to Tulsa’s best Catholic high school), which I received when I graduated from eighth grade.

Saint Pius Church also offers marriage blessings once a month towards the end of Mass, with a similar setup to the one in the story (couples who celebrate their anniversary that month come to the front, the priest asks how long each couple has been married, and then says a prayer over them). But where the similarities to real life end, the story begins. In all my years attending Mass, I can honestly say that I’ve never witnessed a marriage blessing quite like Matt and Susie’s!

Ω

Sarah Ray is an English major at Tulsa Community College. She enjoys reading and writing, and has kept a journal on and off since the age of seven. She also recently discovered a passion for historical fashion, and (with a teacher's help) sewed her own medieval gown for the Renaissance Faire last year! Sarah hopes to work as an editor after graduating from TCC and getting her bachelor's degree.

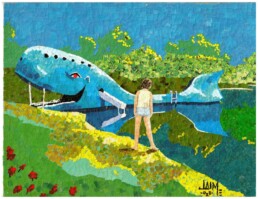

Jamie Cunningham is an accomplished artist in several mediums. "Reflections at the Pool of the Blue Whale" is part of a series of paper collages depicting cultural landmarks from Tulsa, Oklahoma, and surrounding areas.

My Brother’s Keeper

by MICHAEL CONNISTRACI

The landline in my father’s kitchen screamed like a siren. I brought the phone to my ear; I heard Steve’s voice.

“Whatcha doin?”

No hello. No how are you.

I tried to think quickly of an excuse not to see him.

“Come over to my apartment,” he said. “I want to show you something.”

I knew this was another of my brother’s lies.

It was 2005, and I was in my second year of graduate school in New York. I had been bartending full time at night while attending classes during the day for the past eighteen months. I had kept up the treadmill of work and study as my father’s health had steadily declined, his kidneys failing despite dialysis. He thought dialysis gave him a free pass to eat a bag of Milky Ways nightly. It hadn’t worked out that way. My father and siblings, Sandy and Steve, lived in San Jose. My professors gave me accommodation for two weeks, and I was able to fly back to California to split care for my father with my sister, Sandy. Steve was not up to caregiving duties.

Steve had told Sandy that he had moved in a 22-year-old heroin addict named Jerry so he could “sponsor him and straighten him out.” I knew that was a fairy tale; both of them were shooting up and splitting the rent.

I drove to Steve’s apartment. The grinding fatigue of caregiving and lack of sleep made my eye sockets burn and throb. I was the parent now, spending long, silent days bathing and feeding a father who beat his children for years before illness gradually made him an invalid. I felt cold inside as I parked the car and walked to Steve’s apartment. The apartment building was next to a 7-Eleven and a nail salon. The apartment was on the ground floor. I knocked on the door and Steve shouted for me to come in. The kitchen stove and backsplash were splattered with tomato sauce like the climax of a horror movie; the sink was piled with dishes and the counter edge had cigarette burns, probably from the smoker nodding out before the butt made it to the ashtray. The living room had four or five cardboard boxes with clothes, underwear, and socks hanging out of them.

Steve’s young roommate was passed out on the couch. He had on a Wilco T-shirt and Pokemon underwear over his thin, white body. The needle marks on his forearm looked like bee stings.

Steve and I walked out to his cinder block patio and sat at a metal table under a faded yellow cloth umbrella. I could see paint peeling off the fabric. Steve had put on weight—maybe twenty pounds. He had a pot belly, and his beard, always so neatly trimmed, was shaggy with food crumbs in the tangle of hair; his handsome face was spotted with blackhead pimples, a sure sign that he was shooting heroin.

“I’ve figured it out,” he said.

“What’s that?”

“My so-called illness, whatever you and Sandy call it,” he replied.

I was silent. I could only stare into his eyes. I didn’t have the will to argue.

He stared back, defiant.

“This is me. I am the energy; I am mania. I am humming with manic power. Manic is my essence. Manic is who I was born to be, who I always was. I lied to myself when I agreed to take the meds for nine years.”

He snuffed out a cigarette. The ashtray was brimming full; the old butts spilled onto the table. “You made me lie to myself, to my soul, to who I really am.”

I gazed at him for a silent minute and turned to stone. There was something so final in that remark that I realized the conversation was over.

