Art - Selected Works from TCC & Beyond

Art - Selected Works from TCC & Beyond

Art - Student Contest Winners

Art - Student Contest Winners

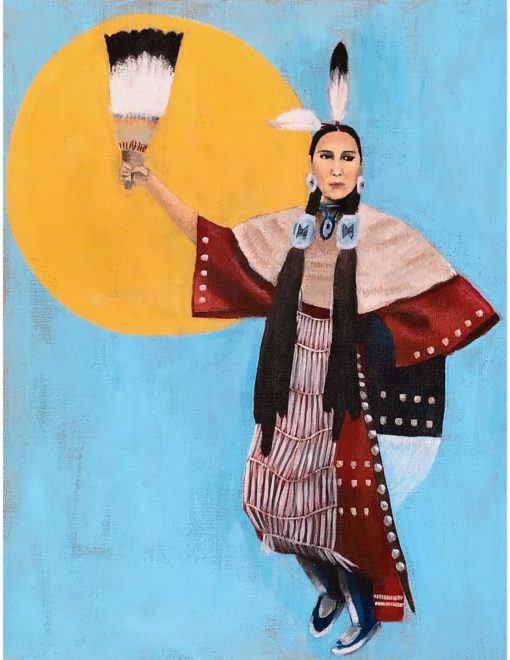

'Red Dress' by Janae Grass

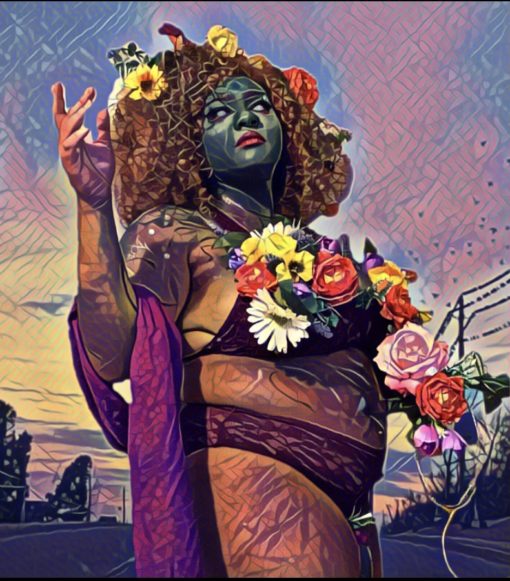

'Untitled' by Daija White

'Untitled' by Tyanna Reed

Girl Scouts of Many Colors

Girls Scouts of Many Colors

by Stephanie Sixkiller

a play in one act

GIRL SCOUTS OF MANY

COLORS Character List

MAGGIE ALBRIGHT: 16, Female. A typical do-gooder. She knows

nothing but how to follow the rules and often takes things way too seriously.

She is always in a tiff with Piper, who she’s gone to school with for as long

as she can remember. However, she doesn’t actively seek to get rid of Piper.

PIPER DONOVAN: 16, Female. What more could you want from an

alternative, sarcastic, angsty teen? She dresses like she has a constant storm

cloud looming over her, and she loves playing practical jokes on people to gain

attention. Everyone else pushes her away except Maggie.

CUSTOMER: Age and gender neutral. Just an average person

that unfortunately gets caught in the crossfire of Maggie and Piper’s antics.

AUDREY SERENA LOUISE URSULA TURNER-TAYMORE: Female. Around

the same age as Maggie and Piper. Although she has no dialogue, it’s obvious

from her appearance that she’s prissy, stuck up, and always gets her way. This

is different from Maggie because she works hard on everything she does, whereas

Audrey probably cheated her way to the top.

Synopsis

Maggie has the whole front entrance of the

Country Mart reserved for the day to sell cookies. What she doesn’t know is

Piper has been plotting to rain on Maggie’s parade.

(Lights up on a table set up for a girl scout cookie

display. There are rows of different types of cookies splayed out very

intricately, and there is a sign taped to the table reading “Help Maggie reach

her goal!” with a meter drawn next to it, filled almost full. Maggie enters,

dressed in a white button down, pleated skirt, knee high socks, keds (or

something similar). It would help to have the beret and sash but it isn’t

necessary. She is looking around her table, checking to make sure everything is

in perfect order. What she doesn’t see is Piper peaking around a curtain upstage,

spying on her.)

