A Better Place

by JAMIE CUNNINGHAM | 2nd Place, student prose contest

Anna May was the eldest member of the little Cherokee community called Pin Oak and was something of a spiritual leader to those in the neighborhood. She was known as Pin Oak’s Beloved Woman, a position of respect. A position Anna May relished ever since her older cousin, Lucy Buck, succumbed to stomach cancer five years ago and the honorific fell to Anna. As Beloved Woman she was often the center of attention during holidays when everyone migrated to her house for Christmas breakfast or Independence Day cookouts. At such events, Anna’s exquisite frybread was usually the centerpiece. In addition, as eldest of the elders, she was often consulted in the domestic affairs of her neighbors which fed her girlish obsession for gossip.

They found Anna May after the quarantine. After no one had heard from her for almost three days. They found her on the kitchen floor barely conscious and talking in a soft voice, though she was mostly incoherent. Someone said it sounded like she was praying. Someone else said it sounded like a cooking recipe. The EMTs, both yonega —white folk—mistook Anna’s lilting Cherokee as the gibberish of a dying old woman.

It was Tina’s boy Charles, the husky one, who found Anna May that day. Charles—the kids all called him Roundboy—was notorious for showing up unannounced and uninvited wherever he thought a meal might be found. His poor mother did her best to keep him fed at home, but Roundboy’s stomach was seemingly boundless, so he often spent time after school roaming around Pin Oak looking for snacks. While other kids played tag or hide-n-seek, Roundboy foraged through his neighbor’s cupboards. Over time, the boy’s behavior, cute and endearing when he was five, had become a way of life for those in Pin Oak. At least he wasn’t a finicky eater and was easily satisfied with a plain bologna sandwich. It was Roundboy’s appetite that lead him to Anna May’s that fateful day, hoping for a piece of her famous frybread.

Roundboy grew up with Anna May’s cooking and knew she always kept a basket of bread on her stove, just in case of unexpected visitors. Among those of Anna’s generation it was customary to offer food to anyone who entered the home. Whether a pauper or the President, if you entered Anna May’s house, you were expected to partake in whatever tasty morsels she might have available. Even the meter man knew this custom well and scheduled his visits to Anna’s house just in time for lunch. It was considered a great insult to decline such an offer. But on that unfortunate day after the lockdown, Roundboy was distraught to find no frybread on the stove and Anna May crumpled on the kitchen linoleum.

Due to the pandemic, the funeral for Pin Oak’s late Beloved Woman was not as grand as Anna May would have hoped for, but it still violated CDC recommendations for such gatherings, which would have delighted the mischievous old woman. As tradition dictated, her body was presented in the living room of her home so family and friends could pay their respects, swap stories, and eat. In better times this celebratory wake might last for three days, but due to travel restrictions the reception was smaller than expected. The funeral home picked up Anna after just a day. The funeral was held graveside so the attendees could distance themselves if they wanted. Some did, maintaining six feet of space. It did not go unnoticed to the Pin Oak mourners that they were six feet above their ancestors, as well.

The eulogy, and even much of the service, was held in the Cherokee tongue. As the preacher spoke in his soft, stilted English, a dialect common among the dwindling elders, the old ones nodded stoically as the younger generation listened with reverence. Anna May’s nieces sang ‘Amazing Grace’ in Cherokee; the syllables memorized because they do not speak the language of their people.

Once Anna May was lowered into the ground, a procession of mourners lined up to toss a handful of dirt into the hole. Nearby, a county worker sat on a backhoe waiting to finish the job. As the bereaved made their way past the family members seated near the grave, they paused to shake hands and offer condolences. At the end of the row was Anna May’s younger sister Nan who bore her grief in silence, nodding to the well-wishers as they passed by. After everyone left, Nan remained, alone, staring at the treetops and reflecting on life. Her big sister was gone. Somehow, this fact both frightened and comforted her. One thing on Nan’s mind was, who would she talk Cherokee with now? When she finally rose from her chair, she heard the backhoe fire up. She gave the gravedigger a little wave, and he nodded back in obeisance. Now, Nan was Beloved Woman.

