Back to the Start

by DINAMARIE ISOLA

My mother and I hurtle down I-95, heading farther away from our old life. I squeeze my eyes shut until moisture pools in the corners and try not to think about how badly I want to poke my index finger into my eye, just to kill what’s building in there. My father, gone; my childhood home, sold. A new life on Long Island awaits me, like clumps of dirt hitting a casket.

The Throgs Neck Bridge looms ahead, a final hurdle for my mother who has never crossed it while in command of the steering wheel. In sparing her this task all these years, my father left her ill-prepared. She exhales, and the vibration travels through me, shaking my insides. I press my eyelids closed with more force and try not to think about the fact that I am in the front passenger seat—the death seat.

She needn’t say a word. I hear it as clearly as if she has called out: Oh Anthony, I need you!

The movement of her hands scrapes against my ear. She grips and releases the steering wheel. She drags her palms, one at a time, down the fronts of her thighs. Her jeans register the movement with a swoosh.

“Jane? You awake?” Her voice is breathy, barely above a whisper, but there is no mistaking her plea. Wake up, please wake up.

Her voice cuts through my conscience. She needs me. I can’t lose myself in selfish, useless dwelling, not now.

“Mmmm,” I groan.

I keep my eyes shut but the sun’s clawing fingers poke at me until my left eye cracks open, and the light hits me like a split to my skull. Why something so beautiful should hurt me so much, I just can’t understand.

She slows as we approach the toll. We have an EZ Pass, but there is nothing easy about being shoved on your way faster than you would like. Coughed up at the mouth of the bridge, we have no choice, no time to second-guess where we are at; the start, again. Face frozen, eyes wide, she seems as terrified about this as I am.

“You’ve got this,” I say. “Keep your eye on the white line.”

She nibbles at her lips and nods. Even though I haven’t scheduled my road test, she listens. It’s something my father would have said, and that familiarity is enough to cause her to relax. He always had a comment, a tip, a direction that could save you some trouble or make life easier.

Stop fixating on the rearview mirror, unless you want to end up in the trunk in front of you.

It’s ironic that now, when we need it most, he isn’t here to direct us. We are kites cut loose in a windstorm. Who knows where we will end up? We still need his guidance.

Sunlight shimmers on the water, coloring it a burnt yellow-orange, like lava. There was a time when I would have snapped a quick picture of it only to revisit it later, with my sketch pad and oil crayons in hand. But since my father’s death, the urge to capture beauty feels like a worthless consolation prize. A million pretty pictures won’t drain the gray sludge that fills me.

We’re midway over the bridge when she calls out, “What lane am I supposed to be in? Jane! Can you read the sign?”

“Right,” I say, squinting into the sun. Being a passenger all these years hasn’t made her an expert in navigation.

“Crap!” She twists her head to view her blind spot, but there is a stream of cars there—people who knew they needed to get right before they even got on the bridge. “I can’t get over!”

The panic in her voice causes my breath to hitch, but then I see it. The sign shows the two far right lanes exit.

“This lane is fine, too.”

“Are you sure?” Her voice pitches higher.

“Stay here.” I raise a shaking finger and point straight ahead.

She blows out a breath and exits along the sharp, dizzying curve which deposits us into a sea of crawling cars and flashing brake lights.

“Hurry up and wait,” she mutters.

We inch along the parkway in the silence, but I know by the rapid pace of her blinks she is trying to find the words to make this impossible situation better.

“I really wanted this year to be special for you.”

Actually, living seems like too much of an effort, but I don’t tell her that; she would only worry. I’m not looking to off myself. It doesn’t matter where I spend my senior year of high school; misery will ride me piggyback wherever I go.

“It’s fine, Mom. I understand.”

I’m not totally lying. She wants to be near her sister, my Aunt Liz; she needs the support. I wonder what it’s like to have a sister who provides comfort. My sister, Jenny, makes my insides coil when she walks in the room. We’re always one second, one snide remark away from igniting. I’m glad she’s at college until Thanksgiving break.

“Brooke is excited that you’re coming. You two get along so nicely.” Even my mother realizes that my cousin is more like a sister to me. “Maybe you can join cheerleading with her.”

“I’ve never been interested in that before. I’m not changing because I’m in a new place, and my cousin is Homecoming Queen.”

She purses her lips and, from the set in her jaw, I know I will never find it in me to ask her to make this drive again. It should make me sad, but I fell away from my friends a long time ago, when my father’s illness consumed everything in its path. It was hard to relate to friends who had stupid worries about clothes, crushes, and grades. I couldn’t relax around them because I felt I should be doing something important, something to change the trajectory. They tried to help me by offering up “fun” activities to distract me, as if my worries could be easily derailed. Couldn’t they see that bowling wasn’t going to fix my world? Every idiotic suggestion reinforced that they could never understand; I was alone.