MAGGIE

(Sighs in

frustration) Cash box…

(She exits in a

hurry to get her cash box. Piper leans out further from the curtain to make

sure she’s gone before she enters fully. She is dressed in all dark colors

(looks similar to Wednesday Addams or Lydia Deets) and has a large tote bag

slung across her shoulder. She stalks over to Maggie’s table and begins to take

boxes of cookies and place them into her bag. Maggie enters holding a cash box.

She stops dead in her tracks when she sees Piper.)

MAGGIE

Piper Donavon! What in

the world are you doing?!

PIPER

What does it look

like?

MAGGIE

It sure looks like

you’re stealing my cookies!

PIPER

Yep! I’m starving.

MAGGIE

Well, I sure hope you

plan to pay for those cookies.

PIPER

I’m not sure that’s

how stealing works…

MAGGIE

Would you mind

putting them back, Piper?

PIPER

(Mocking) But

then you’ll win the contest… And where’s the fun in that?

MAGGIE

Just because you’re

bitter that you got disqualified for lacing your cookies with laxatives doesn’t

mean you can ruin my chances at winning the top prize.

PIPER

(Scornfully: Slowly

sets the stolen cookies back on the table. They should be blocked so Maggie

crosses in front of the table during Piper’s monologue so she has a chance to

tamper with Maggie’s cash box.) Oh drats. You’re so right. I’ll never even

have a chance to be as great as the perfect Maggie Albright! Ever since

kindergarten, I knew you were just miles above me. I would have never come

close to selling 500 boxes of precious cookies. What’s the point of even being

a girl scout anymore? I don’t serve a purpose as long as I breath the same air

as Margaret Albright.

MAGGIE

Are you done? You’re drawing customers away.

PIPER

Yep, all done. Sorry

for bothering you.

MAGGIE

Nothing I’m not used

to.

PIPER

Toodle-lo!

(Piper exits with a smirk on her face.

Maggie takes a beat to regain her composure before a possible customer enters

center stage. Maggie catches them off guard.)

MAGGIE

Hello! Would you be

interested in buying some girl scout cookies? It will support troop 863 and

help me on my journey to sell 500 boxes of girl scout cookies!

CUSTOMER

Uh, sure.

MAGGIE

Great!

(The customer

moves closer to Maggie’s table and pauses for a brief moment to decide. They

finally pick up a box and give it to Maggie.)

CUSTOMER

I think I’ll take

these.

MAGGIE

Awesome! That’ll be

five dollars.

(The customer nods

and fishes in their pocket before pulling out a five-dollar bill. They give it

to Maggie, who opens her cash box to put the money inside. Piper is seen poking

her head back out from a different curtain. Maggie quickly pulls her hand back

and shrieks.)

CUSTOMER

Are you ok?

MAGGIE

Fine. Just fine. (Hands

over the box of cookies.) Thank you for your service. Have a nice day!

(The customer

uncomfortably exits, dovetailed with Piper entering, laughing up a storm.)

PIPER

Oh my—oh my GOD, that—that

was priceless!

MAGGIE

(Still shaken up.)

Really? Of all things, you just had to put a dead rat in my cash box.

PIPER

If I can’t steal your

cookies, it’s the least I could do to support your cause. And it’s fake, so

don’t get your panties in a bunch.

MAGGIE

You’re evil.

PIPER

I try.

MAGGIE

Why are you doing

this?

PIPER

Well, for one, since

I got disqualified, I have a lot of free time. Two, your face alone was

completely worth it. Three—

(The customer enters

again, crossing their legs and stumbling up to Maggie’s table.)

CUSTOMER

Ok, kid, I want my

money back!

MAGGIE

What’s wrong?

CUSTOMER

What’s wrong?! (scoffs) You put something in these cookies! I opened

them on the way home and not ten minutes later, I needed to take the longest bathroom

break of my life! I didn’t know I needed to buy a porta-potty to eat a box of

cookies!