One the day the ambulance came for Anna May, Nan had been out in her garden. She heard the sirens fade and crescendo in the distance as the first responders weaved through the valleys along roads that twisted like ribbons of asphalt. Pin Oak is tucked into the woody Ozark foothills near the Oklahoma/Arkansas border. Approaching emergency vehicles can be heard for miles before they’re ever seen. Tina, who lived next door to Nan, came running over when she heard the dire news, and the pair waited nervously amid the tomato plants for the ambulance to arrive. When the orange and white van entered Pin Oak it shut off its alarms and rolled silently through the neighborhood as the curious peeked out their windows, holding their breath and wondering who was hurt or sick or in distress. Soon after, Roundboy came huffing and puffing up the road with a scared look in his eyes. In Nan’s garden he updated the women on Anna May’s condition, clinging to Tina like a toddler. Nan gave him a cucumber to chew on so he would calm down.

As the ambulance was leaving, Nan flagged them down. One of the EMTs recognized Nan and paused so the two women could talk. Nan, still nimble in her late-sixties, hopped up into the back and grabbed Anna’s bony hand. Anna, more lucid than before, smiled to her sister and motioned for her to come closer. Obediently, Nan laid her head on her big sister’s shoulder just as she did when they were little girls.

“Sister, are you okay?” Nan asked.

In Cherokee, Anna May whispered a touching elegy, ending with this declaration: “Dvganigisi”—I’m going home.

Nan had Tina drive her to the Indian hospital in Tahlequah, and later that night Anna passed away quietly and peacefully; not from any virus, but from an embolism, something no quarantine could keep out. Out in the cold hospital waiting room, Nan wept quietly. Though surrounded by her children she suddenly felt alone. She wanted to tell them what Anna May had whispered to her, Anna’s last words, but no one would understand. Though they were her family, they cried in English. When Nan grieved, it was in her mother’s tongue.

For the week following the funeral, Nan spent her days in her garden, a simple plot bound by a wire fence meant to keep out the deer and other critters. She busied herself by pulling weeds, shooing away blackbirds, and bickering with the rabbits. From the kitchen window Tina kept a wary eye on the elder woman and worried about her. Nan took Anna’s passing with enduring grace, but Tina was certain Nan must be breaking inside. Several times a day she called to see if Nan needed anything. She never did.

One morning Nan was in the garden when she received a visit from John, the best friend of her son Tommy. As teens the two boys were inseparable, chasing girls, drinking beer, and playing music; Tommy played the drums and John the guitar. As the boys transitioned into men, they began to spend more time playing the radio than their instruments. Sadly, Tommy died five years earlier, either from the diabetes or the booze, depending on who you asked. Since then, John had become a regular at Nan’s dinner table. To her, he was another son.

“Osiyo,” John greeted her as he came through the squeaky metal gate.

“Siyo, chooch.” She was sitting in the shade of a nearby oak with her paisley-patterned garden gloves folded on one knee. Nan smiled and brushed some dirt from her pants then pointed to some plants. “Those t’matoes are gettin’ kinda weedy.”

That was how Nan was. She would never outright ask you to do something. Instead, she simply pointed out a thing that need to be done, and it was implied that it was the responsibility of whomever was within earshot to get it done. John was half Cherokee himself, his long deceased mother a full-blood, so he was familiar with this peculiar tactic. It was a tradition of sorts that he’d failed to pass down to his own son. Maybe it only worked for mothers. John smiled and made his way toward the offending vegetation.

“Where you been, stranger?” Nan asked as she fished a saltshaker from her pocket. John had been noticeably absent since the pandemic began.

