The Nun of Melba Toast

by ELEANOR LEVINE

There are many fine moments in history: the post-Cold war period, the pre-Enlightenment era, and the Weimar era. I’m entering the post-Cholesterol Enlightenment era. I am learning there are great things to eat that are healthy: strawberries, peppers, cherries, peaches…also: edamame, seaweed…translucent low cholesterol…green and see through but comparable to algae, which, I’ve heard, is tasteless. Whether it is avocado or gluten-free Trump cupcakes, there is always a need for a meatier, finer substitute that transforms me from fat and indolent to youthful and spunky.

No one would know from my fat-cell indulgences as an adult that I once had a lithe figure—in my teens. I don’t know if it was high metabolism or my mom’s semi-bad cooking or my dad’s obsession with high-cholesterol products (he had a heart bypass and an existential crisis about fried eggs, though he cooked them), but it was not until I left the fold—the suburban-assimilated ranch along the highway (where Hasidic school girls now dance in delight in a building that has replaced what was once my house)—that I began to consume melted cheese and French fries and pizza.

My parents could not afford and/or allow us to order pizza or fries. No, we were a family that disavowed the notion of gratuitous eating that would later lead to a triple bypass, or the heart attack that was a result of a bag of Cheetos.

We had family issues around eating. Particularly my father. I suppose it was not the unhealthy things that threw him into a rage. He was used to that, and few of us deterred from our parents’ resolve not to bring junk food or butter or ice cream into the house—unless it was the rare occasion that we received an A- in algebra, when we celebrated with indulgent, high-cholesterol products such as Ben & Jerry’s. My father was mostly pissed if we tried something radically different, such as transforming into a vegetarian. Having grown up in the 1930s Depression era, Dad’s diet philosophy was, “If we have it, you’ll eat it.”

We were mostly like canines in our house, searching for the item that was indispensably bad for us, whether that be cheesecake or cheeseburger, which was not an option, because we were ostensibly kosher, not counting the times my mother brought shrimp with lobster into the house, or those intermittent occasions where no one mentioned the food’s heathen-like qualities and we ate unkosher products on paper plates. That occasional moment would have been okay if we did not also ruin my mother’s extensive silverware collection with goyisha ingredients that no Hasidic Jew would ever embrace—even on a molecular level.

So, it behooves me to say, that, at the Zionist socialist summer camp, where my parents sent me and my brothers, I was inveigled with people from all over the tristate area who dabbled in culinary digressions such as making fresh bread, eating tofu, generating cholesterol with gourmet ice cream, frying zucchini with mozzarella cheese and garlic, and serving pork substitutes. What really fascinated these fellow Zionists, some from a higher socioeconomic level than my own—in that their kitchens were displayed in elite architectural journals—was their fascination with food choices that diverted from the mainstream, middle class. You know, as my father would say, “things that wasted our money.” Thus, against my better judgment, and knowing full well it would cause my father cardiac arrest, I became a vegetarian.

In truth, the real motivation for becoming a veggie, though it was a short period in my not-so-long life (I was only sixteen), was that I liked Hildegaard, a trans girl at summer camp who did not know she was trans. She, like me, wanted to be a boy and easily dressed like one without much effort.

I strove to elicit low decibels with my deeper voice; I was smelly and klutzy and embraced nonfemale virtues that more resembled Charlie Brown than Lucy. I was not exactly Pig Pen. I was a higher echelon—above Pig Pen. Several inches higher than him (I am assuming this was his correct pronoun). I smelled and offered dirt enzymes to others for free, and the girls threw negative adjectives in my direction. Some even put a maggot or two (from the chicken shit on our camp kibbutz) on my bed. The worst was when they put a dead mouse on me when I slept, and I cringed more with embarrassment than fear.

Hildegaard, my veggie/crush/mentor, was quite popular, and when the other girls were outside or doing avodah (means “work” in Hebrew), Hildegaard talked with me, flirted, and joked about my disheveled manner.

“You are an adorable mess,” she said.

“Huh?”

“Well, my parents would never tolerate that drek on your bed.”

Hildegaard was blonde with hints of frost, but young enough where it looked completely natural.

“You’re a veggie?”

“Huh?”

“Are you a vegetarian?”