MAGGIE

Oh, I—I’m so sorry!

(Fumbles to open

the cash box and jolts before pulling the rat out by the tail and throwing it

behind her. Piper should be wheezing by now, as she’s been laughing during this

entire exchange. Maggie gives the customer their money back and they exit in a

huff.)

MAGGIE

Seriously?

PIPER

(Still laughing) Y-yeah!

MAGGIE

What is wrong with

you?! This is worse than the time you threw my cleats over the telephone wire.

PIPER

Chill, would you?

Freaking buzzkill.

MAGGIE

(At her wits end) You

don’t get it, do you? We’re not kids anymore, Piper. It’s time to grow up. Not

everything is going to be fun and games. (pause) Now tell me honestly.

Why are you always out to get me? What have I done to you?

PIPER

Maybe I just want a

friend…

MAGGIE

What?

PIPER

God, you’re dense. (Sigh) Haven’t you noticed that no one else talks to

me? Ever? In scouts, at school, at home, nothing. No one gives me the time of

day because I look like the physical embodiment of death. And, yeah, I keep

coming back to you because your reactions are the best part of my day. But

whether you want to admit it or not, I think you like having me around too.

MAGGIE

(Trying to hide

her smile) Why didn’t you tell me sooner? Here I am thinking I’ve been

doomed to have a permanent storm cloud follow me for eternity. But maybe

there’s a rainbow hidden in there?

PIPER

Wow, that’s how you talk to people? Anyway, I kind of have a rough time communicating,

seeing as I try to send messages through fake rats and laxatives.

MAGGIE

Yeah, yeah. I get it.

PIPER

For what it’s worth,

I’m sorry. Some of that was too far. (beat) I’ll let you get back to

selling your easy bake cookies.

(Audrey crosses through

with an empty wagon and giant first place ribbon. She smirks and waves at Maggie

and Piper, who are both in shock.)

MAGGIE

I can’t—I can’t

believe she won.

PIPER

I can. It’s Audrey Serena Louise Ursula Turner-Taymore. Her mom’s the freakin’

den mother. I just feel bad for the people who bought cookies from her…

MAGGIE

What did you do—Piper!

PIPER

I bought those laxatives

in bulk. I had to get rid of ‘em somehow. (Notices Maggie is still somewhat

peeved.) You ok?

MAGGIE

You know what? I

think I am.

PIPER

That’s surprising.

MAGGIE

If your antics taught

me anything, it’s not to take things so seriously.

PIPER

Thanks for the moral, mother goose.

MAGGIE

Just shut up, would

you? I’m trying to wrap this up in a nice bow. Now help me pack up, and we can

frolic off into the sunset.

PIPER

Holy friendship,

Batman!

(Maggie groans

obnoxiously, and they begin to take down the table as lights fade.)

CURTAIN

GIRL SCOUTS OF MANY

COLORS Property List

- Boxes of Girl Scout Cookies

- Sign for Table

- Cash Box

- Tote Bag

- Fake Rat

- Five Dollar Bill

- Wagon

- Prize Ribbon

GIRL SCOUTS OF MANY

COLORS Set Dressing

- Folding Table

The War Chest

The War Chest

by Mark FrankT

Cast of Characters

Doi: 12, a little girl.

Nazi German soldier

Grandmother of Doi.

Various Jewish women-prisoners in a Nazi concentration camp during the

Holocaust

Adolph Hitler: German dictator during World War II

The Time/Place:

The action starts out in an attic of an old house, then propels

backwards in time to Europe during the Holocaust.

SETTING: An

old dark attic of a house. The attic is empty except for an old war chest covered with a tarp. A door is upstage

right. The set should be nothing but the door and the war chest center stage.

AT RISE: A young girl, Doi, enters the attic. She is

holding a framed picture of her grandfather. As she opens the door, light

floods the room, illuminating the covered war chest. She is hesitant at first

whether to proceed in the room any farther. A voice is heard in the background.

It is Doi’s.

GRANDMOTHER:

(Grandmother yells for Doi offstage, with a thick German accent.)

