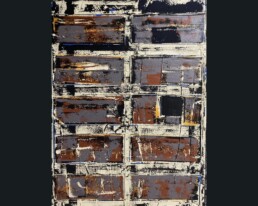

Boxes

by SAMUEL LEE REGAN | 3rd Place, student poetry contest

I am stacking memories,

Cramming my house from floor to ceiling.

Accumulating dazzling treasures,

Just because I can.

I am like a beaver.

Building a dam—to hold in my grief.

I am like an Egyptian Pharaoh.

Collecting things for entertainment in the next life.

I am happiest this way,

In my quiet maze,

Surrounded by my abundant wealth.

Ω

Sam Lee Regan is a Cherokee Nation citizen, visual artist, and writer. As an Indigenous artist, much of Sam's artistic practice is based on the importance of reclamation, rematriation, and personal/communal understanding. They are interested in better understanding the connections we have as humans with the land, animals, our ancestors, our minds, and our bodies. As a multi-disciplinary artist, much of their work is interconnected. Their inspiration comes from interpreting life through the lens of an intellectually hungry and curious being. They have an insatiable thirst that can only be quenched through the drinking of life, its beauty, and sorrow.

Mark Rosalbo was raised in Leeds, Maine. He spent much of his early childhood exploring the banks of the Androscoggin and Dead Rivers, the latter one of only a handful of rivers in the world that can flow in either direction. Early socio-economic hardships shaped much of Mark's artistic choices as a composer, actor, and painter. Many in his circle, including his brother, succumbed to various cancers like Leukemia as a result of living along Maine’s rivers once polluted by paper mills. After graduating high school, Mark moved to Los Angeles to study at The American Academy of Dramatic Arts. After graduating from AADA, he moved to NYC and remained in the city until shortly after 9/11, when he moved his family to Vermont to enjoy the banks of (this time much cleaner) rivers. More of Mark's work can be viewed at solo.to/markrosalbo.

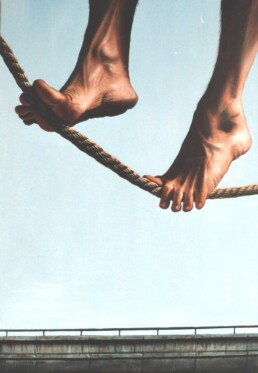

Self-Medicating in the Apocalypse

by SIMON KERR

The empty world funnels into an empty parking lot, funnels into an empty Walmart, funnels into an empty Walmart Pharmacy, funnels into an empty staff bathroom, funnels into an empty syringe.

I can fucking do this.

I searched nine pharmacies before I found a vial. Liquid gold, little lad juice, the Hormonal Grail. Testosterone, baby.

There’s no internet now, but the night Before, my repressed ass skidded right down a YouTube spiral of vloggers cataloguing their transitions. I avoid looking in the unpolished mirror, in front of a sink not conducive to medical procedures.

“This is my voice one day on T,” I say, going low like I’m trying to sing Hozier. Then I go up for Bowie, “This is my voice four weeks post-apocalypse!”

I feel like I can’t complain. Being still alive and all. All told, it was a pretty fortunate apocalypse. I’d have preferred if pop culture was wrong about the undead altogether, but at least it was wrong about the never-ending hoard aspect. They starved pretty quickly, after decimating their own food source. No mind for sustainability.

So, the dead are dead, and the undead are also dead. Everyone’s dead. But me. Maybe. And I’m headed… I don’t know. I was focused on pharmacies. From the deep south to the less deep south, for starters. Maybe the east coast, maybe the west.

If I’m honest, do I really miss society that much? It was mid.

“Yeah, quit stalling, man,” I mutter.

With no doctor to consult, I’m picking .30 milliliters. I uncap the needle on the syringe, and I feel the can of peaches I savaged my way into reintroduce itself to my esophagus.

It’s fine. I can fucking do this.

I impale the gray membrane on top of the vial and realize I forgot to warm it up in my hands, then decide that’s probably not that important.

I tip the vial upside-down to draw and—wow, it’s a lot more stubborn than I thought. I tug at the plunger, and it doesn’t want to be tugged. But there’s some yellowy bubbles, which form some yellowy liquid. There’s .05 milliliters. Ish.

It takes a few minutes. I hope I get better at this, in case I have to run from a bear at some point.

Oh shit, are animals gone too? I haven’t been paying attention.

“Quit. Stalling.” I take a deep breath and make eye contact with this stubby little needle.

It makes eye contact back. We don’t like each other.

Doesn’t matter. I can fucking do this. This thing is going in my ass. I’ve seen it on YouTube.

I shuffle down my undies. Boxers. I roll out my shoulders so I can reach back, squeeze a bit of fat to puncture, aim the syringe like a dart, and—

Holy, holy fuck; I can’t fucking do this. What was I thinking? I can’t stab myself, in my ass or elsewhere. Society has ended! This doesn’t even matter!

I exhale like an indignant horse and put the needle down. Shake out my hands.

I spend a minute breathing. Two. I don’t look at my reflection. I haven’t, not directly, in months.

It matters.

Clenching my teeth squares my jaw. I pick up the needle again.

I can fucking do this. No: just fucking do this.

To distract myself, I start humming, bobbing my head, missing Spotify. “Don’t make it bad.” Inhale, exhale. Turn, squeeze. “Take a sad song—and make it better.”

“Rememb— AH.” I yell at myself when the needle prods me but doesn’t go in. “Remember! To stab yourself in the ass!”

Needle, positioned. Pressure. Pressure… Why is it taking this much pressure…

It slips in, and I lurch.

“Ow. Okay. Then you’ll begin…” It’s hard to depress the plunger at this angle, and my micro-wiggling is not helping the ouch. “…to make it better.”

Suddenly, the plunger won’t go any further. I bend to look. It’s down. It’s in. I’m officially one minute on T.

I laugh. A little manically. I look upward to thwart the tears. I fucking did it.

I meet my eye in my reflection.

“Hey, Jude.”

Ω

Simon Kerr (he/they) is a speculative fiction writer in Colorado. His interests include tea, feline antics, and that one book you just can't describe but you want everyone to read.

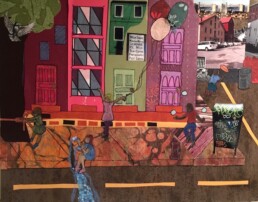

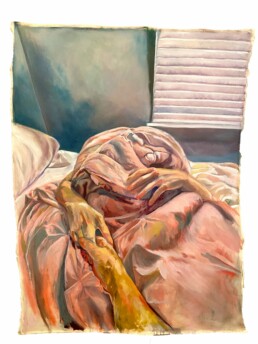

Sean Tyler is a muralist and fiber and mixed-media artist from Tulsa, Oklahoma. Tyler earned her BFA in studio art from Rogers State University in 2019, her MA in painting at the University of Iowa in 2022, and is currently completing an MFA at the University of Iowa. She has shown work across the United States and has murals installed in Iowa and Oklahoma.