“Well, good luck.” I moved to walk out to my car. “I hope things work out for you.”

“Wait a minute, what’s the rush?” he said. “I need to ask you something,”

I stared at him with no expression, knowing what was coming next.

“I’m a little short, Michaelo. Can you lend me a couple of hundred?” He gave me his best car salesman smile, the one he used when he was sure to close a car sale, back when he used to work.

Guilt, resentment, and an ache of longing moved through me. The years of hearing the same question and always opening my wallet, or my car, or my apartment, or my life to bail him out, just one more time, the this will be the last time, I promise, and then the last time just became the next time, and the next time, and the next time after that.

“I’m done, Steve,” I said. “You’re going to have to find another ATM.” I couldn’t feel anything as I said it. It was like hearing a stone drop in an empty well.

The slide into relapse and mania had come two years before. It erupted quickly. Steve had been sober and in recovery for nine years, and during those nine years, we had bonded more closely than we ever had before. I spent almost every weekend with him, helping him around his house, going to flea markets or having family dinners with his wife and daughter. Then he had a heart attack, and shortly after that, his wife told him she was leaving him for another man. He stopped going to meetings, stopped taking his bipolar medication, and began doing speedballs, a cocaine and heroin cocktail. The mania took over, and he never came down, his mind running one hundred miles an hour every day.

Along with my sister, I had spent most of my early adulthood bailing him out of jail, taking him to the ER, lending him money, and answering his 2 a.m. phone calls to discuss his grievances and resentments toward life in general. Now, twenty years later, my role as my brother’s keeper returned after I had thought I would never have to take on that responsibility again. I was in the middle of my own divorce and in graduate school to change careers. To take on being his savior felt like I was being pulled down into the ocean with an anchor tied to my feet. I couldn’t be the hero and save my brother again. I could barely save myself, but the pull to rescue him was so strong.

A few days after I walked out of his apartment, I returned to graduate school in New York.

Two weeks later, I was picking at a spinach salad and studying. When the phone rang, I looked at the clock. It was close to 10 p.m. I answered and all I could hear was Sandy crying and gasping for air, her voice strangled.

“Steve’s dead, he’s dead,” she wailed.

It felt like the floor had dropped. My head spun. I struggled to speak.

“How?” I mumbled.

“I don’t know, his heart—he was with that kid, Jerry—he just called and told me.”

I got his friend Jerry’s number and called. An older woman picked up the phone and got him on the phone, and I asked him what happened.

Jerry spoke in a torrent, “Mike, Mike, I swear to God man, he just died. My mom brought us some soup, and Steve said he didn’t feel well and went to lie down, and I went to check on him and he was dead.”

I suddenly flushed with rage.

“Don’t lie to me, you little fuck, you were shooting up and he OD’d, didn’t you?” I screamed into the phone. “That’s the way it went down!”

Jerry started crying on the phone.

“No Mike, I swear to God, we hadn’t used that day. He just ate the soup and lied down, and then he died.”

My breathing was ragged. I hung up the phone and sat frozen in place, staring out into space, for hours.

The autopsy said that Steve’s heart had blown up, enlarged on one side. He had gone into cardiac arrest. He was fifty-two years old.

We had him cremated, and my aunts and uncles came to my father’s house to tell stories of my legendary brother: so handsome, a man who could sell snow to Eskimos. A cousin told everyone that Steve was his role model for the man he dreamt of being, someone so charismatic he lit up a room when he walked in. I wrestled with this image of Steve, but could only remember him, dissipated and manic, under a faded, yellow umbrella.

We took Steve’s ashes and sprinkled them in the waters of Santa Cruz. We didn’t really know any other place he would think of as home, so we settled on the ocean. The day was overcast, and the water reflected gray; I waded out to my waist with a wreath of flowers, and a gust of wind blew the powdered ash onto the waves. A little wind and he was gone.

I dreamed of him incessantly for years. In the dreams I was always with him when he died. I was the one who killed him—repeatedly. In one dream, I was carrying him in my arms up a steep mountain trail to the top of ledge, a thin thread of river running miles below. I held him close, kissed his cheek and threw him over the edge, watching him fall and drift, like a leaf in strong winds. In later years, my wife would often wake me to stop me screaming in my sleep.

