Racecar is a Palindrome

by ROBERT REEDY | 3rd Place, student prose contest

The splendor of the world has been enriched by a new form of beauty, the beauty of speed. A racing-car adorned with great pipes like serpents with explosive breath…

—Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944)

Even before I was born, I loved racecars. While pregnant with me, my mother worked on the pit crew for my dad and his co-driver Ernie. They competed in purpose-built cars on actual racetracks. According to Mom, Ernie raced a car that drove me wild. The baritone shout of an un-muffled inline six at full boil, rising amid the roars, pops, and yowls of the other cars always got me going. It wasn’t the volume. I didn’t react at all when other loud cars drove by. But every time Ernie opened the throttle down the front straight, I kicked furiously. I guess I could have hated it. I don’t remember it at all, as my mother hadn’t given birth to me yet. My personal memories of cars start when my brother was about to be born.

The moment has crystalized in my mind.

I was almost five at the time. We lived in a California apartment complex with a covered parking lot. Each space had a little curb at the top, so cars didn’t roll into each other. My mother was going into labor. Dad sprinted to the Jeep while Mom and I toddled over to wait until he brought the car over.

I watched as Dad threw the Jeep into gear, his mustache bristling, gaze intense. He floored the accelerator, and the Jeep lunged straight forward, over four rows of parking curbs, bouncing crazily, directly toward us. I remember it flying, hopping like a frisky billy-goat. It looked as if it was excited to meet the newest member of the family! I thought it was awesome. My mother thought we were going to die; she inched around a steel support beam, in the midst of a contraction.

Luckily, nobody died. Indeed, two things came to life that day: one was my brother, and the other was my belief that cars were alive. That wasn’t a big logical jump for the mind of a child. There are so many complex moving parts in automobiles that many adults are clueless as to how they work. They might as well be alive, or magic, or both. To a small child, cars absolutely qualified as both.

A year later we moved from California to Oklahoma. At that point, the trip was more miles than I had traveled in my entire life. The mover’s truck we used was a totally new experience for me, exotic and special in its novelty. Its sides were billboard signs! Its bulldog nose snorted away loudly under a heap of billboards on its forehead, huge and grumbly, even while parked. The seats were so high, and I could see so far! Its cavernous body concealed our entire life and effortlessly carried it an impossible distance away. Is this alive too?

On that multi-day road trip, we drove down endless arrow-straight sections of desert highway. Riding in the truck with my mother, I asked silly questions, as young children are wont to do. One such question was as old as motor vehicles themselves, perhaps even carriages and wagons, “Mom, can I drive?”

I’d asked the question before and was always met with a smile and a firm, “No.”

That time, I only got the smile.

I stared in growing wonder as my mother’s eyes flicked from the empty stretch of highway ahead to the door mirror and the uninhabited road behind us. To my infinite amazement, she scooted back in the bench seat of the large, fully loaded, diesel-powered moving truck and patted her lap.

“You can sit on my lap and steer. Just keep it going straight between the lines. Hurry up, before I change my mind.”

I was awestruck and overwhelmed. I found my butt on my mom’s lap, staring forward intently, with my hands locked on the steering wheel so that it couldn’t move an inch. I was driving! The truck lazily drifted to the edge of the lane and onto the shoulder.

No truck, I said. Go that way! I’m not moving the wheel!

“Whoa there, keep it straight.” My mother’s hands covered mine as she calmly and gently corrected us back to the center of the lane. This happened twice more, then I found myself back in the passenger seat. Mom explained while she drove. Turns out you can’t just hold the wheel straight; you must wiggle it around to keep the truck between the lines. You had to keep reminding it which way it was supposed to go. The truck moved on its own as if it was a horse. As if it were alive. Incidentally, that very same truck spat its driveshaft—the part that lets the engine move the wheels, more or less—out from under it a few days later, just miles short of our destination. The beast was displeased! In my eyes, cars became wonderful, inscrutable, temperamental creatures, easily angered.

My father stopped professionally road racing when we moved to Oklahoma. He never sold his racecar though. It traveled inside the moving truck with all of our other things. It was a fixture of my early suburban childhood. A pale, oxidized-blue, two-door Fiat gutted and roll-caged, driver net hanging in the window. I never gathered what year or model it was. It was timeless. Its name was Runt. The rare glimpse under Runt’s hood revealed dust and a surprise, four little trumpets pointed at the clouds. A four-cylinder?