Deaf Wannabe

by PAUL HOSTOVSKY

We were sitting right here in this living room, talking about Deaf things. Michelle said the new superintendent at the school for the Deaf is hearing, but he signs like he’s Deaf. And the chief executive officer, she said, is Deaf, but she signs like she’s hearing. RIGHT-RIGHT, said Marlene with a disapproving scowl, a sign that means “how typical and how wrong.” Then Janice signed some untranslatable pun which really tickled our philtrums and we burst out laughing, shaking our heads at the truth of it. And then, as it has a way of doing, the conversation turned to cochlear implants.

Janice said the CEO has a cochlear implant, and Marlene said it’s rampant discrimination, that’s what it is, the way ASL Deaf are consistently brushed aside and passed over in favor of oral Deaf. TALK-CAN JOB OFFER-YOU, she said. And Michelle said that Stan, the hiring manager at the Commission for the Deaf, had asked her at the beginning of her job interview if she preferred to talk or to sign. The question was offensive and discriminatory, she said. ME DEAF SIGN-ASL, she replied to Stan. She didn’t get the job. And Janice said that Stan has a cochlear implant. And Marlene said she wouldn’t be surprised if one day one of the 90+ percent of Deaf kids getting implanted as young children goes postal as an adult and shoots up an entire audiology department. And we nodded in agreement, then shook our heads at the truth of it.

And then Marlene said something that threw me. She said if there were a way for her to be hearing, if the cochlear implants really did make you hearing–which they don’t, they definitely don’t–she would choose being hearing in a heartbeat. And I said W-H-A-T? And she said, DEAF HARD. And I gazed deep into her peerless eyes. And she said YOU NOT-UNDERSTAND YOU HEARING. She went on to say she loved ASL and she loved the Deaf community but bottom line, it’s hard being Deaf. It’s a hell of a lot easier being hearing. And Janice and Michelle both said, NEXT, which basically means “I second that.” Or a more apposite translation might be: “Hear, hear.”

And I was totally thrown because, here I’d been learning ASL and hanging out with Deaf people all these years, and I’d always been taught that Deaf people are a linguistic and cultural minority, that it’s all about Deafhood–not deafness–and that audism (which Merriam-Webster added to the dictionary just a couple of years ago) is the prejudicial belief that it’s fundamentally better and more desirable to be hearing than to be Deaf, a notion that Deaf people have always told me they reject because it’s ethnocentric and false. And here was Marlene telling me she’d rather be hearing than Deaf. And Michelle and Janice were saying “hear, hear.”

And being the sole member of the hearing debate team in the room–in the house, actually, which is a Deaf house–I raised my hand and said, EXCUSE-ME, WHAT ABOUT DEAFHOOD? WHAT ABOUT DEAF-POWER? That’s when they lit into me and said that hearing people who learn how to sign and then go sounding off about the beauty and legitimacy of ASL and Deaf culture, well, it smacks of cultural appropriation. YOU THINK YOU UNDERSTAND DEAF YOU NOT! said Marlene. YOU DEAF NOT! said Michelle. Janice just smiled at me knowingly, and her laughing eyes were saying RIGHT-RIGHT (“how typical, how wrong”). And then they gave me a good talking to. They said I was just an amateur, a visitor, a tourist admiring the trappings of being Deaf, sampling the language, the culture, the humor, the visual vernacular and virtuosity, but at the end of the day I didn’t live it. At the end of the day I went home to being hearing, they said.

But my home is with you, I wanted to say to Marlene, who, I neglected to mention, is my wife.

She and Michelle, her twin sister, are Deaf. And so are their two older sisters, their niece and nephew, and one of their aunts. And so is my brother-in-law Rob and my brother-in-law Phil. There are also a few Deaf exes in the mix. So you see, I have married into a rather large extended Deaf family. And in the Deaf world, Deaf families are a kind of aristocracy. Where Deaf is the currency.

Nevertheless, Marlene’s hearing family members still outnumber the Deaf family members because it’s a large family. But at the family gatherings I always hang out with the Deaf contingent, even though I’m hearing. Because the Deaf family members are funnier, and more fun, and they seem to have more experience with the happy varieties of their subject matter. So I’m kind of an honorary Deaf member because I married in. I’ve been granted a seat at the table. And by now I have a handle on the language. And a small window onto the Deaf experience.

But here was my wife saying to me: YOU THINK YOU UNDERSTAND DEAF YOU NOT! Of course, I would never claim to know what it’s like being Deaf. For example, I don’t know what it’s like for her when I’m not with her–because I’m never with her when she’s alone, obviously–when she’s out in the world on her own, being Deaf. I don’t see her then. I don’t see her having to point to her ears and gesture that she’s Deaf, which she often has to do when people out in the world approach her or greet her or speak to her. I don’t see her getting angry looks from people who said something to her and when she didn’t respond they thought she was being rude; I don’t see her not hearing the PA system on the subway platform, or on the train, or in the store, or everywhere else in the world where the language is not her language and the modality is not her modality.

Up until that conversation in our living room, I’d have said that Deaf people are no more “hearing-impaired” than people who speak Farsi, Finnish, Czech or Vietnamese are “English-impaired.” That’s how ridiculous and wrong it seemed to me when I heard hearing people refer to Deaf people as “hearing-impaired,” identifying them by what they lack, by what they’re not, as opposed to what they have and what they are. And I still feel that way. Of course I do. How else could I love a Deaf woman and make a home with her as equals? But here’s what I now get that maybe I didn’t get before: I think if you asked any monolingual speaker of Farsi, Finnish, Czech or Vietnamese if they wished they could speak and understand English–the biggest bully on the world’s linguistic playground–they would probably say yes. They would probably agree that out there in the world, where English is the lingua franca, life is in many ways easier for a speaker of English.

Of course, it’s not the perfect analogy, because native speakers of other spoken languages can–or can at least try–to learn English. But Deaf people can’t try to become hearing (even though that’s what the so-called experts in the field of Deafness have wanted them to do for the last 200 years). Deaf people don’t hear. It’s not that they can’t hear. It’s that (it’s worth repeating) they don’t hear. So it’s not about ability. Or inability. Or even disability, one might argue. I thought of arguing that now, in our living room, but I knew I would probably get an earful from my lovely Deaf wife and her twin Deaf sister and their acerbic Deaf sidekick. It was three against one. Three Deaf ASL virtuosos against one amateur Deaf wannabe, who had somehow found himself on the wrong side of the argument, and on the far side of the living room. So I inched my chair a little closer to Marlene. And gave her my hand. And held my tongue.