In my work as a therapist, I listen to my clients’ painful ambivalence about caring for but ultimately leaving a loved one, a lover, a parent, a child, whose choices in life have ripped their bond apart. They tell me of their gut-wrenching choice to abandon someone because they were themselves dying by inches trying to save them. I see my brother before me as they speak, so magnetic, so handsome, and jealousy stirs in me—jealousy that, in the end, the drugs and mania had become my brother’s keeper and had taken my place in his life. I loved him but I couldn’t save him. I live with an uneasy regret. My brother and I, at the same time, were drowning. I swam to shore.

Ω

Michael Cannistraci's essays have been published in Entropy Magazine, Briar Cliff Review, Ravensperch, Literary Medical Messenger, The Evening Street Review, Long Ridge Review, The Bangalore Review, The Dillydoun Review, Quibble, The Bryant Literary Review, and Glacial Hills Review.

Sal Daña is a gender-queer, 21st-Century Mexican surrealist painter based in the Americas. Informed by psychoanalytic theory, they are interested in painting as a sublimation behavior. The work often depicts dream-like scenes rooted in anxieties around climate and gender.

We Take Our Demons to the Park

by ALPIE LEIN | 3rd Place, student poetry contest

We take our demons to the park.

We let them play.

We show them off,

Like summer knees,

Romanticize the injuries,

Weave baskets with collected sympathies

To carry doctor’s notes of mental disabilities,

Weave wreaths with pity and peony

Over coffee, and cake, and phony

Compassion, to hang for décor

On our front door

For everyone to see.

I cannot bring my demon to the park.

On the see-saw he’s too heavy,

Breaks the swing set usually,

Eats up all the other demons,

Gulps them up, one by one

Until all of them are gone.

Always hungry for a void I cannot fill.

Then chews up the baskets, and wreaths.

“He’s unpleasant, and he reeks of death,”

They say, and leave, their demons close to their chest,

Groom and feed them over spouses,

Use them to excuse spilled wine on white blouses,

Ugly arguments in their stately houses.

I cannot bring my demon to the park.

I cannot bring him anywhere.

In my house in a corner in the dark

He glares at me and

He and I, we share a drink, but still

He’s hungry for a void I cannot fill.

Ω

Alpie Lein, a photographer from Berlin, was born in 1983 in Munich, Germany. Currently taking time off to finish her English degree at TCC, she writes short stories and poetry in her free time. She has self-published two specific treatment-related cookbooks as well as the book Young Widowing For Beginners in 2022.

Trey Burnette is a writer and photographer based in Palm Springs, California. His work has appeared in The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, NBC News, The Sun magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and various literary journals. He is a regular contributor to DAP Health magazine.

Purgatorio

by NICOLE FARMER

after Amanda Moore

I know nothing of knitting

but what I can braid together from

this yarn of yearning

& fashion some sort of hairshirt

to cover my broken chest.

The mountains surround my home

& my tortured dream bed where

my mind struggles to fix this fissure nightly.

Trucks race by my window.

Headlights transform blinds into bars on my walls.

The moon is a bright O of seduction.

She mesmerizes my sleepless hours.

Mysteries of my daughter bubble in my brain

like a cauldron of misunderstanding

an unravelling spool of heartstrings

& I miss her

& I miss her more.

I am the stranger.

My penance = waiting.

Ω

Nicole Farmer has published two books of poetry, Wet Underbelly Wind (Finishing Line Press 2022) and Honest Sonnets (Kelsay Books 2023). Her poems have been published in over forty magazines. She was awarded the first prize in prose poetry from Bacopa Literary Review in 2020. She lives in Asheville, NC. Find her at Farmerpoetry.com.

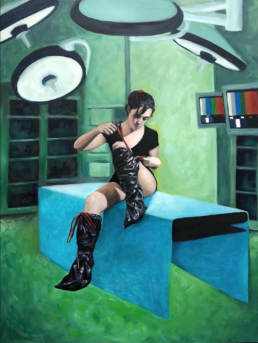

Jax Perry is a Boston-based artist who utilizes paint as a vehicle for storytelling, while often blurring the boundaries between realism and surrealism. Alongside her artistic pursuits, she works as a research lab manager in the division of Hematology and Oncology at Boston Children's Hospital and Harvard. Her paintings attempt to capture moments and weave a narrative.