“Son, more isn’t always better,” my father informed me when I asked.

Runt was parked behind the garage. That was his home. Runt was always a male in my imagination. Year after year, wasps built nests in him, rain pounded him, snow and leaves hid him from view. He was always there, sleeping behind the garage. Runt was a testament to days long past, and food for my wild imagination. Every time I visited the garage I saw it as his closet, which always held extra tires on extra wheels, hanging on bars from the ceiling, dark and forgotten. Dust powdered the sticky rubber. A forgotten shrine to a slumbering god.

When I was about ten, my father decided it was silly to keep a racecar and never run the engine. If it never ran, it would eventually freeze up. Then it would be completely useless, not compelling enough to justify its own existence anymore. The dreams of one day racing again would be as dead as the car. My mother push-started Runt using the same billy-goat Jeep from the parking lot, and that slumbering god woke once more, tearing its way into the world of the living.

The noise was incredible, cacophonous, and even ugly. If there was a chainsaw the size of a car, I imagine it would sound like Runt. Commuter car engines redline at around six-thousand rpm, Runt’s was something like twelve thousand. And his sound wasn’t the well-organized song of a fast motorcycle. It was a large caliber pistol firing two hundred rounds a second. The sound of tearing paper broadcast on a thousand megaphones. It was the loudest sound I had ever heard, and it was magnificent.

My whole life, Runt had been silent. A sleeping presence in the backyard. Now, his enforced silence had been broken.

Dad didn’t keep him out for long.

“Just enough to stretch his legs,” he later said.

I barely remember seeing him take off, but I will always remember the noise. Runt shouted down to the corner and turned into the neighborhood behind our house. Then there was an unholy roar. I could hear Runt tear down the street, unable to see him, but tracking his progress easily. Another corner, another bold roar. The final stretch seemed to go on longer than the others, as if Dad kept the throttle open just a little longer, unwilling to end the moment. I remember the gravel popping beneath weather rotted tires as Runt rolled into the yard, still chattering away at four-thousand rpm even while idling. Then it was over, and the only sound left was the ringing in my ears. Runt’s silence echoed once again.

We moved again to another city in Oklahoma, and my dad’s attention shifted to dirt-track racing—which was much cheaper than road racing. Runt lived behind the garage at our new house too and would be largely forgotten for years, waiting for someone to wake him again. My imagination also moved on to other things, like the alcohol dragster down the street.

Incidentally, there was another racecar and driver in our new neighborhood. Our family called him ‘Racecar Ralph’, though in my imagination, his name will always be Alcohol Dragster Guy. As the names imply, he had an NHRA racing license and a long-body alcohol-fueled dragster like the ones on TV. That exotic beast lived behind a wrought iron fence, like a dangerous predator at the zoo. I never saw the dragster in a race, or even move on its own. It was only practicing, like a lion cub who just can’t wait to be king. When you race a car regularly, you must work on and test the engine. Dragster exhaust pipes are just little tubes to get the flames away from the motor, they have no muffler. So, whenever Ralph tested the motor, the whole neighborhood knew, and I came running. Racecar Ralph was friendly and patient with excitable children asking endless questions.

It amuses me to think that the dragster might have intimidated poor Runt. The noise it made was glorious, truly the sound of an angry god. Much, much louder than anything else I had heard in my life. It put Runt’s buzzing to shame! It was like constant thunder, a lightning storm overhead despite clear skies. Even with my hands covering my ears, it was impossibly loud. I felt it. My whole body, my vision itself—my eyeballs—shook! Every time I watched or listened to that car I was awestruck. That car didn’t live in my backyard though; it wasn’t my car. That car wasn’t Runt.

Around that same time, my father teamed up with a coworker to race on dirt tracks for some years. It was real racing, but much more affordable than road racing for a father of two. Many types of cars, all racing in different classes with other, similar cars. They tore around a clay oval, like tiny, muddy NASCARs.

I learned that welding is like car surgery. I saw a car go from salvage to race-ready in a few months. Then we got to spend time at the dirt track! Racecars in various states of assembly were everywhere, wrenches turning to the constant backdrop of announcer chatter and engines. Trucks, trailers, pit bikes, ATVs—the racetrack had everything a growing boy could ever want. There was racing too. I mostly ignored that. I learned to appreciate circle racing much later in life, but at the time it held little interest for me. I wanted to explore the pits constantly! It was absolute heaven for a nerdy, ADHD preteen. Secretly, I was searching for another Runt. Did any of these people have pet racecars? I honestly don’t remember if dad or his partner ever won a race on dirt.