Ω

Paul Hostovsky makes his living in Boston as a sign language interpreter. His poems have won a Pushcart Prize, two Best of the Net Awards, the FutureCycle Poetry Book Prize, and have been featured on Poetry Daily, Verse Daily, and The Writer's Almanac. His newest book of poems is Pitching for the Apostates (forthcoming, Kelsay Books). To read more, visit his website at paulhostovsky.com.

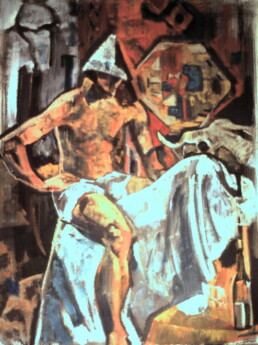

From Mario Loprete (Catanzaro 1968, Graduate of Accademia of Belle Arti, Catanzaro, ITALY): Painting for me is my first love. An important, pure love. Creating a painting, starting from the spasmodic research of a concept with which I want to transmit my message. . . this is the foundation of painting for me. The sculpture is my lover.

My cat's tail

by JEREMY CALDWELL

dangles over the windowsill,

the way a fishing line might wave

in sunlight. But it's too thick

for a fish-line, maybe a rope

for tying a boat to the dock.

On the couch I watch this tail sway

imagining that boat’s rope,

knowing the feeling of being towed:

Alarm dragging me from the bed

into a dusk-set room, my thoughts caught

in the drag of a murky livewell,

and with pen as my pole,

hoping to catch what’s in front of me.

Ω

Jeremy Caldwell's writing has been published in Comstock Review, Work Literary Magazine, Potomac Review, and Prairie Schooner, among others. He received an MA in Creative Writing from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and currently serves as Writing Center Director for Doane University.

J’Atelier9 (@jatelier9) emerged after her Los Angeles-based visionary founder, Janine Tang, began her movement towards a circular environment philosophy by sourcing reclaimed materials into sustainable fine arts. J’Atelier9 reshapes the transcendent beauty of innovative repurposing in her fine arts, allowing her fine art to transform into an unconventional vessel. J’Atelier9 translates the interconnectedness of the world through her works by highlighting society’s sensationalism of media, global discourse, planet preservation, glorification of materialism, technological dependence, natural habitat, fashion lifestyle, relatable human experiences, programming within the matrix, and complex facets of duplicity.

Kung fu

by KATE NOVAK

“Asia! Asia! Hey, Asia!”

The window is open, and Korek’s voice calling my name seems to be pulling at the curtain, which is moving with the dry wind. It’s one of the first hot days of June; soon summer will be here. I just have to pass the last exams at school and the long, warm days will stretch before me like a roll of silk. Even in an eastern European town, on the flat, uninspiring plain, summer still manages to pull off its trick: the beginning of the season is as full of promise here as elsewhere.

“Asia!”

I lean out of the window.

“I’m studying.” There are three of them there. I didn’t expect to see them, especially not Weder. In the sun, his dark hair looks navy-blue. He’s looking at something in the dirt.

“What are you studying for?” Korek asks.

“I’ve a history test tomorrow.”

“You study and study.”

“Not true. I hung out with you guys yesterday.” I rub a tiny wine stain on my t-shirt. I haven’t changed it from last night because it’s my lucky Bruce Lee t-shirt. It helps with studying.

“Yeah, but that was last night. Come out, take a break. We’ll go for a ride.”

“A ride?”

“Garstek has a car.”

Now that’s unheard of. I close my books and I put on my new necklace, the one I made to wear to the party and then forgot to put on. It’ll cover the small red stain. I’m not used to this sweet wine. It made my head swirl. I hadn’t expected it to be pleasant. I go downstairs.

“Where did you get the car?” I ask.

“A friend lent it to me for the afternoon.” Garstek has curly blond hair, the dusty golden shade, and fat lips that always look a bit wet. He blinks his myopic eyes nervously, unsmiling, even when he laughs his forced laugh. Maybe it’s because he’s so ugly that he thinks he’s smarter than everyone else; maybe he really is smart – I haven’t decided yet.

Garstek opens the door of an orange Fiat.

The small Fiat, a.k.a. “maluch,” was the Volkswagen Beetle’s uncool, crude, and poor second cousin, twice removed. But it was still a car: an imagined status symbol and a real object of desire. Maluch was the most common car in an era when cars signaled luxury and wealth; second-world style. Under communism everyone was supposed to be equal, but humans seem to dislike equality instinctively, seeking, yanking out, and obsessing over the tiniest difference to valorize and parade as a sign of superiority. To the untrained eye, those differences were negligible, but communism trained our eyes well. If you had a car – even a maluch, the three-door tin with plastic seats and an engine comparable to that of a coffee grinder – you were a whole class above the rest of us, who walked the earth instead of driving.

“Get to the back seat,” Korek tells me.

“She’s riding in the front. You go to the back,” Garstek says, and Korek obeys, saying nothing. If Garstek is ugly but maybe smart, Korek is neither. His face resembles a potato both in texture and color, and, come to think of it, his head is shaped like a potato as well. If I touched it, I’d expect to find small sprout knobs; but I’d never touch it.

“Move over,” Korek says to Weder, who responds with a distracted, “Hmm?” Garstek pulls down the front seat for me, closes the door behind me, and then gets in.

If I lean over closer to the door, I can see Weder in the side mirror. He’s not looking at anything in particular, and definitely not at me.

“Do I have to wear a seat belt?” I ask.

“You don’t have to,” Garstek says, “but it’s for your own safety.”

“As a matter of fact, more people die in accidents and become crippled for life because of seat belts, but nobody will tell you that,” Korek says.

“Nobody will tell you that, because it’s not true.”

“It is! It’s statistically and scientifically proven.”

“Korek, you’re statistically and scientifically an idiot.”

“Weder, tell him.” In the constant quibbles between Garstek and Korek, Weder is the arbiter, but he responds with his usual, “Hmmm?”

“And where did you hear that, anyway? Like, there was some kind of a study to see if seat belts cause accidents? Like, they thought, oh, we’ve been putting seat belts in cars, but what if they cause more harm, is that it? Did they call you as an expert on this, or did it all happen in this big head of yours?” Garstek knocks on his own head with his fist, which is surprisingly small.

“Watch the road,” Korek says, sulking.

“And what do you think, miss Asia? Do seat belts cause accidents? Do they maul people?”

“Like she would know,” Korek cuts me off. “Besides, I never said they cause accidents. I just said that in accidents they are proven…”

“You are proven to know absolutely nothing of what you’re talking about,” Garstek laughs, and his thick lips glisten with saliva.