“No, are you?” I didn’t know her cuisine status initially because I was not permitted to sit with her. It’s like this with my love interests—they need to be haughty and unapproachable for me to like them. I normally sit with social-outcast girls with greasy hair and incoherent thoughts about NASCAR. We are all alone, while the girls at the neighboring table giggle over organic meals.

Hildegaard was closeted about her friendship with me, though it had a slightly romantic element; not being open about it preserved its mysterious and addictive nature. Hildegaard would stand a few feet from me—sneak a peek or give a blink—while we sang the proletariat song before entering the dining hall.

“Yes… you should try it,” she’d whisper about eating fewer mammals. “Get the lentils and tofu.”

Of course, it was trés difficile to change one’s diet at summer camp. You had to say you were a vegetarian at the beginning of camp, like asking for kosher meals in prison. Notification allowed the “authorities” to grant you esoteric food choices. I remained on a diet of mostly mashed potatoes, chicken, and green beans with an occasional hamburger.

Hildegaard, who was taller than me and a devoted athlete and noted scholar in an upstate New York private school, had a “crush” effect on me. The “crush” effect is when I fantasize about a relationship that does not exist.

In my brain we were sitting in a barn where she’d kiss me, though I envisioned she had another girlfriend. Not me. I was a flighty nerd who preferred non-Lauren shirts. Her chick was a refined preppy him. They both subscribed to The New Republic while I occasionally read Pauline Kael’s movie reviews from my dad’s New Yorker. They dissected flies. They hunted for rare mosquitoes. I picked jam from the jar or killed spiders. Hildegaard and her “friend” were on the debate team, whereas I was on the forensics team, and read the lyrics of Barbra Streisand at public speaking tournaments throughout New Jersey.

Thus, since this love affair only existed in my cerebrum, during and after I left camp, I became a veggie. I’d pay tribute to Hildegaard, extend the liaison (that did not exist) (except in my head) to the fresh produce at the local farmer’s market. A prolonged meditation on nonexistent poontang became the resolute worshipping of fried mushrooms and tomatoes. That was my religious altar. My vegetarian/Buddhist shrine to the Goddess of the Zionist-socialist camp: Hildegaard with blonde hair and pedigree green toenails that symbolized her spiritual attachment to all things green and down-to-earth and purchased at Anthropologie®.

Hildegard’s father was a veterinarian and an academic. Mine was a high school social studies teacher. My dad made less money, though he had studied at Columbia University’s Teachers College. (They didn’t let poor Hebrews into Columbia College in the 1940s, but Teachers College approved of lower-income Jews unable to pay for a chair in communications.) That my dad was a semi-member of the Ivy League—this was something I let people know, though our fragmented economic status did not endear me to people at the socialist camp or their relatives who raised money for the homeless and were photographed in the society pages of The New York Times. Indeed, if you were going to be a prole, you need to dress like one intentionally; these scrappy kids had an entirely upper-class ability to look impoverished.

It would have grossed them out that Stalin’s dad made shoes or that Stalin was mostly poor until he started killing his opponents.

Even Trotsky—who is riveting to socialist Jews from the Upper West Side—came from humble beginnings. His dad, I believe, was a farmer subsidized by the Russian government. Daddy Trotsky would not, in his odorous overalls, have ordered a sesame bagel with whitefish salad at Zabar’s.

After a month at camp—which was financed by a scholarship from my mother’s boss—I went home to Dad’s kitchen, with his Tupperware containers and canned vegetables and corn meal that we boiled and ate with sour cream and cottage cheese. Not like the wealthy chicks who ate mint leaves in their tea while posing with their dads in Bermuda. My father, who taught history during the year, was off in the summer and our chef in the kitchen (while Mom worked), though he was limited in his cooking skills—eggs and sandwiches. He also did a good pot of Campbell’s Tomato & Rice Soup and a superb Kraft Mac & Cheese. Whatever might be on sale at ShopRite.

“Daddy,” I said to him as he fried his eggs with loose yolks. “I can’t eat these dead birds.”

“What?”

“I am not going to eat the aborted fetuses of chickens.”

My father, who is normally even keeled (unless you eat before dinner and ruin your appetite), was not happy.

“You can’t be a vegetarian,” he said.

“Hildegaard is,” I said, thinking of her light ringlets and unshaved calves.

“Who the fuck is Hildegaard?” he asked.

“She’s my friend.”