“Stuck in quarantine with a gal in Tulsa,” he said while tugging at a stubborn weed. “She had a nice kitchen, but she couldn’t cook. Sorry I missed Anna May’s funeral.”

“Osi,” she said with a little wave. It’s okay. “Sister didn’t notice. Funerals are so boring anyway. You hungry? There’s some eggs and frybread from breakfast on the stove.”

“I stopped at McDonald’s.”

Nan frowned at the notion of fast-food, then looked around her garden. “I need a couple good cucumbers, two t’matoes, and some lettuce if the rabbits haven’t chewed it all.”

John turned to inspect the produce. He chose two plump heirlooms and some fat cucumbers. Luckily the rabbits had left enough lettuce to fill Nan’s little wicker basket. Satisfied, Nan gathered up the bounty and started toward the house without a word. John followed. He knew better than to turn aside Nan’s implicit offer of food.

Nan’s kitchen always smelled like home to John. Decades of rich aromatic cooking had steeped into the wood of the cabinets and the piquant scent of frying oil and earthy spices hung in the air like a specter of meals past. It reminded John of his own mother’s kitchen. She had died soon after he graduated high school, and most of his memories of her were dominated by her stalwart cooking. It didn’t take a pop-psychologist to understand his fondness for Nan. John was forty-five now, and Nan had been a part of his life for as long as his real mother had been.

Nan began to wash the vegetables in the sink. She took a moment to look out the window and wondered where Roundboy might be. Nan secretly called the boy Ogan which meant groundhog. Nan had names for everyone in Pin Oak. Most of the names she kept to herself—especially the names she had for the white people living on the hill. Not that she was prejudiced, not really, but the yonega were mostly outsiders, young people with no ties to the community who tended to keep to themselves. The yonega didn’t go to the Pin Oak Baptist Church. They didn’t fish or hunt crawdads down in Cedar Creek. They didn’t play softball or Indian marbles on the community ballfield in the summer. They had no concept of Pin Oak’s Cherokee customs. In Nan’s suspicious mind, the yonega were hiding in their dirty trailers, cooking meth and watching reality TV.

“I heard there was a wake at Anna’s house,” John said as he chose a piece of bread from a basket on the oven. “I haven’t been to one of those since I was a kid.”

“Your mama didn’t have one?” Nan quizzed. Growing up, Nan had been to plenty of home funerals. These days, though, it was a dying tradition. One of many.

“No.” He pulled the bread apart. “I remember going to my Uncle Bird’s wake. I was about four or five. I walked into his living room and there was Bird, stretched out like he was taking a nap. Everyone was sitting around eating and telling stories like it was Thanksgiving. No one warned me there would be a dead body just parked in the corner like furniture. Freaked me out.”

Nan chuckled. “I guess not too many people do that stuff anymore. You know, the funeral director told me Sister was in a better place. Why are white folks always lookin’ for a better place?”

“It’s just something they’re supposed to say.”

“People been coming to this land for five hundred years looking for a better place—still ain’t found it. Well, if there is a better place, what are we doing here?” she sniffed, a clear signal that the subject was now put to rest. “So, how’s the bread?”

“The bread?” John raised his brows. “Fine, Nan.”

She shrugged. Anna May’s frybread was always better than Nan’s, and Nan acknowledged this without spite. Anna had always been the better cook which was just fine with Nan. Nan was the better gardener. But now Sister was gone and Nan was Beloved Woman. She guessed Roundboy would be coming to her for frybread now.

The sisters were born and raised in Pin Oak, never living anywhere else, although Nan once went to Washington, D.C. when her youngest daughter won some kind of school award. Because of that trip Nan had always felt a little more worldly-wise than her big sister. But times sure were changing fast. Anna and Nan were the last of their generation. As the old ones disappeared, so too did their culture. The kids these days were digital and their parents drove electric cars. No one had time for the old ways anymore.

“How’s your boy?” Nan asked as she shook the water from the lettuce.