If I lean my head against the door, I can pretend to watch the street. Weder is wearing a black t-shirt, maybe the same one he was wearing last night. His black eyebrows are pulled together in concentration as he’s tracing something distractedly on the glass with his finger. His thick black hair is pulled into a ponytail at the nape of his neck. And then he looks in the mirror and smiles at me. He knew I was watching him all along. Korek looks first at him, and then at me. I twist my necklace around my finger: one loop, two loops. I made it out of dry pasta and painted it red and yellow and green. Summer colors, bright and cheerful.

“They are a safety device,” I say.

“Exactly!” Garstek exclaims. “They are there for your safety,” he says it slowly, turning to Korek, stressing each word, like he was talking to an idiot.

“Oh yeah? Did you use a safety device last night?” Korek asks me.

“Don’t be mean,” Garstek says.

“Weder, did she use a safety device?”

“Shut up,” Weder says.

I inch away from the door to avoid meeting his eyes.

“Did you?”

“Change the goddamned subject, Korek.”

We ride along the dusty streets. Soon, the apathetic greenery of the squares will be trampled by the kids, once school finishes. There isn’t anything to comment on. Same streets we’ve known all our lives, same grey dust, same miserable patches of grass.

“What’s Monika up to? Why hasn’t she come with us?” Korek asks. Monika is Weder’s girlfriend. I don’t know the answer, but they surely do. Nobody says anything. I pull at my necklace. One loop around my finger, two loops, three.

“Asia, if Weder proposed to you, would you want to be his wife?”

“Korek, next year she’s finishing high school,” Garstek says. Garstek, Korek and Weder are two years older than me. Garstek is my cousin, and Korek and Weder are his best friends. They all went to primary school together. Up till last year, they ignored me completely, as a child. Whenever Garstek’s back – once every six months or so – we hang out. Garstek studies at a university (maybe he is smart, after all?) in Warsaw, which seems a whole universe away from here, a small town in the south of the country. I’m curious about his life out there, but it seems so strange that I don’t even know what questions to ask. If I get into the university next year, I’ll learn all about it my own way.

“That doesn’t answer my question. If he wanted you to be his wife, would you?”

I turn to look at him reproachfully. My necklace catches on the seatbelt and the thread breaks. Pasta beads spill on my lap and on the floor.

“Oh my god, you would! Did you see that?” He turns to Garstek. “She totally would! Would you like to have his babies?”

“Korek, goddammit…” Garstek says impatiently.

“No, no, let me, because I’m sure that’s something they didn’t discuss in the heat of the moment, did you, Asia? You never told him that you’d like to be his wife, did you? So poor Weder is thinking that he’s just lucky to get laid at a party when Monika is away, while in fact he’s being manipulated into something much, much bigger!”

I don’t know what to do with the colored pasta; it’s staining my hands. They must be getting sweaty. I notice marks of paint on my t-shirt as well. I was planning to wear it tomorrow to school. And now it’s ruined. I roll down the window and chuck out the pasta beads.

“You’re such an idiot,” Garstek says to Korek.

“I think I want to go back.” I turn to Garstek.

“But we haven’t even left the hood,” Korek says.

“Shut up,” Garstek says. He’s not looking at me. He’s watching the road. Suddenly he turns the wheel to take a U-turn. I am pushed against the door, and I see Weder briefly. As the car’s turning, the door flies open. I catch it in a wide, Kung fu-like gesture, and pull it shut. There is silence, and then Garstek bursts out laughing. He laughs and laughs, and then Korek joins him, and then, hesitantly, Weder. They are all laughing till they’re out of breath.

“She could’ve ended up on the street. Imagine if she wasn’t wearing a seat belt,” Korek says.

They drop me off by the entrance to my building. I go upstairs to our flat. I wash my hands in the bathroom, put my t-shirt in the washing hamper. Even if I wash it now, it won’t be dry by tomorrow morning. I go to my room, and I try a karate-chop in front of the mirror. My history textbook lies open beside me, but I don’t feel like reading it. I lie down on my bed.

“Dinner’s ready,” my sister comes to tell me.

“I’m not hungry.”

“Why are you lying here like that?”

“Like what?”

“With just a bra on? Where’s your t-shirt?”

“It got soiled.”

“Soiled?”

“Stained.”

“I told you the pasta necklace was a stupid idea.”

I say nothing.

“Well, if you want to join us, dinner’s ready.”

“You already told me.”

“Whatever.”

She goes out of our room back to the kitchen. The wind is pulling at the curtain. There are distant voices of children, playing with a ball. The evenings are getting longer and warmer. The blue light fills the room slowly, first erasing the sharp edges, then obliterating all. I watch the light square of the window get darker and darker. I try one more pose in front of the mirror, legs wide and bent, one arm behind me, another in front, with fingers outstretched, welcoming whatever comes. I make a Bruce Lee noise, half-squeak, half-scream. Maybe if I use a hairdryer I can wear my lucky t-shirt tomorrow, I’m thinking. I’ve been studying, I know I can probably get an A without it. But I’m going to need a lot of luck later.

Ω

Kate Novak is a feminist, immigrant, vegan cat lady. She writes about what she considers important: being an outsider, speaking from the margins, and representing a minority perspective. She teaches American literature and writing. She is passionately anti-anthropocentric. Kate has published several short stories in online and print magazines, including Fairlight Books, Eunoia, The Bookends Review, Literary Yard, and Literature Today, volume 7. She also writes academic books and papers about literature, culture and translation. She has two novels in preparation, which she hopes to publish one beautiful day.

Ann Calandro is a writer, artist, and classical piano student. Her short stories have been accepted by The Vincent Brothers Review, Gargoyle, Lit Camp, The Fabulist, and The Plentitudes, and other literary journals. Duck Lake Books published her poetry chapbook in 2020. Calandro’s artwork appeared in juried exhibits and in Mayday, Nunum, Bracken, Zoetic Press, Mud Season Review, Stoneboat, and other journals. Shanti Arts published three children's books that she wrote and illustrated. See more of her work at anncalandro.webs.com.

Borges, Keats, & My Aunty

by CANDICE KELSEY

for Gail, d. August 2022

My aunty didn't read poetry. No

real use for it. Give her the Idaho Press,

a grandkid, or a hummingbird feeder. She

lived in verse, rhyme, & metered time.

My aunty couldn’t spot alliteration, assonance,

or consonance. Hand her hot coffee, curlers, & a cold

Diet Coke to go. She’d rev and show her vanity

license plate – EXESSEV.

My aunty didn’t know blank verse from free.