A familiar, gentle, circular scratching at the top corner of my shoulder causes me to jump. I reach back to grip the hand, expecting my father to be there—but I’m left hanging with nothing but embarrassment. You’re so stupid. He’s gone.

“What’s wrong?” she says.

“Muscle cramp. I’m fine. I just need to get out of this car already.”

“We’re almost there.”

And yet, arriving at my aunt’s house isn’t really where we are ultimately going. Even my stomach understands this; it rolls, drunk on acid as we exit off the parkway and drive through our new town. The flesh-colored water tower greets us like a middle finger.

Living on an island could be my idea of heaven—if it were tiny and deserted. Close to New York City and larger than the state of Rhode Island, Long Island is neither of these things. Lynbrook, with its abundance of cement, strip stores, and supermarkets, has some of the city’s dust on it minus all that “excitement.” The houses are packed together on the street, competing for attention and air. There’s nothing about it that feels like an island. A murky duck pond is the only body of water I’ve seen in this town.

Brooke sits rocking on the porch swing, like a kid waiting for Christmas morning. When she sees us pull up, she squeals and leaps off.

“They’re here!” she calls through the screen door, before bounding down the steps like a pup.

My mother kills the engine before seeking out my hand and squeezing it. It makes me think of a scene from an old movie I watched with my dad. In order to save their lives, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid link up and jump off a cliff. The drop doesn’t kill them.

Brooke throws open my door and yanks me out like I’m a rag doll. “You’re here! You’re here!” she chants.

Somehow everything turns into a cheer with her, but it’s not put on—that’s just how she is. I’m tempted to remind her that this isn’t a slumber party. After a few days of me, she might dial back on her excitement, especially when she realizes that her enthusiasm is no match for my colorless, flavorless world.

Her amber eyes shine at me, a little wetter than usual, and I blink to clear any tears from forming.

Aunt Liz walks down the steps; her smile turns down at the corners. A visit under other circumstances would be so much better than this. The last time we were here, my father was in remission. A fresh start would be ours, or so we thought. I shake my head to rid myself of the sting of my memory.

As Aunt Liz passes me, she brushes her hand against my cheek and kisses the top of my head before heading over to my mother. When they connect, it is a slow embrace that fascinates and perplexes me; I cannot imagine sharing an intimacy like that with Jenny.

Brooke doesn’t unhand me. She clamps on like jumper cables, hoping her energy can infuse me. She shakes my shoulders, as if that will suddenly change the picture and I’ll become my old self; smiling and easy to be around. Unfortunately for her, I’m not an Etch A Sketch.

“C’mon! You gotta see this!” Brooke releases my shoulders, but grabs on to my hand and pulls me up the steps, into her house, and drags me to her room.

“Ta-da!!!” She throws open her bedroom door to reveal her newly renovated space, to accommodate me.

Above one bed is a lofted one that allows me to enter her space without leaving a footprint. Matching pink, floral comforters and pillows, a mountain of pillows, are what catch my eye first. In the corner of the room are beanbag chairs, a TV, and a long desk with enough room for two chairs. It looks like a bedroom from a television sitcom. Everything is perfectly coordinated and cheerful—so freaking cheerful. But life won’t return to normal in thirty minutes, like it does on TV.

“Don’t you love it?”

“It’s really something,” I say. Everything comes out of me in a flat way, like I’m medicated.

“My dad thought to loft my bed above yours.” As soon as she says dad, her eyes start to dart about, and her hand flies up to her mouth.

“That was a great idea.” I force a smile and grab her hand and squeeze it. She looks like she needs the comforting more than I do. I don’t begrudge her having her father.

It doesn’t take long to get settled in her room because most of our things are in storage, for when we find our own place. Brooke smiles as we put the last of my clothes into her closet.

“So, later…” She rubs her hands together. “We’re going to a party!”

“Brooke…” I shake my head.

“Every year there’s this huge party to kick off the end of summer. Plus you’ll get to meet people before school starts.”

Her dark hair shines; her eyes glisten; her excitement crackles, filling the room. She is one of those rare creatures who is mesmerizingly beautiful with a pure heart.

I want to resist her, but one look at her face—all glowing and hopeful—and I figure one of us should get to experience that exhilaration. I’m beaten down, too exhausted to fight.

“Pretty please?” Her palms touch flat against one another like she’s praying.

“Okay,” I say. “But I don’t want you making a big deal; no parading me around.”