Doi, hurry up and put that picture in the attic. Don't dawdle. We'll be

late for Grandpa's funeral.

(Doi starts to leave but is intrigued

by the object underneath the old tarp in the center of the attic. She

approaches the tarp slowly. She puts the picture on the floor. It should face

the audience. She takes the tarp off the chest. On the war chest is a German

swastika. She looks back at the door. She slowly opens the war chest, and a

stream of video of World War II and the Jewish Holocaust engulfs the stage.

This video will play through-out the play. As the video plays, she starts to

cry. She puts her hands over her eyes

and falls forward into the chest as it closes. The lights go black for five

seconds. When the lights come back up, Doi is standing in front of the war

chest with her hands still over her eyes. She slowly removes her hands and

finds herself in line with another woman dressed in a prison uniform. She has a

Star of David armband on. She quickly puts one on Doi, who is confused. The

woman tries to get Doi to be quiet and stand in line. A German soldier enters.

He looks like the picture of the grandfather. Doi runs to hug him, yelling

"Grandpa!” "Grandpa!" The

soldier pulls her off of him and throws her to the ground. He points a German

Lugar at her head ready to fire. He yells something in German. The woman from

the line speaking in German pleads for Doi’s life. The woman is shot in the

head. The soldier stares at Doi, who is in shock. The soldier leaves as Doi

stares at the dead woman. Doi starts to wander and finds a coin. She receives

some soup and bread from a German soldier who laughs at her as he takes her

coin and exits. Before she can begin to eat, a woman pushes Doi down and steals

her food. Doi starts to cry. The German soldier returns. He pulls out documents

from his pocket. The German soldier violently escorts Doi into a room. A man is

seated at a desk facing away from them. He turns around in his chair; it is

Adolph Hitler. He sits silently for a while. The German soldier stands and

salutes him. The soldier gives Hitler the documents. He looks them over and

screams in German at the soldier, who pleads for his life. There is a long,

silent pause as Hitler studies Doi.

Hitler makes a gesture, and the soldier escorts Doi into another room

where there are partial remains of dead bodies stacked next to a crematorium in

a heap. The German soldier gives Doi a shovel, opens the crematorium, and

instructs Doi to remove the ashes. A

woman enters, and the soldier starts to kiss and maul her in front of Doi. He then breaks the woman’s neck as she falls

to the floor. He prepares her body for the crematorium. Doi starts to scream

and runs away. She has picked up the soldier’s gun. Machine gun fire and

soldiers are heard around her. We hear one of Hitler’s famous speeches. Doi

runs back into Hitler’s office. She stares at him, then points the gun at him.

He kneels next to her, and she looks in his eyes. There is a long pause between

the two. Hitler begins to laugh and

grabs the gun out of Doi’s hands. He studies her, removes the Star of David

from her arm, and replaces it with a German swastika. He looks at her with a hard

stare. She begins to cry and puts her hands over her eyes. The lights fade for

a moment, and when she removes her hands she is back in her attic. Classical

music starts to play in the background. The video still engulfs the room. Doi

still has the German swastika on her arm. She hears her Grandmother call for

her. She takes her Grandfather's picture out of the frame. She stares at it for

a long time and then rips it up. She gathers the pieces and stares at them. She

takes a deep breath and starts to cry. Grandmother enters. She runs to Doi and

holds her. She looks around the room at the video engulfing them both. She sees

the ripped photo of her husband in Doi’s hand. She slowly takes it out of her

hand and puts it into the war chest. She then gently takes the swastika armband

off of Doi and places it into the war chest. She hugs Doi again and shuts the

war chest as the video fades out. The only light is from the open door upstage.

Grandmother puts the tarp over the war chest as Doi helps. She grabs Doi’s hand,

and they walk out of the room. Grandmother and Doi turn around and look one

last time at the war chest. They look at each other, trying to read each

other’s thoughts. Grandmother hugs Doi, then closes the door slowly as the

lights and music fade out, and the play ends.)

Who's There?