In the seventies, in our house anyway, you didn’t want to tell your dad that you, a yet-unknown trans girl/guy, had a crush on another trans girl/guy/they who didn’t eat meat. Though my dad was a Roosevelt Democrat during the Depression era who wrote an anti-Vietnam War letter to the local paper (that almost got him fired), he could not conceive of the trans concept or the fusion concept or that pronouns would multiply, in forty years, like baby cockroaches. And the veggie shit, as stated earlier, was also too much for him.

“Why doesn’t she eat meat? I mean eggs?” my father asked.

“She thinks we are eating flesh and the baby of flesh.”

“Is Hildegaard a Roman Catholic?”

“No—a socialist from Poughkeepsie. Her dad is a professor at Vassar.”

“I don’t give a shit if he’s in charge of the New York Stock Exchange,” Daddy said, while my impudent brothers, whom I rarely spoke with (unless we were fighting) giggled in the background. They were younger and hostile toward me.

“Susan is not really a veggie, Dad,” one of my non-evolved siblings uttered.

“Mind your fucking business,” I roared. Being a foot taller always had an intimidating effect upon them and I shut them up before an argument or tangent flourished out of control.

“It’s really silly that you, who consumes more animals than anyone else in this house, suddenly prefers celery!” Daddy slammed the plate down. “Eat your eggs!”

I left the room.

About an hour later I snuck cottage cheese from the fridge.

A week thereafter I let him make me eggs. He fried the yolks. Made them firmer than usual. Put a little ketchup on the side, which disgusted me. Indeed, this was largely because my Hildegaard obsession flattened out. No internet or technology to stalk properly then and her phone number was unlisted.

Daddy was no Hildegaard. He was also not the current me with the indefatigable ability of non-stop inhaling whatever will terminate my existence at sixty-two. I am on borrowed time now, my friends tell me, because I chew food more than I ride the bike. And it is beyond the precipice of preventing a future stroke or heart attack, for I have been consuming a box of pizza every two days for more than forty years. If I had somehow mastered the Dad or Hildegaard School of Eating, I would not be in this post-apocalyptic predicament of over consumption.

My adulthood is the frying of cholesterol, and clearly, of course, the post-Cholesterol Enlightenment era where I should be eating tofu with hummus. My true nature, however, is gluttony. I would eat a dead platypus if I could sprinkle it with parmesan cheese. I love layers of sour cream in my vegetarian chili. I eat ricotta cheesecake like some might slurp spinach smoothies. I don’t do microscopic anything. I’m the antithesis of my once-thin body, where I would ignore obesity as you might a bad TV show.

But alas, I can no longer fixate on food as a religion. It must be as banal as walking your dog. Nothing dramatic will occur. My arteries will become less clogged and my soul less gluttonous if I dine on emblematic nothingness. Somewhere between veggies and egg yolks and Fried Oreos, I must rise from this dungeon of digestive chaos to be ninety-one, though I will be eating only Melba Toast. They will call me the Nun of Melba Toast. And I will shuffle my legs to the gym parking lot where I will quietly drive to a pizzeria and consume salads (not pasta) and live a proper few decades. I will have outlived my dogs, brothers, and parents, but be asexual, though not by choice. At least the Melba Toast—not the Fried Oreos from the Point Pleasant, New Jersey, boardwalk—will keep me fragile and thin. I will be like the dry-throated Labrador Retriever who wants ice cream but must settle for the brittle food in his dish.

Ω

Eleanor Levine’s writing has appeared in more than 150 publications, including The Hollins Critic, Gertrude, Raleigh Review, Notre Dame Review, Fiction, Faultline, and others. Her poetry collection, Waitress at the Red Moon Pizzeria, was published by Unsolicited Press (Portland, Oregon). Her short story collection, Kissing a Tree Surgeon, was published by Guernica Editions (Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

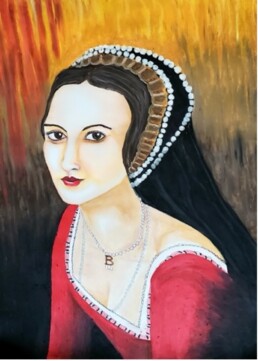

Sarah Jane Walker was born in Jacksonville, Florida and attended the University of North Florida, where she received a BA in Psychology in 2017. Her body of work usually conveys a story or an expression of a specific mood. With an obsession of English history, much of her work also portrays life in England’s past. She currently resides in South Carolina with her two kids.