The Bagboy

by TRACE CARSON

Standing in the breakfast foods aisle at the grocery store near your mother’s assisted living facility, you look for a box of original Cream of Wheat. Your mother has a small galley kitchen in her unit, and you try to keep it stocked, making trips like this once every two weeks. She doesn’t like to go to the facility’s dining room, although it’s available for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, so the caregiver fixes simple meals. The caregiver texts you when things begin to run low, and you keep a running list.

You eat every meal out and take the opportunity to pick up snacks for yourself. Several bags of salt and vinegar almonds, peanut butter that you’ll eat out of the jar, expensive blocks of cheese, maybe a container of hummus and bag of celery sticks. Just so you have something at home to snack on that doesn’t require dishes, an oven, or even a microwave.

“You idiot,” you say to yourself when you realize you’ve wasted time looking at rows of fleshy-faced Quaker men in white wigs instead of for the faces of smiling Black men in white chef hats. “What defect do I have that makes me unable to look?” You finally find the boxes of “original” between the boxes of “maple brown sugar” and “banana and cream.”

“Okay, do your sevens,” your mom says.

You’re lying on your back on the kitchen floor with your feet flat against the wall next to the pantry door. You scoot your butt to your heels and give a big push with both legs to see how far you can slide on the always clean, slick, shiny vinyl floor. Cool, you think to yourself as you break your old record. Mom is standing over the stove, cooking dinner. She’s making meatloaf, which is not one of your favorites.

The sevens and eights still trip you up, so you concentrate as you scoot your butt to your heels again.

“One times seven is seven; two times seven is fourteen; three times seven is twenty-one.” You get to the tricky part: “Seven times eight is fifty-eight; seven times nine is—”

“What’s seven times eight?”

“Fifty-six. I know that. Seven times nine is sixty-three…”

You know there’ll be a salad and, with meatloaf, mashed potatoes. And some sort of dessert. Homemade chocolate cake is usually on hand. She mixes instant coffee into the homemade icing and it’s delicious. You’ll eat the cake carefully, separating it from the icing, which you save for last. When you’re done the icing will stand firm in an “F,” and you’ll savor each chocolaty bite with the faint coffee taste. On the rare occasions when there’s no “ready” dessert, she makes milkshakes in the blender—chocolate for you and strawberry or vanilla for her.

You continue to scoot, slide, and recite your multiplication tables. Mrs. Butler has your fourth-grade class go to the twelves, which is impressive, you think, because at that point you’re hitting three-digit numbers. Your mom has omitted the ones, twos, fives, tens, and elevens from your nightly practice since they’re now too easy for you. You recite the elevens to yourself because you like the pattern. She opens the pantry door next to you, looking for something on the shelves.

“Go downstairs and get me some celery salt.” You continue to slide. “Now,” she says.

“Okaay-ya,” you say as you get up and trudge down the stairs to the basement.

Half of the basement is finished. You walk into the downstairs den with the brick fireplace that is never used except for your parents’ parties once or twice a year. This is the room where Dr. Moneymaker had the heart attack and died during the Christmas party last year. You walk through your playroom that your grandfather remodeled for you. The walls are wrapped in white paneling with baby-blue-highlighted fake wood grain. The eight-inch floor tiles are white with an embossed geometric design, also in a light blue. Built-in shelves and a long counter run along one side of the room. The room is packed with all sorts of toys, many that you don’t play with any longer. Some you never did.

You turn into the large, unfinished part of the basement with the hard slab floor where the furnace and water tank are hidden in shadow. This part of the basement smells different than the rest of the house. Your father’s desk, a hollow-core door painted in black lacquer, is supported by a two-drawer filing cabinet on either side and covered with stacks and stacks of paper. An old manual typewriter sits on a flimsy aluminum stand to the side. Metal shelves filled with notebooks separate his “office” from the mechanical stuff.

In front of his desk are two rows of two metal racks. Each rack is six feet long and has five shelves. You’re not tall enough to reach the top shelf yet. They’re stocked with non-perishables: cans upon cans, boxes of different mixes, flour, sugar, condiments, spices, pie tins, Saran Wrap, Reynolds Wrap, and Mason jars of tomatoes, pickles, and green beans that your mom canned. It looks like a mini-grocery store. A playmate once asked why there’s so much food. You shrugged your shoulders, never having thought about it before.