She’d take ESPN or the NHL Channel for her Anaheim

Ducks — then cheer in lyrical, narrative,

& whimsical ballad.

My aunty didn’t read my poems. Her Seventy

stanza life offered conceits to metaphysic

masters; forty-five folios of mothering dissolved any

Augustine nods to human frailty.

Eyes like untitled poems surfacing from eddies

on Lake Powell. Aunty Gail. O my, Chevalier!

Like Borges on reading Keats, you were

the most significant poetic encounter of my life.

Ω

Candice Kelsey [she/her] is a poet, educator, and activist in Georgia. She serves as a creative writing mentor with PEN America's Prison Writing Program; her work appears in West Trestle, Heimat Review, Poet Lore, and Worcester Review among other journals. Recently, Candice was a Best of the Net 2021 finalist and a Best Microfiction 2022 finalist. She is the author of Still I am Pushing (FLP '20), A Poet (ABP '22), a forthcoming full-length collection (Pine Row Press), as well as two forthcoming chapbooks (Drunk Monkeys' Cherry Dress and Fauxmoir Lit). She has five and a half cats. Find her @candice-kelsey-7, @candicekelsey1, and www.candicemkelseypoet.com.

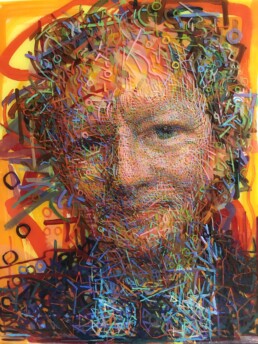

John Hampshire was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1971. He is currently a Professor of Fine Art at the State University of New York Adirondack, where he has taught for the last 18 years. Among other institutions, he has also taught for the Oklahoma Arts Institute. John’s work has been exhibited at such locations as The Show Walls at 1133 Avenue of the Americas in NYC, The Fine Art Gallery at the State College of Florida, The Hunter Gallery in Middleton, Rhode Island, The Brattleboro Museum, and the Project Room at the Phoenix Gallery in NYC. John lives and maintains a studio in the former Church of the Holy Trinity in Troy, New York, and at Cornerstone Studios in NYC.

Dana and the Pretzelman

by ANDREW SNOVER

The Pretzelman died yesterday. He was shot on his corner half a block from his home, and if he has family, they’ll pile stuffed animals, and one of his boys will spray-paint RIP, and someone will take his corner. Old ladies will sometimes mention him, but that will die out as well, and the neighborhood’s memory of him will fade like the colors of the teddy bears’ fur and the sharpness of the letters RIP and the print of the newspaper clipping in its vinyl sleeve stapled to the telephone pole.

Dana knew the Pretzelman. She was a fifteen-year-old girl from up the block. She knew of the Pretzelman before he had the corner, because her eldest brother had fucked the Pretzelman’s cousin for a few months, but the two of them never met until the Pretzelman took the corner and began to make himself known.

He stayed on the corner all day, unlike the men who owned neighboring blocks and took breaks on the hot days to drive around in their cars with their music and air-conditioning blasting, just to make themselves seen. He just walked down in the mornings and stayed there all day, every day. He and his boys would talk to each other, and stare down cars whose drivers they didn’t recognize, and sell to those who bought.

Dana first met him one morning when her grandmother sent her out for a forty of Olde English. It was a hot Sunday, and her grandmother’s favorite treatment for the brutal heat of their home was to drink something cold. The house smelled of death from the time that a great-aunt had declined and passed in the living room. Because the family had no money to keep her in a hospital, and because her bed couldn’t fit up the stairs, for six months she had been in the center of all activity in the house. The stench of her sheets and her disease had slowly permeated everything, and then she had died. Dana liked being sent to the store for forties and half gallons of milk and packs of Newport 100s because it got her out of the smell.

She walked down the street, looking out for any of her friends who might be awake and out on their stoops. She didn’t see anyone as she walked the block, so she crossed diagonally through the Pretzelman’s intersection toward the store that stood on the corner where he usually stood with his friends. The small white awning read, “Complete Grocery and Deli,” and there was a sign that said, “Hoagies Snacks Cigarettes We Appreciate Your Business.”

Dana knew enough to know what groups of boys said to girls walking alone, and she knew that her age was no longer a protection now that her body had changed. That day there were three others besides the Pretzelman. As she walked up to them, and they looked at her flip-flops and her shorts and her beater and her purple bra underneath, she prepared herself to deliver an insulting reply to their comments, but no one said anything. The Pretzelman smiled at her, and she passed through them into the store.

She walked up to the glass, spoke loudly, “Olde E,” to the distorted image of the lady on the other side, passed through the slot the five-dollar bill her grandmother had given her, waited for her change and the brown bag to spin on the carousel to her side, and left. As she passed back through the group, the Pretzelman said, “Have a good day now,” and she didn’t say anything.

That day the heat endured, so Dana was sent back to the store two more times on the same errand, and by the last trip, she had smiled at the Pretzelman. He told her to have a good night.

The Pretzelman lived in an abandoned house around the corner that he and his boys had fixed up a little bit. He said hello to the old ladies. He threw his trash in the can, at least when he was on his corner. Dana wasn’t sure if he made his boys do the same, but there wasn’t much trash on his corner compared with the other three of that intersection, so she thought that he did.

He got a puppy from a man he knew who bred pits. It was a brown-and-white dog with a light nose and light eyes. He walked it on a leash down to his corner in the mornings, and then he tied it to the stop sign, and it stayed with him and his boys. They fed it chips and water ice and other things that they bought from the store. The old ladies sometimes would stop and pet it.

Dana loved dogs, and she asked the Pretzelman one day if she could pet it, and he said, “Of course,” so she petted it and talked to it. After that, on trips for Newports and chips and hug juices, she would always kneel down quickly and whisper in the dog’s ear, “Good pup,” or “I love you.” The Pretzelman would smile down at her, and she would tug on the dog’s ear and then run in and finish her errand. One day as she knelt down to pet it, she looked over at a parked car and she saw a pistol sitting on top of the rear passenger side tire.

She got more comfortable around the Pretzelman through her relationship with the puppy. She asked him one day if she could see his gun. He chuckled and he said, “That stuff isn’t for girls like you,” but when she asked again a few weeks later, he reached into the wheel well and picked it up. He uncocked it and handed it to her. The weight of it frightened her, and she stared at it in her hand, thinking in a haze that it must weigh more than the puppy. She put her finger to the trigger, and the gun was so big that only the tip of her finger could reach around. She stood up and pointed the gun at the Pretzelman, and she heard her own voice say, “What now,” and she saw the Pretzelman’s face drain.