“Osda,” John smiled. Good. “He’s working on the road. Making money. Found himself a good woman.”

“When you gonna find a good one?”

“I find a good one all the time.” He gave a rakish smile. “But they keep finding out about each other.”

“You and Tommy were just alike,” she laughed. She put the lettuce in a bowl then began to slice the tomatoes and cucumbers. “Always chasing girls.”

“Tommy didn’t have to chase them.”

Nan’s smile was wistful. Her son always had a way with the ladies. “We’ll need some plates,” she said.

John retrieved a couple of colorful plates decorated with chickens. Nan brought over the salad fixings then took her usual seat at the little round dining table. John made his salad. Nan said a quick prayer and they began to settle into their lunch. They ate without talking; the only sounds heard were their chewing and the hum of the refrigerator. When they were done, John cleared the table, dumping the plates in the sink. As he ran the dishwater, he leaned against the counter with his arms crossed.

“Kawi-tsu tsaduliha?” he asked.

“Vv, kahwi agwaduli’a,” Nan nodded, answering before she realized he’d asked her if she’d like some coffee—in Cherokee. She gave him a puzzled look. Most of John’s generation did not speak the language beyond a few quotidian words—hello, how are you?—so she certainly didn’t expect him to correspond in a full sentence. For his part, John turned and opened a cupboard as if nothing was out of the ordinary. Nan decided to test him.

“Tsalagiha hinohvli? Holigas?” Do you speak Cherokee? she queried. Do you understand?

“Goliga,” he responded as he filled the coffee carafe. “Usti giwoni tsalagi. I’ve been taking language lessons for a while at the college.”

Nan smiled and felt her eyes moisten. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I wanted it to be a surprise. It was tough at first, learning all the tenses and the subtle sounds, but I think I’m coming along alright.” He put his hand on Nan’s arm. “I really miss hearing my mom and grandma speak to each other in Cherokee. I realized that if we, as a tribe, don’t do something to educate our young ones, well…Cherokee will just be a name on a casino and nothing more. Maybe you could tutor me?”

Nan rose from the table and joined John at the sink. Her eyes seemed to sparkle with tears. “Hawa,” she agreed as she patted John’s hand. As she rinsed the plates she thought about her own children. None of her daughters spoke more than a handful of Cherokee words, but her grandchildren were taking lessons in school. There was a disturbing paucity of fluent speakers left alive so there’d been a push in recent years to reclaim some of the culture that had nearly been lost completely. Much had been forsaken by John’s generation, but perhaps there was still hope for the young ones. A better place.

And perhaps there was still hope for Pin Oak’s Beloved Woman, too. Nan scooped some flour into a bowl and began a fresh batch of frybread. As she kneaded the dough, she shared with John what Anna May had whispered to her in the ambulance. Through the window she saw Roundboy coming across the yard.

He looked hungry.

Ω

Jamie Cunningham, a Cherokee tribal member (wolf clan), has published in such literary journals as Confrontation and The Iconoclast. He is also an accomplished musician and artist, and has been featured in Guitar World.

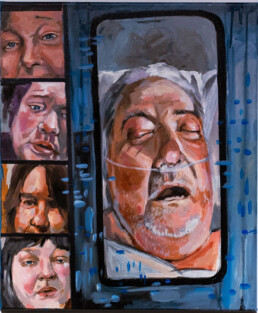

The accompanying image is a painting of Mery McNett’s family on a video call with her father, who was dying in the hospital with COVID. It shows each of them looking at him through a tiny square of video, and his image on the phone, barely conscious. It was the last time McNett spoke to her dad. If you shine a black light on the painting, you will see a hidden message: “I love you, I love you, I love you. Whenever I look in the mirror, I will always see you.” These were the last words she ever said to him. The painting is part of a larger multimedia series, titled “Grief and the Full Cup of Joy,” which centers around the death of McNett’s father, and her pet dog, Gonzo.