You look for celery salt. You know it’s going to be with the spices. You see the big, cylindrical, blue container of Morton’s Salt with the girl holding the yellow umbrella. You had asked your mother about the slogan, When it rains, it pours. She told you it means the salt won’t clump in humidity. You see the McCormick’s pepper in the red-and-white rectangular tin. You see Mrs. Dash’s lemon-pepper with the yellow cap that your mother loves to cook with in the more familiar-shaped spice bottle. You scan each of the glass containers, reading the names off. But you don’t see celery salt. A sense of dread overcomes you. You walk back upstairs, head low, knowing she’s going to send you down again.

“I can’t find it.”

“It’s on the third shelf along the back wall, the one in the corner,” she says with a sigh.

You go back down.

“Look, look,” you say to yourself.

You stand frozen, eyes glazed, looking from jar to jar. There’re dozens of them.

“Do you see it?” your mother says loudly. She’s in the kitchen, directly above your head.

“Not yet,” you yell back up.

“Keep looking.”

You stand. “Look!” you say to yourself over and over.

And then, as if with a divining rod, you slide two bottles of onion salt aside, certain to reveal the celery salt. Your heart sinks when you see it’s garlic powder. Then you notice it, staring right at you from the front row. Relief overwhelms you. You didn’t realize your body was so tense. You grab the bottle, and it falls on the concrete slab, unbroken. You take it upstairs.

“Thank you, honey,” your mom says as you hand it to her. “I knew you could find it.”

You’re checked out and leading the bagboy, who’s pushing the grocery cart, to your silver Audi. It’s a late-model, two-door, sporty thing in silver with a powerful engine. You don’t often have need for a car, but when you do, you want something fun and zippy to drive. The trip to your mother’s is not enjoyable with the traffic and congestion on 395. But on the occasions when you take scenic rides to clear your head, on open highways, your Audi makes you feel like you’re on the Autobahn. Shifting on the twists and turns up and down Skyline Drive, it’s as if you’re driving in Monaco’s Formula One race.

There’re not that many groceries, and you could carry them yourself, but the Mongoloid bagboy was determined. You’ve noticed that grocery stores have all but done away with the sensible paper bags with handles. What could have fit nicely into two paper bags are now in nine small plastic ones, some with just two items. You asked the bagboy—who is, in fact, an adult—for paper, but he’s talking about his favorite football team, the Patriots, and isn’t listening to you.

You realize “Mongoloid” and “bagboy” are both incorrect. “Person with Down syndrome” would be the politically correct phrase. Or is it? you wonder. Is that what we’re supposed to call them? Or just mentally challenged? Your daughters would tell you, but they haven’t spoken to you for three years. Only someone with his condition, you think, could get away with wearing a Brady jersey under his green, store-issued vest in a town of die-hard Redskin fans, no matter what their record. Then you think about all the hoopla around the name “Redskins.” That’ll change one day soon. Your mind wanders, and you ponder “bagboy” versus “bagman.” Bagman connotes something completely different. Why the fuck am I thinking about this crap?

So, against your better judgement, you lead the mentally challenged bagman, with your nine small plastic bags, to your car. You pop the trunk and he begins to unload them, two at a time. With each flimsy, formless bag he puts down, items spill out. As you put a pint of Half-and-Half back into a bag and loop the top in a knot, he drops the bag with the carton of eggs onto the asphalt. Globs of yellow-golden yolk ooze between the two halves of the carton, which landed upside down but managed not to open.

“Goddamnit!” you utter under your breath.

“U’m sawwy, u’m sawwy,” the bagboy says as he scoops up yolk with his hands. There’s yolk on the can of green beans, the only other item in the bag.

Ω

Trace Carson was born in Washington, D.C., and grew up in Arlington, Virginia. He received an undergraduate degree in business from the University of Virginia. He enjoys oil painting—landscapes and abstracts—and during Covid enrolled in three semesters of an online fiction writing class through the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, where he experimented with short stories. He has lived in Richmond, Virginia, for 35 years, and has two adult daughters, one of whom recently published a book of poetry.

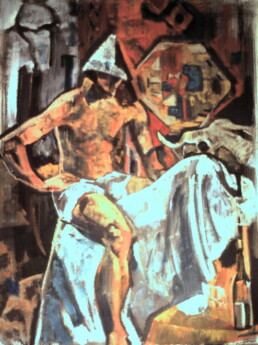

Renee Samuels was born in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, and grew up in Waltham, Massachusetts. After studying English literature, communications, and art at Boston University, Samuels moved to Woodstock, New York, in 1987, and studied drawing, painting, and art history with Nicholas Buhalis for five years. Samuels has exhibited her paintings, drawings, prints and collages since 1988 in solo and group shows in the Hudson Valley, New York City, Albany and Cambridge, Massachusetts. Aside from making art, Samuels enjoy bike-riding, walking, reading, and Cape Cod.