Her hand shook and her knees shook, and the Pretzelman took one step forward and snatched the gun from her hand and slapped her in the face. She didn’t cry out, but she shuddered and cried a few tears and said, “I’m sorry, I don’t like that.” She had scared herself as much as she scared him, and the Pretzelman saw this, and he said, “This ain’t no joke. Why you think I said guns aren’t for girls like you.”

She talked to him a lot about guns after that. They sat on the stoop of the house next to the store, and he told her that most boys held their left arm over their face while they shot with their right because they didn’t want to see what the bullets did. He said that only the crazy ones or the liars said they didn’t cover their face. She asked him if he covered his face, and he didn’t answer for a minute. Then he said, “Not the first time.”

He took her behind his house to shoot the gun, because she asked him if she could try it. They walked through the high nettles and the broken glass and the needles, and he said, “Watch out for dog shit.” He made her stop and then walked ten feet and set a bottle on the back of a chair and came back and handed her the gun and said, “Here.” She pointed the gun at the bottle, and her body jerked, and her ears rang, and the smell made her eyes burn. She looked at him after the first shot, and he said, “Try again, but hurry up ’cause they’ll call the cops.”

She shot six more times and hit the bottle with one of the shots, but she couldn’t tell which one because the cracks and the flashes didn’t match up. The wall behind the bottle was soft quarried stone with lots of mica, and the divots and craters where her bullets hit were a fresher shade of gray than the rest, and they sparkled in the light. She thought through the roaring in her ears that if someone were to shoot the whole house, it would look newer than it did.

She told people about the Pretzelman because she was proud to know him. She told her friends about him and introduced a few of them to him. One Saturday night she had her friend Kiana sleep over, and they whispered about boys until late. “He don’t say anything ignorant to you, and he’s even nice to the old ladies,” Dana said. Kiana rolled her eyes.

“You know he’s too old for you. You wouldn’t even know what to do when he started to try out that nasty shit.”

Dana shrieked and rolled over onto her belly. Then she said, “I would too know what to do. I would too.”

That night after the girls had fallen asleep, they were awoken by a string of gunshots and then tires squealing. When it ended they ran to the windows and looked up and down the block, but they didn’t see anyone. Kiana fell back asleep soon after, and Dana lay there for a long time listening to her steady breathing, thinking about situations that could be, and in them what she would do.

On her way to the bus the next morning at seven, Dana walked past the poppy store and saw the Pretzelman in his normal spot. He nodded to her, and she ducked her head. She felt a quickness in her chest and heard a buzzing in her ears. When she got on the bus, she tried to close her eyes and take a nap like she usually did on the way to school, but she couldn’t find a comfortable position in her seat.

In English class that day, Dana’s teacher talked about how the best characters always seem very real, yet a little too large for life. Dana raised her hand and said, “I know someone like that. He’s got the corner on my block, and he has this nice dog. They call him the Pretzelman because his skin color is like the pretzel part, and that stuff he sell is white like the salt.”

“He sounds like an interesting character,” said the teacher. “I would enjoy reading a story about the Pretzelman.”

After that, Dana couldn’t help but think of the Pretzelman as a character. Everything he did was covered with a thin gauze of fantasy. One of the boys on the block wanted to work for him, but they already had a lookout and the boy was too young for any of the other jobs, so they sent him on little errands. One of these errands was to take the bus to Target and buy sheets, because the Pretzelman was tired of sleeping on a bare mattress. Or at least tired of hearing his girls complain about it. The boy took the hundred dollars he was given and rode the bus for thirty-five minutes and went into Target and bought the sheets. The Pretzelman had said to him, “I don’t need no change, understand?” The boy knew that the change was to be his payment for the errand, but in order to avoid looking like he was trying to profit too much, he bought the most expensive set he could find. He brought back a set of king-size sheets and proudly presented them to the Pretzelman, but they didn’t fit the twin-size mattress. According to Dana, the Pretzelman didn’t make the boy go back to Target and exchange them because the mistake had been his to not give the boy more specific orders. They made fun of the boy and called him King Size, and the Pretzelman slept on a twin-size mattress with sheets for a king. Dana looked at sheets the next time she was in Target, and she saw that the most expensive sheets sold there had a thread count of six hundred and cost $89.99, plus tax.

Another time Dana walked down to the poppy store and came upon the peak of an argument between the Pretzelman and one of his girls. She was standing in the street screaming at him and making motions with her arms like she was throwing something at him. The motion was like a Frisbee, and the girl did it over and over again with each hand, and sometimes with both. But the Pretzelman, like a character in a different movie, was just standing against the wall of the store. He wasn’t looking at the girl, and he wasn’t looking away from her, and it looked to Dana like he hadn’t noticed that there was anyone else there at all.

There was a certain face that the Pretzelman used when he was out on the corner, but this one was different. His normal stern-faced grill would crack sometimes. The corners of his eyes would crinkle up if he caught her spitting or stopping to adjust her belt or her shorts. His eyes would crinkle, and she would know he had watched her the whole time.

This face wasn’t crinkling at all, no matter what the girl screamed about his shithole house and his dirty, grubbing life. Suddenly Dana saw him in the same pose, leaning with his shoulders against the wall and his feet planted, but the vista had changed. The tan car in front of him and the picket fence across the street with its peeling paint were gone, and instead he was at the edge of an enormous, planted field, looking out at the work he had done and the work yet to do. Or he was at the top of a rocky hill, and he was looking down at the river below, at the cattle or the buffalo. Or he was on the balcony of a high-rise, looking past the skyscrapers toward the lower buildings, the row homes, and the narrow streets that he owned. Or he was in the tunnel at an arena, waiting to be introduced over the loudspeakers. Waiting for the roar of the crowd. The girl in the street was still yelling, her hair and her cheeks shaking with rage. He could have been made of stone.

Dana tried to talk to the Pretzelman about how she saw him, what she thought about him. Every time she tried it, her words ran into the obstacle of his eyes on her, the smile starting to play in the corner of his mouth. One time she made it as far as telling him, “You know, you’re nice. Really nice.” She wanted to continue, but she could tell he was making fun of her when he replied, “Well, some people think so. I’m glad you think so.”

In English class, her teacher made the class do a writing exercise called “What everyone knows…/What I know…” Dana continued the first sentence. “What everyone knows about the Pretzelman is his puppy, and his nickname.” She quickly wrote a full page in her looping script, smiling as she pictured his eyes, his hands.

She was still going when the teacher said it was time to begin the second part. She wrote, “But what only I know is that he…”

She stopped writing then, and thought about what would happen if she wrote what she knew—really knew—about the Pretzelman. Or if she told it to him out loud. How would his eyes look if she wrote it—all of it—and then handed this letter to him, rather than turning it in to the teacher? When the class ended, her ellipsis was still open, waiting to be filled with what she knew.