She lets out a victory squeal. “Let me braid your hair; turn around,” she commands. “You can take it out if you don’t like it.”

And for a sweet girl, she sure knows how to be pushy. The braid is just the start. Off my teary protests, she rips out my eyebrow hair, telling me I have to suffer to be beautiful. I almost tell her that emotional suffering must not count; otherwise, I’d look like her.

Next comes makeup and, of course, she doesn’t stop there. She pulls clothes out of her closet and settles on a baby-doll dress for me with cork wedge sandals. By the time she finishes, I look like an entirely different person—not bad, just not me.

If only I could become this girl who is looking back at me in the mirror, maybe I could get through this year. But the truth is I am an impostor. With or without this makeover, this isn’t me. I don’t even know who I am anymore. This chapter of “life after” seems to have wiped out all record of who I was before, and I can’t piece myself back together.

I want to tell Brooke this as she rushes off to shower.

I want to wash the makeup off my face. I want her to understand why I can’t go to the party. But everything is happening to someone else—to this girl in the mirror without any troubles.

I lay back on my bed, and that’s when I notice the collage Brooke attached to the underside of her bed. As I look at the pictures of our families together—summer barbeques, Thanksgiving feasts, vacations in New England—my eyes fill; three words come to mind. In happier times.

I spot a picture I never saw before—my father caught in mid-laugh, his eyebrows tilting toward one another. It’s been so long since I’ve seen him as I want to remember him, vibrant and strong before disease ravaged him. I take out my phone and snap a picture of it, but it’s a grainy copy of a copy.

I force down my shoulders that suddenly have risen up to my ears, but it does no good. The steely hand of grief presses on me, like an anchor. If I move, can I shake off this weight that bears down on me? Nothing is the same. Nothing will be the same, and looking back at it will always be a painful reminder of happier times.

I imagine my father, telling me about the dangers of fixating on the rearview mirror. I don’t want to end up in a trunk, but maybe I’m there anyway. Maybe there’s not much more to fear?

How many nights have I awoken in a sweat, desperate to save his life before reality punched me? He’s gone. It’s over. And through my tears of anguish, there is one truth. I have no choice. There is nothing I can do to change the outcome. Accept it and move on. But there’s relief too. He’s not suffering.

Brooke comes back from her shower, wrapped up in a towel. She stands still when she notices that I’m looking at her work.

“Thanks,” I say, pointing to the collage. “It’s beautiful.”

Her eyes well up. “Want to blow off this party?”

I nod. “You go.”

She shakes her head. “It’s okay.”

I don’t need her to sit with me, but she does. She even goes off and gets me paper and a pencil. And as I work to capture the picture of my father laughing, I make sure to add the details only I can—the faint shadow of his dimple and the gleam in his eye.

Brooke rests one hand on mine, the other against her chest. Then she pulls the pencil from between my fingers and draws a faint circle on his left cheekbone, his chicken pox scar.

“We’ll get through this.” There’s no “rah-rah sis-boom-bah” in her voice, just a crack of pain that vibrates in me. But as I allow her ache to settle into mine, there’s a strange comfort that washes over me. He may not have been her father, but she’s lost him too.

We sit, passing the pencil back and forth, taking turns embellishing his features. We capture all that has been taken from us; the life he brought into a room with his smile, his laughter. When we finish, there he remains with his essence intact. And for the first time in months, I feel my lungs expand like I’ve only just learned how to breathe. Even though I know grief will be mine, this loss will never leave me, Brooke’s eyes glisten with a promise. I won’t be on my own.

Ω

Dinamarie Isola uses poetry and prose to explore the isolation that comes from silently bearing internal struggles. She received her BA in English/Writing and Communications from Fairfield University. In addition to working as an investment advisor, Dinamarie writes a plain-English personal finance blog, “RealSmartica.” She is a member of the Women’s Fiction Writers Association. Her work has been published in A Thin Slice of Anxiety, Apricity Magazine, Avalon Literary Review, borrowed solace, Courtship of Winds, Evening Street Review, Five on the Fifth, Penumbra Literary and Art Journal, Potato Soup Journal, Nixes Mate Review, and No Distance Between Us.

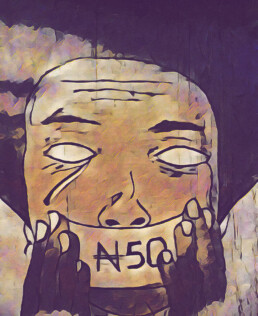

Moses Ojo is a young Nigerian artist who uses his mind as a vista for making captivating art. His brushes and watercolors thereby speak reality to viewers of his arts and crafts.