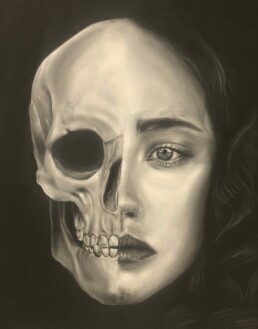

The Time I Lost Myself

by MELYSSA LIRA | Honorable Mention, student prose contest

I walk into the cold sterile building, my mind going in a million directions. I’m the youngest patient here, where the air is heavy with sorrow, trepidation, and differing levels of infirmity. I’m ushered to the right and through a set of doors to the room where radiation will be blasted through my lower torso by a large, mechanical beast that orbits my body as I lay on a frigid table five feet in the air. Thanks to Covid, I’m starting treatment alone for the cancer that is growing faster than my children did inside my body. My husband, Giovani, sits in the car praying I will be alright. He’s putting on a brave face like a Mayan warrior about to go into battle, but I feel his nervousness and fear that is matching my own. We have asked all the right questions that you’re supposed to ask but have gotten half answers. The doctors say things like “should,” “hopefully,” and “if.” We have a plan: Monday through Friday is radiation at nine a.m. for thirty minutes with chemo every Friday for six hours after radiation. Eight weeks. It doesn’t seem like an insane amount of time.

At the end of week one I walk into the building and turn right then continue through to radiation; after that I go up the elevator to the left where I will sit, uncomfortably, for the next six hours for chemo. I am alone surrounded by a field of reclining chairs filled with the shells of humans hooked up to an icy IV; the taste of chemicals invading my mouth. My body is starting to feel as if I have sat in the sun, with navel to thigh bare, long enough to have developed a sunburn. I remembered to ask all the questions that I could think of; again because of Covid I wasn’t able to have the “teaching class” where they explain everything to you before you start treatment. When I get home, I feel ok, I guess. I feel a slight tingling all over my body, like static electricity running through my veins. Then the nausea hits me with the force of a Mac truck. The doctors have prescribed me what I can only describe as the Rolls Royce of pain and anti-nausea medications, and like an idiot I didn’t listen when they told me to start taking them before treatment today. (I hate taking medication.) As I lay there praying for the pills to kick in, I start to feel my mind becoming murky and distorted. I’m slipping deep into an ocean of blackness that is pain and nausea, where little bursts of pictures flash by me. I see Giovani’s face hiding a grimace with a smile as he hands me something and then it fades. I see the nurses and technicians talking to me. I can’t make out exactly what they are saying, and then it fades.

I can’t think, and my memory doesn’t seem to be working very well either. I don’t know what day it is or when the last time I saw my children was. My son, Noah’s, face swims in front of me set in a constant state of panic and fear; my daughter, Caleigh, cries because she doesn’t understand why mommy can’t cuddle and play with her like she used to. I cannot remember when the last time I told them I loved them was. At this point I have no clue what week it is or how many treatments I have had. I’m beginning to feel like everything is happening to me and not with me; I am so powerless, and I hate it. There is a constant struggle inside my body between red hot searing pain from the radiation burns that have transformed my skin into bubbling, seeping patches of flesh and nausea so horrible and intense that all I can do is curl into a tight ball. All that the medication seems to be doing is slightly dulling my senses. I am granted minute respites from being thrown about in this black sea of Oxycodone, Morphine, and Zofran: in the mornings right before radiation treatments, and on chemo days when they pump me full of steroids to try to get me to eat. I quickly come to realize that these times are my lifelines, and I grasp at them like a sailor grasping at a life preserver after he has been flung overboard into one-hundred-foot waves.

I am now about fifteen radiation and three chemo treatments into the plan given to me by the doctors. Giovani has started to keep a running list in his phone of things that he thinks should be mentioned to or asked of the doctors, and he suggests that I do the same. He knows how much I’m struggling to remember even the big details amid everything I have been experiencing. So, I make lists and write everything down (or rather type everything out). I make lists of the things I want to say. Tell Giovani I appreciate everything he’s doing, that he’s doing great with distanced learning, and I love him. Tell Noah it’s going to be ok, that I will be alright, and I love him. Tell Caleigh I miss cuddling, too, that I’m sorry I don’t know how to explain all this to her, and I love her. I make lists of questions and side effects I need to mention and discuss with my care team. Why aren’t the handfuls of pain and anti-nausea pills plus the topical creams that I have been taking every couple of hours really working? Why do the medications only scratch the surface? Why do I need another blood transfusion? I am a knight battling a ferocious dragon, and my lists are my sword and shield. When talking to anyone and everyone, I furiously type to make sure that even the smallest detail is accounted for. Little by little, piece by tiny piece, I am slowly able to take back fractions of myself. The pain and anguish are a constant bombardment, but I am not as lost, not as unaware of the things around me, and not as unavailable to my family.

The next few weeks seem to pass by in a whirlwind of treatments, transfusions, and doctors’ visits; I’m sure it’s partially because of the amount of sleep I am getting, thanks to all the medications and how broken my body has become. The routine is for the most part the same, with the only difference being the switch from external to internal radiation (two words: reverse childbirth). I am constantly armed with my lists to make sure I am being heard by those around me. “Write that down,” is now a lighthearted joke directed at me by nurses, doctors, and my family alike. I am just glad to be able to have something to joke about again. The pain and nausea are repeatedly getting worse, so I have been given more medications. At least now I feel like I have a compass to navigate through these rough waters.

I hobble into the building that has become my second home. I still feel the fear and sadness pressing in on me; however, I notice something more—hope. My mind is clear except for one thought: hopefully it’s over. I finish my routine of taking a right down the hallway then through the doors that lead through to the radiation room. Four blood transfusions, six weeks of chemo, thirty external, and five internal radiation treatments has left my body fatigued, seared, feeble, and gaunt. As I come out from my last treatment, I see my husband and children standing outside the windows, with sunny flowers and a bright rainbow of balloons in hand. My husband’s face shines with a smile only great hardship can produce. He’s battered and bruised as I am, but his wounds are mental. My son is smiling but it’s guarded. He’s not sure if it is ok to stop being afraid for me. My daughter is just excited to see balloons, not fully aware of what’s been happening, only knowing that mommy has been sick. I step forward, running my hand reverently along the multicolored ribbons with messages of strength, hope, and love scrawled upon them by other survivors. How had I not seen these before? I reach out and clasp the string attached to the large bell on the wall, next to the ribbons, and pull hard. The sound that rings out and the cheers from the staff fill me with so much emotion that I am almost crushed by the weight of it. As I turn to look at my husband through the window, I feel his hope that matches mine;,and we just smile at each other. I’ve been told that there will be some lasting side effects, some could affect my short-term memory, but I will not lose myself again—not ever.

Ω

Melyssa Lira grew up in California, where her high school English teacher, Mr. Medders, encouraged and eventually instilled in her a love of writing. That love helped her through difficult times in her life by giving her a creative outlet to express what she was going through. In 2010 Melyssa moved to Oklahoma, where she married her best friend, Giovani. The pair have two children together, Noah (14) and Caleigh (7). In 2020 she was diagnosed with cancer but is, thankfully, in remission.