The last time I saw a racecar in person, I was a young teenager. Dad had waited years, but finally, it was time to justify Runt’s existence again. Billy-goat Jeep was long gone by this point, so a neighbor attached a tow strap from Runt’s front tow hook—an especially useful feature all racecars have—to his truck’s trailer hitch. I watched from the curb as the tow strap tightened and the cars rolled forward. Dad eyed the speedometer and threw the car into gear at the proper speed. The rear wheels chirped as the engine coughed, sputtered, and roared. Runt wasn’t as loud as I remembered, but it was still an unholy noise. They shook the tow strap loose, and dad raced to the end of the street. Then he stalled the engine, and Runt sputtered out again.

They reset their positions; the tow strap tightened. Just once around the block to make sure it’s still working! There was one fateful cough from the exhaust, then the mournful shriek of protesting rubber as Runt’s little engine seized completely. The truck was still pulling at fifteen or twenty miles per hour when it happened. The inertia, the mass, the sheer force involved, still tried to turn the rear wheels, but the engine itself had frozen entirely. Something had fused together or broken to lock it in place. The engine could not turn, and that force had to go somewhere. In a desperate last stand, Runt lifted on his hind wheels in a mockery of a wheelie, his body twisting somehow, even though he had a roll cage. I distinctly remember the tow strap creaking with tension, like a tree mid-fall, stretching perilously close to snapping. I ran towards the back of the truck, in a misguided attempt to pop the tow strap loose. All I could think at the time was that Dad was in trouble.

That moment was the first time I ever saw my dad genuinely panic. He raised his hands from the steering wheel, hanging from his racing harness and seat, and gestured at me wildly. His eyes were white all the way around, and he shouted so forcefully that spit sprayed from his mouth, “Get away! Get back! BACK!” I ran back to the lawn, shocked and overwhelmed.

They quickly sorted out the situation. The truck backed slowly to lower the car to the ground, then retrieved a trailer to move Runt out of the road. That day I learned that straps under tension could snap violently, and even kill. I learned something else too. I knew years before that day that cars weren’t alive, just incredibly complex machines. However, that day some of their magic died. They were no longer mythological creatures, temperamental and tempestuous. I learned that cars could die.

Years passed by. I grew up, spent time in prison, and then moved away. I didn’t buy my first car until I was in my early twenties. A 90s hatchback. Her name was Reba because I could never properly remove the Reba McIntire bumper stickers that had baked onto the poor car over fifteen years of sun. Her red paint was even more oxidized than Runt’s paint from my childhood memories. I bought Reba from her previous owner for the princely sum of one hundred dollars, which my boss loaned me. Very early on in car ownership, a combination of the flu and sleep deprivation led me to have an accident. Reba got thrashed but was still drivable. The passenger side doors didn’t open anymore. I stopped babying my car after that. Reba and I explored the mechanics of car control and the limits of performance by driving incredibly irresponsibly on the dirt and gravel county roads around my town.

Though it had been years, I began to feel the magic again! Slowly, as we played and explored, Reba and I found the secret of racing. We found the reason it exists. It is the sheer visceral sensation of driver and machine working as one. The feeling of your insides moving and shifting in response to the car. The ‘seat feel’ that drivers talk about. When driver and car become as one, they are far more than the sum of their parts. They become a new animal, a racecar.

The spell broken in my childhood sparked into life once again. The embers of memory flared into the fires of passion. Like the Olympic flame, the dream was passed on to another. From then on, whenever I was driving, in my heart, I was part of a larger whole. A racecar. Runt would be proud.

Ω

Robert Reedy is currently pursuing his second Associate’s Degree at TCC. He is 35, married, and incarcerated at Dick Conner Correctional Center. He hopes to write professionally in some capacity.

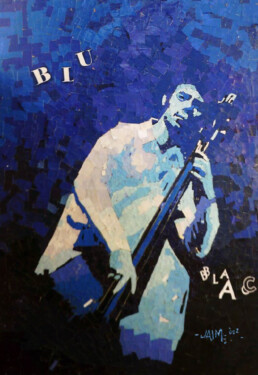

Jamie Cunningham, a Cherokee tribal member (wolf clan), has published in such literary journals as Confrontation and The Iconoclast. He is also an accomplished musician and artist, and has been featured in Guitar World.