Who's There?

by Joseph Mills

CAST: GUARDS, at least six, but as many as possible or

desired. GUARD 1 and GUARD 2 wear similar uniforms. The other guards wear

uniforms from different countries, eras, and wars. Each time a guard enters and

says, “Who’s There?” it startles those on stage.

GUARD 1 on stage. GUARD 2

enters.

GUARD 2

Who’s

there?

GUARD 1

What?

GUARD 2

Who’s

there?

GUARD 1

No.

GUARD 2

No?

GUARD 1

No. You

don’t approach the guard on duty and say, “Who’s there?” The guard on duty

says, “Who’s there?” Otherwise, it doesn’t make any sense, and--I’m the guard

on duty.

GUARD 2

Oh,

okay. Sorry.

GUARD 2 exits, then re-enters.

GUARD 1

Well?

GUARD 2

You

told me I wasn’t supposed to say anything.

GUARD 1

Not

“Who’s there?” but you could say something.

GUARD 2

Shouldn’t

you go first?

GUARD 1

Don’t

be petty.

GUARD 2

No,

really, I think it should be up to you.

GUARD 1

Fine.

Who’s there?

GUARD 2

It’s

too late for that. You’ve seen me. You know who’s there.

GUARD 2 exits and re-enters.

GUARD 1

Who’s

there?

GUARD 2

Me.

GUARD 1

Okay,

then.

They relax

GUARD 2

Anything

to report?

GUARD 1

I might

be getting a cold.

GUARD 2

Has

anything happened?

GUARD 1

Like

what?

GUARD 2

Any

ghosts?

GUARD 1

What?

GUARD 2

Ghosts.

GUARD 1

Of

course not. Is that a joke?

GUARD 2

I heard

sometimes you see a ghost.

GUARD 1

Who

said that? Nick? Because he is always slagging me off.

GUARD 2

I

didn’t mean “you” specifically. I just meant people like us.

GUARD 1

Like

us?

GUARD 2

It

doesn’t matter.

GUARD 1

No, no

ghosts. No goblins. No witches. It’s been boring. Because that’s the job. It’s

boring, boring, boring, then maybe Aiiieee! Alert! Then boring, boring, boring.

GUARD 2

Alert?

Because of a ghost?

GUARD 1

No.

It’s someone having a heart attack or, more likely, just thinking they’re having

a heart attack. Or someone pulling the fire alarm. Or people coming up

unexpectedly and not knowing the password. Drunks usually. It’s never ghosts.

GUARD 2

Password?

GUARD 1

Did you

say the password?

GUARD 2

I don’t

think so.

GUARD 1

Do you

know it?

GUARD 2

Of

course.

GUARD 1

Good.

GUARD 2

What

are you going to do now?

GUARD 1

The

usual. Have a drink. Watch something.

GUARD 2

What

are you watching lately?

GUARD 1

The

woman across the street is having an affair. Her husband’s brother, I think.

GUARD 2

I heard

Hamlet is back.

GUARD 1

So?

GUARD 2

I don’t

know. People are interested.

GUARD 1

People

are idiots. They sit around gossiping about people who are famous just for

being famous. Who cares? It doesn’t mean anything. Hamlet’s back because he was

bored wherever he was …

GUARD 2

College.

GUARD 1

… and pretty

soon he’ll get bored here, and then he’ll go somewhere else. It’s what rich

people do. And everyone talks about it as if it’s news. “Hamlet’s here.

Hamlet’s there.” Who gives a shit?

GUARD 2

You

don’t like Hamlet?

GUARD 1

I don’t

like everyone talking about him like he’s important. What’s he ever done? Won a

battle? Built something? Written a play? He’s useless. All that royalty is

useless. They should be taken out back and – Bam! – in the head.

GUARD 2

Then

you’d be out of a job.

GUARD 1

There’s

always people and things to guard. You like Hamlet?

GUARD 2

I was

just making conversation. I’m just kind of hoping you’ll hang out for a bit.

GUARD 1

Why?

GUARD 2

It

makes it easier, having someone else here.

GUARD 1

It’s

not supposed to be easy.

GUARD 2

Less

boring.

GUARD 1

That’s

the job: being bored. You should be glad you’re bored. It means you have a job.

