Kung fu

by KATE NOVAK

“Asia! Asia! Hey, Asia!”

The window is open, and Korek’s voice calling my name seems to be pulling at the curtain, which is moving with the dry wind. It’s one of the first hot days of June; soon summer will be here. I just have to pass the last exams at school and the long, warm days will stretch before me like a roll of silk. Even in an eastern European town, on the flat, uninspiring plain, summer still manages to pull off its trick: the beginning of the season is as full of promise here as elsewhere.

“Asia!”

I lean out of the window.

“I’m studying.” There are three of them there. I didn’t expect to see them, especially not Weder. In the sun, his dark hair looks navy-blue. He’s looking at something in the dirt.

“What are you studying for?” Korek asks.

“I’ve a history test tomorrow.”

“You study and study.”

“Not true. I hung out with you guys yesterday.” I rub a tiny wine stain on my t-shirt. I haven’t changed it from last night because it’s my lucky Bruce Lee t-shirt. It helps with studying.

“Yeah, but that was last night. Come out, take a break. We’ll go for a ride.”

“A ride?”

“Garstek has a car.”

Now that’s unheard of. I close my books and I put on my new necklace, the one I made to wear to the party and then forgot to put on. It’ll cover the small red stain. I’m not used to this sweet wine. It made my head swirl. I hadn’t expected it to be pleasant. I go downstairs.

“Where did you get the car?” I ask.

“A friend lent it to me for the afternoon.” Garstek has curly blond hair, the dusty golden shade, and fat lips that always look a bit wet. He blinks his myopic eyes nervously, unsmiling, even when he laughs his forced laugh. Maybe it’s because he’s so ugly that he thinks he’s smarter than everyone else; maybe he really is smart – I haven’t decided yet.

Garstek opens the door of an orange Fiat.

The small Fiat, a.k.a. “maluch,” was the Volkswagen Beetle’s uncool, crude, and poor second cousin, twice removed. But it was still a car: an imagined status symbol and a real object of desire. Maluch was the most common car in an era when cars signaled luxury and wealth; second-world style. Under communism everyone was supposed to be equal, but humans seem to dislike equality instinctively, seeking, yanking out, and obsessing over the tiniest difference to valorize and parade as a sign of superiority. To the untrained eye, those differences were negligible, but communism trained our eyes well. If you had a car – even a maluch, the three-door tin with plastic seats and an engine comparable to that of a coffee grinder – you were a whole class above the rest of us, who walked the earth instead of driving.

“Get to the back seat,” Korek tells me.

“She’s riding in the front. You go to the back,” Garstek says, and Korek obeys, saying nothing. If Garstek is ugly but maybe smart, Korek is neither. His face resembles a potato both in texture and color, and, come to think of it, his head is shaped like a potato as well. If I touched it, I’d expect to find small sprout knobs; but I’d never touch it.

“Move over,” Korek says to Weder, who responds with a distracted, “Hmm?” Garstek pulls down the front seat for me, closes the door behind me, and then gets in.

If I lean over closer to the door, I can see Weder in the side mirror. He’s not looking at anything in particular, and definitely not at me.

“Do I have to wear a seat belt?” I ask.

“You don’t have to,” Garstek says, “but it’s for your own safety.”

“As a matter of fact, more people die in accidents and become crippled for life because of seat belts, but nobody will tell you that,” Korek says.

“Nobody will tell you that, because it’s not true.”

“It is! It’s statistically and scientifically proven.”

“Korek, you’re statistically and scientifically an idiot.”

“Weder, tell him.” In the constant quibbles between Garstek and Korek, Weder is the arbiter, but he responds with his usual, “Hmmm?”

“And where did you hear that, anyway? Like, there was some kind of a study to see if seat belts cause accidents? Like, they thought, oh, we’ve been putting seat belts in cars, but what if they cause more harm, is that it? Did they call you as an expert on this, or did it all happen in this big head of yours?” Garstek knocks on his own head with his fist, which is surprisingly small.

“Watch the road,” Korek says, sulking.

“And what do you think, miss Asia? Do seat belts cause accidents? Do they maul people?”

“Like she would know,” Korek cuts me off. “Besides, I never said they cause accidents. I just said that in accidents they are proven…”

“You are proven to know absolutely nothing of what you’re talking about,” Garstek laughs, and his thick lips glisten with saliva.

If I lean my head against the door, I can pretend to watch the street. Weder is wearing a black t-shirt, maybe the same one he was wearing last night. His black eyebrows are pulled together in concentration as he’s tracing something distractedly on the glass with his finger. His thick black hair is pulled into a ponytail at the nape of his neck. And then he looks in the mirror and smiles at me. He knew I was watching him all along. Korek looks first at him, and then at me. I twist my necklace around my finger: one loop, two loops. I made it out of dry pasta and painted it red and yellow and green. Summer colors, bright and cheerful.

“They are a safety device,” I say.

“Exactly!” Garstek exclaims. “They are there for your safety,” he says it slowly, turning to Korek, stressing each word, like he was talking to an idiot.

“Oh yeah? Did you use a safety device last night?” Korek asks me.

“Don’t be mean,” Garstek says.

“Weder, did she use a safety device?”

“Shut up,” Weder says.

I inch away from the door to avoid meeting his eyes.

“Did you?”