Before long the Pretzelman died, and here’s how it happened. He woke up on his mattress on the floor between the sheets he got by sending his boy on the bus to Target. He grabbed his gun from the floor next to his bed. He put the leash on the dog, and he hollered to the others to get up. He let himself out the back, which is what they always did so that the front could stay boarded up and keep its abandoned look. He walked around to the front of the house. He didn’t carry the dog over the broken glass, as he had done when it was a smaller puppy. He might have waved hello to an old lady. He might have stopped to wait while the dog took a shit.

As he walked down the street, he heard the engine of the car roaring, and he looked up to see why someone was going that fast. He saw clearly the face behind the wheel, and then the tires screeched, and he saw clearly the exact same face in the back seat, before the bright flashes. He went for his gun, but the bullets spun him around and knocked him onto his belly, and his arm and the gun got pinned under his body. The dog ran off. The Pretzelman bled out onto the sidewalk while one of the old ladies called 911, and his boys came out and saw what had happened and they ran off. Dana left her house to catch the bus and saw the cops taping off an area around a body that was covered with a heavy sheet too small for the whole creeping stain. She didn’t know it was the Pretzelman until she came home that afternoon and her friends told her.

As she lay in bed that night, she thought about the dark red color and feared that she might never be able to think about anything else. She searched her feelings, wondering distantly if she was going to cry. She fell asleep thinking, but she slept well. It rained that night and the whole day after, so the stain was gone. The Pretzelman’s mother placed the news clipping of his shooting inside a plastic sleeve and stapled it on the telephone pole, with a note about a reward for evidence leading to the killers. Before long the corner belonged to someone else, and there was a colorful cairn of stuffed animals piled against the fence where he’d lain, and one of the walls nearby read RIP. Dana noticed these things when she walked out to the store or the bus stop, and she passed them again whenever she walked back home.

Ω

Andrew Snover has a BA from Penn State in English with honors with a creative writing emphasis, and is studying to receive his MFA from Drexel University. His work has appeared in Tusculum Review.

Rachel Dziga is an American artist who works in printmaking mediums and teaches plein air workshops in both the Texas hill country and the Tuscan countryside of Italy. She received her MFA in Florence, Italy, for Interdisciplinary Art and has exhibited and participated in international artist workshops. She has also recently been featured in the book Women Makers of Arkansas.

healing factors

by FRANK CARELLINI

i personally get my zen

in the home depot garden

section: wilting bonsai

a split branch and what i grow

in the artificial sun of my room

are healing factors: each day, i soften

my branches, wrap my body in copper.

trunk: stripped, bleached, aged

my plate tilts slightly so that vinegary hoisin

pools in reflections my big eyes look so appetizing

sorrow pressed with green onion into egg-wiped wonton

sealed, and fried, and eaten.

Ω

Sarah Gomez is currently working on a series of paintings focused around one's intrapersonal conflicts with narcissism and how those conflicts lead to a breakdown and loss of self-identity.

The Bagboy

by TRACE CARSON

Standing in the breakfast foods aisle at the grocery store near your mother’s assisted living facility, you look for a box of original Cream of Wheat. Your mother has a small galley kitchen in her unit, and you try to keep it stocked, making trips like this once every two weeks. She doesn’t like to go to the facility’s dining room, although it’s available for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, so the caregiver fixes simple meals. The caregiver texts you when things begin to run low, and you keep a running list.

You eat every meal out and take the opportunity to pick up snacks for yourself. Several bags of salt and vinegar almonds, peanut butter that you’ll eat out of the jar, expensive blocks of cheese, maybe a container of hummus and bag of celery sticks. Just so you have something at home to snack on that doesn’t require dishes, an oven, or even a microwave.

“You idiot,” you say to yourself when you realize you’ve wasted time looking at rows of fleshy-faced Quaker men in white wigs instead of for the faces of smiling Black men in white chef hats. “What defect do I have that makes me unable to look?” You finally find the boxes of “original” between the boxes of “maple brown sugar” and “banana and cream.”

“Okay, do your sevens,” your mom says.

You’re lying on your back on the kitchen floor with your feet flat against the wall next to the pantry door. You scoot your butt to your heels and give a big push with both legs to see how far you can slide on the always clean, slick, shiny vinyl floor. Cool, you think to yourself as you break your old record. Mom is standing over the stove, cooking dinner. She’s making meatloaf, which is not one of your favorites.

The sevens and eights still trip you up, so you concentrate as you scoot your butt to your heels again.

“One times seven is seven; two times seven is fourteen; three times seven is twenty-one.” You get to the tricky part: “Seven times eight is fifty-eight; seven times nine is—”

“What’s seven times eight?”

“Fifty-six. I know that. Seven times nine is sixty-three…”

You know there’ll be a salad and, with meatloaf, mashed potatoes. And some sort of dessert. Homemade chocolate cake is usually on hand. She mixes instant coffee into the homemade icing and it’s delicious. You’ll eat the cake carefully, separating it from the icing, which you save for last. When you’re done the icing will stand firm in an “F,” and you’ll savor each chocolaty bite with the faint coffee taste. On the rare occasions when there’s no “ready” dessert, she makes milkshakes in the blender—chocolate for you and strawberry or vanilla for her.

You continue to scoot, slide, and recite your multiplication tables. Mrs. Butler has your fourth-grade class go to the twelves, which is impressive, you think, because at that point you’re hitting three-digit numbers. Your mom has omitted the ones, twos, fives, tens, and elevens from your nightly practice since they’re now too easy for you. You recite the elevens to yourself because you like the pattern. She opens the pantry door next to you, looking for something on the shelves.

“Go downstairs and get me some celery salt.” You continue to slide. “Now,” she says.

“Okaay-ya,” you say as you get up and trudge down the stairs to the basement.

Half of the basement is finished. You walk into the downstairs den with the brick fireplace that is never used except for your parents’ parties once or twice a year. This is the room where Dr. Moneymaker had the heart attack and died during the Christmas party last year. You walk through your playroom that your grandfather remodeled for you. The walls are wrapped in white paneling with baby-blue-highlighted fake wood grain. The eight-inch floor tiles are white with an embossed geometric design, also in a light blue. Built-in shelves and a long counter run along one side of the room. The room is packed with all sorts of toys, many that you don’t play with any longer. Some you never did.

You turn into the large, unfinished part of the basement with the hard slab floor where the furnace and water tank are hidden in shadow. This part of the basement smells different than the rest of the house. Your father’s desk, a hollow-core door painted in black lacquer, is supported by a two-drawer filing cabinet on either side and covered with stacks and stacks of paper. An old manual typewriter sits on a flimsy aluminum stand to the side. Metal shelves filled with notebooks separate his “office” from the mechanical stuff.