You get paid to be bored.

GUARD 2

Unemployed

people are bored. But I get your point. I should be glad that I’m bored because

it means no one is attacking.

GUARD 1

Attackers?

Ghosts? Where do you get these things?

GUARD 3 enters.

GUARD 3

Who’s

there?

GUARD 1

What

are you doing?

GUARD 3

I was

bored. What are you guys doing?

GUARD 2

Just

hanging out.

GUARD 1

Working.

GUARD 3

Cool.

Hey, did you hear...?

GUARD 1

You

don’t need me, then.

GUARD 2

Don’t

go.

Enter GUARD 4 and GUARD 5.

GUARD 4

Who’s

there?

GUARD 1

What

the hell? Is that the password today?

GUARD 5

We

heard noises. We thought something was going on.

GUARD 1

You

didn’t bring any weapons.

GUARD 4

They’re

heavy.

GUARD 5

And

kind of awkward. We thought we’d check out what’s happening, and we could go

back and get them if we needed them.

GUARD 4

You

having a party?

GUARD 1

We’re

working.

GUARD 2

But

you’re welcome to stay.

GUARD 5

Anything

to drink?

GUARD 2

Not

yet.

GUARD 1

Not

yet? Go back to bed.

GUARD 5

Alone?

GUARD 6 and more guards, perhaps

many more guards, enter.

GUARD 6

Who’s

there?

GUARD 1

Oh, for

God’s sake. Go home, everybody. Go get something to eat. Go to (name of local bar). Go back to doing

whatever you were doing.

GUARD 3

That

was boring.

GUARD 1

This is

boring.

GUARD 4

Not as

boring.

GUARD 5

Something

might happen.

GUARD 1

Nothing

is going to happen.

GUARD 3

It

might.

House lights come up

GUARD 5

See.

That’s something.

GUARD 1 looks at audience

GUARD 1

Oh,

God’s blood, not more of you. Let me guess. You were bored. Go home. Go back to

bed. Go back to someone else’s bed. There’s nothing here for you. Nothing’s

going to happen. Anything that would have happened would have happened by now.

GUARD 3

Then

why are you guarding?

GUARD 1

It’s a

paycheck.

GUARD 2

And

just in case.

GUARD 3

There

you go.

GUARD 1

Well,

nothing can happen while you’re all here. Get out of here and maybe it will.

GUARD 5

I think that’s exactly wrong. Look at all of us. We wouldn’t all be here if there wasn’t a

reason. There are too many of us here for nothing to happen. Maybe . . . maybe

. . . we are the something. Maybe we are what’s happening.

GUARD 1

That is

nicely narcissistic. Seriously, everyone get out of here.

GUARD 1 gestures for the

houselights to come down.

GUARD 4

You’ll

tell us if something starts to happen?

GUARD 1

Yes.

GUARD 4

Promise?

GUARD 1

If

something happens, I’ll call.

GUARD 3

Wait,

you’re not even the guard on duty now.

GUARD 2

I’ll

call.

GUARD 3

Promise?

GUARD 2

Yes.

GUARD 3

Can I

just leave my stuff so I don’t have to bring it back later?

GUARD 1

No.

Everyone take your stuff. All of it.

Everyone leaves but GUARD 1 and

GUARD 2.

GUARD 2

I don’t

think any of them knew the password.

GUARD 1

Probably

not.

GUARD 2

Do you?

GUARD 1

Of

course. Don’t you?

GUARD 2

Yeah.

GUARD 1 seems about to go.

You

said you were going to hang out for a bit.

GUARD 1 hesitates.

It’s

supposed to be cold tomorrow. See any good bear-baiting lately?

Pause.

I heard

Hamlet got Ophelia knocked up.

GUARD 1

It

happens. What are they going to do?

GUARD 2

I don’t

know, but here’s what I heard …

(dark)

The Elevator

The Elevator

by Cameron Cox

Characters:

Lance Phillips: Main Protagonist. Early 30s’, blonde hair,

and clean shaven. He is the vice president of software at an unnamed

corporation. He commits industrial espionage for a rival company and becomes

haunted by a monster that looks just like him but in a distorted, computerized

form.