“Change the goddamned subject, Korek.”

We ride along the dusty streets. Soon, the apathetic greenery of the squares will be trampled by the kids, once school finishes. There isn’t anything to comment on. Same streets we’ve known all our lives, same grey dust, same miserable patches of grass.

“What’s Monika up to? Why hasn’t she come with us?” Korek asks. Monika is Weder’s girlfriend. I don’t know the answer, but they surely do. Nobody says anything. I pull at my necklace. One loop around my finger, two loops, three.

“Asia, if Weder proposed to you, would you want to be his wife?”

“Korek, next year she’s finishing high school,” Garstek says. Garstek, Korek and Weder are two years older than me. Garstek is my cousin, and Korek and Weder are his best friends. They all went to primary school together. Up till last year, they ignored me completely, as a child. Whenever Garstek’s back – once every six months or so – we hang out. Garstek studies at a university (maybe he is smart, after all?) in Warsaw, which seems a whole universe away from here, a small town in the south of the country. I’m curious about his life out there, but it seems so strange that I don’t even know what questions to ask. If I get into the university next year, I’ll learn all about it my own way.

“That doesn’t answer my question. If he wanted you to be his wife, would you?”

I turn to look at him reproachfully. My necklace catches on the seatbelt and the thread breaks. Pasta beads spill on my lap and on the floor.

“Oh my god, you would! Did you see that?” He turns to Garstek. “She totally would! Would you like to have his babies?”

“Korek, goddammit…” Garstek says impatiently.

“No, no, let me, because I’m sure that’s something they didn’t discuss in the heat of the moment, did you, Asia? You never told him that you’d like to be his wife, did you? So poor Weder is thinking that he’s just lucky to get laid at a party when Monika is away, while in fact he’s being manipulated into something much, much bigger!”

I don’t know what to do with the colored pasta; it’s staining my hands. They must be getting sweaty. I notice marks of paint on my t-shirt as well. I was planning to wear it tomorrow to school. And now it’s ruined. I roll down the window and chuck out the pasta beads.

“You’re such an idiot,” Garstek says to Korek.

“I think I want to go back.” I turn to Garstek.

“But we haven’t even left the hood,” Korek says.

“Shut up,” Garstek says. He’s not looking at me. He’s watching the road. Suddenly he turns the wheel to take a U-turn. I am pushed against the door, and I see Weder briefly. As the car’s turning, the door flies open. I catch it in a wide, Kung fu-like gesture, and pull it shut. There is silence, and then Garstek bursts out laughing. He laughs and laughs, and then Korek joins him, and then, hesitantly, Weder. They are all laughing till they’re out of breath.

“She could’ve ended up on the street. Imagine if she wasn’t wearing a seat belt,” Korek says.

They drop me off by the entrance to my building. I go upstairs to our flat. I wash my hands in the bathroom, put my t-shirt in the washing hamper. Even if I wash it now, it won’t be dry by tomorrow morning. I go to my room, and I try a karate-chop in front of the mirror. My history textbook lies open beside me, but I don’t feel like reading it. I lie down on my bed.

“Dinner’s ready,” my sister comes to tell me.

“I’m not hungry.”

“Why are you lying here like that?”

“Like what?”

“With just a bra on? Where’s your t-shirt?”

“It got soiled.”

“Soiled?”

“Stained.”

“I told you the pasta necklace was a stupid idea.”

I say nothing.

“Well, if you want to join us, dinner’s ready.”

“You already told me.”

“Whatever.”

She goes out of our room back to the kitchen. The wind is pulling at the curtain. There are distant voices of children, playing with a ball. The evenings are getting longer and warmer. The blue light fills the room slowly, first erasing the sharp edges, then obliterating all. I watch the light square of the window get darker and darker. I try one more pose in front of the mirror, legs wide and bent, one arm behind me, another in front, with fingers outstretched, welcoming whatever comes. I make a Bruce Lee noise, half-squeak, half-scream. Maybe if I use a hairdryer I can wear my lucky t-shirt tomorrow, I’m thinking. I’ve been studying, I know I can probably get an A without it. But I’m going to need a lot of luck later.

Ω

Kate Novak is a feminist, immigrant, vegan cat lady. She writes about what she considers important: being an outsider, speaking from the margins, and representing a minority perspective. She teaches American literature and writing. She is passionately anti-anthropocentric. Kate has published several short stories in online and print magazines, including Fairlight Books, Eunoia, The Bookends Review, Literary Yard, and Literature Today, volume 7. She also writes academic books and papers about literature, culture and translation. She has two novels in preparation, which she hopes to publish one beautiful day.

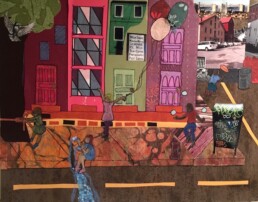

Ann Calandro is a writer, artist, and classical piano student. Her short stories have been accepted by The Vincent Brothers Review, Gargoyle, Lit Camp, The Fabulist, and The Plentitudes, and other literary journals. Duck Lake Books published her poetry chapbook in 2020. Calandro’s artwork appeared in juried exhibits and in Mayday, Nunum, Bracken, Zoetic Press, Mud Season Review, Stoneboat, and other journals. Shanti Arts published three children’s books that she wrote and illustrated. See more of her work at anncalandro.webs.com.