In front of his desk are two rows of two metal racks. Each rack is six feet long and has five shelves. You’re not tall enough to reach the top shelf yet. They’re stocked with non-perishables: cans upon cans, boxes of different mixes, flour, sugar, condiments, spices, pie tins, Saran Wrap, Reynolds Wrap, and Mason jars of tomatoes, pickles, and green beans that your mom canned. It looks like a mini-grocery store. A playmate once asked why there’s so much food. You shrugged your shoulders, never having thought about it before.

You look for celery salt. You know it’s going to be with the spices. You see the big, cylindrical, blue container of Morton’s Salt with the girl holding the yellow umbrella. You had asked your mother about the slogan, When it rains, it pours. She told you it means the salt won’t clump in humidity. You see the McCormick’s pepper in the red-and-white rectangular tin. You see Mrs. Dash’s lemon-pepper with the yellow cap that your mother loves to cook with in the more familiar-shaped spice bottle. You scan each of the glass containers, reading the names off. But you don’t see celery salt. A sense of dread overcomes you. You walk back upstairs, head low, knowing she’s going to send you down again.

“I can’t find it.”

“It’s on the third shelf along the back wall, the one in the corner,” she says with a sigh.

You go back down.

“Look, look,” you say to yourself.

You stand frozen, eyes glazed, looking from jar to jar. There’re dozens of them.

“Do you see it?” your mother says loudly. She’s in the kitchen, directly above your head.

“Not yet,” you yell back up.

“Keep looking.”

You stand. “Look!” you say to yourself over and over.

And then, as if with a divining rod, you slide two bottles of onion salt aside, certain to reveal the celery salt. Your heart sinks when you see it’s garlic powder. Then you notice it, staring right at you from the front row. Relief overwhelms you. You didn’t realize your body was so tense. You grab the bottle, and it falls on the concrete slab, unbroken. You take it upstairs.

“Thank you, honey,” your mom says as you hand it to her. “I knew you could find it.”

You’re checked out and leading the bagboy, who’s pushing the grocery cart, to your silver Audi. It’s a late-model, two-door, sporty thing in silver with a powerful engine. You don’t often have need for a car, but when you do, you want something fun and zippy to drive. The trip to your mother’s is not enjoyable with the traffic and congestion on 395. But on the occasions when you take scenic rides to clear your head, on open highways, your Audi makes you feel like you’re on the Autobahn. Shifting on the twists and turns up and down Skyline Drive, it’s as if you’re driving in Monaco’s Formula One race.

There’re not that many groceries, and you could carry them yourself, but the Mongoloid bagboy was determined. You’ve noticed that grocery stores have all but done away with the sensible paper bags with handles. What could have fit nicely into two paper bags are now in nine small plastic ones, some with just two items. You asked the bagboy—who is, in fact, an adult—for paper, but he’s talking about his favorite football team, the Patriots, and isn’t listening to you.

You realize “Mongoloid” and “bagboy” are both incorrect. “Person with Down syndrome” would be the politically correct phrase. Or is it? you wonder. Is that what we’re supposed to call them? Or just mentally challenged? Your daughters would tell you, but they haven’t spoken to you for three years. Only someone with his condition, you think, could get away with wearing a Brady jersey under his green, store-issued vest in a town of die-hard Redskin fans, no matter what their record. Then you think about all the hoopla around the name “Redskins.” That’ll change one day soon. Your mind wanders, and you ponder “bagboy” versus “bagman.” Bagman connotes something completely different. Why the fuck am I thinking about this crap?

So, against your better judgement, you lead the mentally challenged bagman, with your nine small plastic bags, to your car. You pop the trunk and he begins to unload them, two at a time. With each flimsy, formless bag he puts down, items spill out. As you put a pint of Half-and-Half back into a bag and loop the top in a knot, he drops the bag with the carton of eggs onto the asphalt. Globs of yellow-golden yolk ooze between the two halves of the carton, which landed upside down but managed not to open.

“Goddamnit!” you utter under your breath.

“U’m sawwy, u’m sawwy,” the bagboy says as he scoops up yolk with his hands. There’s yolk on the can of green beans, the only other item in the bag.

Ω

Trace Carson was born in Washington, D.C., and grew up in Arlington, Virginia. He received an undergraduate degree in business from the University of Virginia. He enjoys oil painting—landscapes and abstracts—and during Covid enrolled in three semesters of an online fiction writing class through the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, where he experimented with short stories. He has lived in Richmond, Virginia, for 35 years, and has two adult daughters, one of whom recently published a book of poetry.

Renee Samuels was born in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, and grew up in Waltham, Massachusetts. After studying English literature, communications, and art at Boston University, Samuels moved to Woodstock, New York, in 1987, and studied drawing, painting, and art history with Nicholas Buhalis for five years. Samuels has exhibited her paintings, drawings, prints and collages since 1988 in solo and group shows in the Hudson Valley, New York City, Albany and Cambridge, Massachusetts. Aside from making art, Samuels enjoy bike-riding, walking, reading, and Cape Cod.

Privacy

by JOSH PARISH

today a moth

was in my hat

when I put it on

my summer straw hat,

wherein I pretend I'm Don Quixote,

especially on an August afternoon.

When the world outside tilts to the sun,

the world under my hat

is cool and dim

and occupied by me alone,

usually, but today this tickle,

this frightened telegraph in my hair,

this white moth,

who, escaping, hovered

eye to eye, as if to say

it was me who disturbed him,

wings thinner than this page

and really not white

but more like gray ash on snow

Ω

Josh Parish's writing has appeared in or is forthcoming from Rattle, The Pinch, Tupelo Quarterly, Hippocampus, and elsewhere. He received an MFA in fiction writing from the University of Washington, where his collection of short stories, Hardest Weather in the World, won the David Guterson Award. He teaches English at TCC.

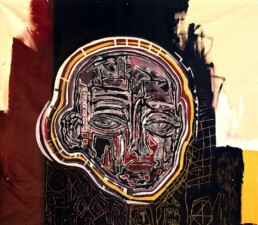

Bennie Herron’s creative output in poetry, painting, and social advocacy reflects on the often-paradoxical conditions of being. His poetry presents a prismatic lens on his upbringing as a Black man, including close observations of the familial, interpersonal, and cultural forces that have shaped him. In these poems, the anecdotal may expand into ruminations on Biblical passages, or tales of the trials and joys of his adolescence may give way to fiery indictments of systemic problems such as racism, colonialism, and the perceptions of Black men in society. Herron’s verse style is informed in part by the socially conscious Hip Hop artists of the 1990s and poets of the Black Arts Movement of the late 1960s, among a myriad of other sources.