Computer Lance: Main Antagonist. He is a distorted,

computerized version of Lance. He confronts Lance and warns him of the dangers

that he has brought upon himself and those he cares about. He is also

transparent, as nothing physical can touch or hurt him.

Chelsea: Lance’s unseen fiancé. She and Lance are planning

on getting married.

Cliff: Another unseen character. He is the man that Lance

plans to sell the files of his workplace to for a lump sum of money.

fade in:

EXT. – WORK BUILDING – UNNAMED CITY – EVENING

ZOOM IN on the work building. It’s a big building.

cut to:

int. – work floor

We see that the work floor is empty of people and few lights

are around the floor. We cross over to the outside of an office. On the blinded

window, we see the words “Lance Phillips, Vice President of Software.”

cut to:

int. – lance’s office

Inside, we see Lance Phillips himself. He sits in front of

his computer, typing and clicking really quickly as he sweats. He is committing

industrial espionage.

A window pops up on his computer that says, “transfer

files?”

Lance slowly moves his mouse over as he adjusts his collar.

He clicks the yes button and the transfer process begins.

As he waits for the loading process, his phone goes off. He

looks at it and sees that his fiancé, Chelsea, is calling him. He picks up the

phone and answers.

lance

Hi, babe.

chelsea (v.o.)

Lance, where are you? I’m at the wedding venue.

lance

(nervous)

Oh, uh… I’m just finishing some stuff up at work. It’s been

real crazy today.

Lance looks at his computer and sees that the loading

process is almost complete.

CHELSEA (v.o.)

(suspicious)

Are you ok, Lance? You sound like you’re up to something.

lance

No! No, of course not.

Lance gets another call. He looks at it and sees that it’s

from someone named Cliff.

lance (cont’d)

Chelsea, I’ll be there in about 15 minutes. Bye.

Lance hangs up on Chelsea and answers Cliff.

CLIFF (V.O.)

Do you have them?

lance

Yes, sir. Files are all downloaded.

Lance goes over to the computer. There is a window that

says, “All files downloaded.” Lance takes a flash drive out of his hard drive

and puts it in his suitcase.

cliff (v.o.)

Good. Meet me outside the building and we’ll make the

exchange.

lance

(nervous)

What if I get caught? I mean, if my people find out what I’ve

done, I—

cliff (v.o.)

Will you shut up about that? You won’t get caught unless you

talk. Look, they’re not paying what you deserve, right?

lance

Right.

cliff (v.o.)

Exactly! Now, you do this, and you will be paid what’s yours.

lance

Of course.

Lance hangs up his phone and shuts off his computer. He

grabs his jacket and suitcase and walks out the door.

int. – work floor

Lance walks across the work floor and towards the elevator. He

presses the button and waits.

computer lance (v.o.)

Where are you going?

Lance looks around.

lance

Hello?

No one responds. He shrugs it off and continues to wait.

LANCE

(impatient)

Come on already!

computer lance (v.o.)

Where are you going?

Lance looks around the work floor to see where the voices

are coming from. He sees no one nor any source of noise.

LANCE

Okay, whoever’s around, knock it off!

One of the overhead lights starts to flicker, which catches

Lance’s attention. Suddenly, more of the lights start to flicker, which begins

to make Lance nervous.

computer lance (v.o.)

(sounds closer)

You can’t escape.

Lance becomes frightened and rushes back to the elevator. He

sees that the numbers have not changed. The lights flicker more, and Lance

quickly heads for the stairs.

int. – stairwell

Lance enters the stairwell and runs really quickly down the

stairs. He keeps rushing down the stairs for a few moments as the voices

continue to taunt him.

computer lance (v.o.)

You can run, but you can’t hide.

lance

SHUT UP!!!

Lance eventually finds a door and bursts through it.

INT. – WORK FLOOR

Lance starts to loosen up as he looks around the floor. He

seems rather familiar with the floors.

Lance walks around the floor and sees the outside of his own

office.

lance

(shocked)

No! It can’t be! I just ran down 20 flights of fucking

stairs!

computer lance (v.o.)

Unbelievable, isn’t it?

lance

Okay, what’s going on here?! Who are you?! Where are you?!

What are you and what do you want?!

computer lance (v.o.)

I am a monster, and you are my creator.

lance

(in denial)

This isn’t real! It can’t be!

computer lance (v.o.)

(taunting)

Oh, but it is indeed.

lance

SHUT THE FUCK UP!!!

Lance goes back to the stairwell.

int. – stairwell

Lance runs down the stairwell again. After a few flights of

stairs, Lance comes across a drop. He nearly falls but manages to keep his

balance. He turns around and sees the stairs behind him are completely gone.

computer lance (v.o.)

Nowhere to go but down.

Lance looks to his side and sees a door. He bursts through

it where he ends up in…

int. – dark hallway

Lance calms down a little.

lance

Thank God that’s over.

The sound of a ding goes off. Lance looks down the hallway

and sees an elevator at the end.

Lance walks slowly to the elevator and wonders who could be

inside. The elevator opens, and out walks a man who looks like a distorted,

digital image on a computer. As the digitized man comes closer, Lance realizes

the man is a digitized version of himself. This is Computer Lance.

computer lance

Why, hello there, Lance.

lance

Who are you? What do you want from me?

computer lance

Like I said, I’m a monster, and you are my creator.

lance

(in denial)

This isn’t real. You’re not real.

computer lance

Right, and you committing industrial espionage wasn’t real.

lance

What are you talking about?

computer lance

Don’t play denial with me, Lance. I saw you. Tell me, what

kind of a man in a high position with a good life steals from his own place of

employment?

Lance stays silent as he shakes with fear.

computer lance (cont’d)

A greedy man, that’s who. A man who isn’t satisfied with what

he’s got. A good job, a good home, a lovely fiancé.

lance

(eyebrows risen)

What’d you say?

computer lance

Well now, it appears I have struck a nerve. Your fiancé,

Chelsea.

lance

Leave her out of this, dammit!

computer lance

I didn’t bring her into this. You did.

Lance punches Computer Lance in the face, but his fist

phases through his head like nothing. Lance is taken aback by Computer Lance’s

transparent form.

computer lance (cont’d)

Because of your thievery, not only do you two not get to

marry, but she goes down with you. Your sins affect her. Your burdens lay on

her as they do on you. Your troubles are her troubles too.

lance

NO!!!

Lance runs through Computer Lance and goes to the elevator.

He presses the button, and the elevator opens. He sees that there is no

elevator, and he looks down and sees a long drop.

computer lance

Like I said, nowhere to go but down.

The doors on the side of the elevator move, which causes

Lance to lose both grips on the sides. Lance falls down the elevator shaft—slow

at first, but he falls faster and faster.

As he continues to fall, Lance sees a glowing light. The

light gets brighter and brighter to the point of blinding Lance.

cut to:

int. – lance’s office

We see Lance suddenly lift his head up from off his desk. As

it turns out, Lance has been asleep and was having a nightmare. He looks at his

computer and sees that the files have not been transferred yet.

His phone goes off. Lance picks it up and sees Cliff is

calling. He answers it.

cliff

Well, is it ready?

lance

No. No it is not.

cliff

Well, hurry up then.

lance

No. I’ve changed my mind. I’m happy with what I’ve got. I

don’t need you or your money. The deal is off.

cliff

(angry)

You son of a—

Lance hangs up. His phone goes off again. He sees Chelsea is

calling.

lance

Hey, babe.

chelsea

Lance, where are you? I’m at the venue. Are you okay?

lance

(reassured)

Yeah, I am. I’ll be down there in 15 minutes.

chelsea

Okay, then. I love you.

lance

I love you too.

Lance hangs up. He uses his mouse button to cancel the

download options. Lance smiles after canceling everything. He grabs his hat,

suitcase, and jacket and walks out of the office,

We look back at his computer and see something unexpected.

There is a window on his computer that says one file has been downloaded. We

then hear the sounds of Computer Lance’s evil laughter in the background.

the end