Blue Grey Red Memorial

by ASHLEY DAWSON | 3rd Place, student prose contest

written by Circumstance

EXT. FLOWER PRAIRIE - SUNNY AFTERNOON

Large, grey cinder blocks sit around an ashy fire pit.

The grey sits within the midst of color: chrysanthemums, carnations, azaleas, lilacs, daffodils, calla lilies, roses. It’s a communion planted among the fields of tall, dry grass.

A breathing, coloring and feeling world seeps out of the picturesque clearing. Still, the gray bricks sit there.

Beyond the noiseless scene is a dirt road. The road looks like it’s been well-traveled, but unused as of late. Weeds split the packed dirt and creep along its surface.

In the distance, a red pickup truck treks down the road. It stops at the end of the dirt and turns off. The tires are worn, and the paint is chipped. The driver’s door uncloses.

A skinny, washed-out man in his early 30s steps out. His thinning hair is a mosaic of brown and grey.

A little girl with unruly blonde hair climbs from the passenger seat to step out on the driver’s side. She stands with him in shorts, a t-shirt, and bright orange flip-flops.

She looks up at the man as he looks out at the clearing.

When he doesn’t move, she considers a flower from the road.

SIERRA

Daddy, what’s this flower called?

He looks at her, kneeling down and gently taking the yellow. He examines it comically closely, furrowing his eyebrows.

DAVID

That’s a weed.

SIERRA

It’s pretty for a weed.

DAVID

Well, there are loads of ‘em. Some are designed to be pretty.

She looks at the dirt and points.

SIERRA

That one’s like in the driveway.

DAVID

Yeah‚ yeah, it is. You’re so bright.

SIERRA

(shrugs)

It just looks like a spider with too many grass legs.

DAVID

Well‚ I guess so‚ It’s called crabgrass.

SIERRA

What’s this called?

DAVID

Oh, that one's a dandelion.

SIERRA

I like dandy-lions.

DAVID

I know, kiddo. Com’ere. Let me show you something.

He rubs the dandelion on her hand and up her arm, leaving a yellow trail of dandelion and utter betrayal. She cries out, yanking her hand away.

She tries to wipe the yellow off.

SIERRA

That wasn’t nice.

DAVID

All right, all right. (placating gesture) Here, I’ll help you wipe it off.

He licks his thumb and reaches for her arm. She screams.

DAVID

Hey, hey, I just want to help!

SIERRA

No! Gross! Get away! No!

He chases her around. Her shoes flip-flop. He scoops her up and swings her around. She’s laughing. He smiles at her. He sets her on her own two feet.

DAVID

There’s some water in the truck. You can use that to wipe it off.

SIERRA

Okay.

She runs around the truck, and her bright orange flip-flops clomp loudly against the dirt road.

She climbs up into the driver’s seat, grabbing a water bottle. She climbs out of the truck and pours the water on her arm. The water runs off her hand and begins to puddle on the dirt road. She scrubs the yellow on her arm.

He watches her, his expression unreadable.

Then, he heads over to the trunk bed, popping the tailgate. He hauls sandbags and paint cans over to the grass clearing. His daughter grabs his hand as they look down on the firepit.

Then, with the faraway look in his eyes, he gets to work.

He moves the cinder blocks away from the firepit. He dumps the sand into the hole, smothering the ashes within the pit. He lays the cinder blocks into a line.

One by one and heavy clink by heavy clink, each cinder block heaves up onto another one. All of the bricks are lined up.

They run across the sand covering the old firepit. A barrier. It’s a wall five cinder blocks high and three blocks wide. A canvas.

He pops the paint cans open with a screwdriver: yellows, bright blues, purples, magentas, whites, oranges, reds.

It's a colorful palette next to the dull, grey bricks.

Then, yellow slashes across the bricks. Purple dances along the edges. Magenta curves and twists. White forces itself in, smudging with the other colors. Red carefully aligns itself. As the sun begins to set and his daughter sleeps in the passenger seat, light blue takes its place among the colors.

He steps back and stares.

He stands between his truck and the color wall.

He looks back over his shoulder as he leaves.

The sunlight shines from beyond the red pickup, casting his shadow along the sand and onto the bottom of the color wall.

He packs sandbags and paint cans back into the trunk bed. There's still sand inside the bags. The paint runs down the sides of the cans.

He shuts the tailgate.

EXT. FLOWER PRAIRIE - NIGHT

He opens the tailgate. It's empty save for a white paint can. He takes it out, making his way over to the color wall.

The beginning of the sunrise disrupts the sky: light, blurred, dark. Most colors in the clearing are quiet, with the hues of blue humming a little louder in the low light.

He crosses the distance from the red truck to the wall.

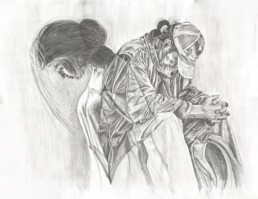

An anorexic figure stands at the bricks with a dark blue can of paint. Their pale skin stands out in the darkness.

They're in a black garment similar to a child's feather play dress. They have a bridal hat with a dangling curtain of beads covering their mouth. They are barefoot.

He sets his paint can down.

DAVID

I hope you aren’t planning on painting this with that color.

The figure kneels to the can and tries to open it. They're having trouble as if they can't open it themselves.

DAVID

I’m serious.

No response. He kneels down, snatching the screwdriver from their hand.

DAVID

You're not from around here, are you? You aren't allowed to paint this. It's a memorial for—

BRINLEY

(raspy)

Painters derailed by circumstance.

The figure sifts the sand between her fingers. Crazy woman. He rubs his temples and sighs, sitting back on his haunches.

DAVID

Okay‚ lady, do you have anyone I can call to pick you up?

BRINLEY

You left.

DAVID

What are you—

The figure scoops and flings sand into his face and mouth. He loses balance and falls, grunting when he lands on his back. The figure grabs the screwdriver, returning to her frantic attempts at opening the paint can: no closer to her goal.

He wipes at his face and spits out the sand. He sighs, pushing himself up. He grabs the screwdriver from her.

The figure grabs the bridal hat and flings it off dramatically. His eyes go wide.

BRINLEY

I’m not done.

DAVID

What are you on about, Brinley?! I thought you were—the whole town thought you were dead!

BRINLEY sits back with the screwdriver, staring impassively. Her blue eyes are bloodshot, and she exudes exhaustion.

His expression swims with relief, sorrow, and anger.

DAVID

Why?!

BRINLEY

You wouldn't understand.

DAVID

I wouldn't—?! (calms himself, still tense) I understood back then. Back with your parents. When you said they didn't understand. Remember that?

BRINLEY

You wouldn't understand now, David. Painters are rarely understood.

DAVID

Maybe because these painters leave their families and their town to—to pursue careers in vandalism!

Brinley doesn't glance at the wall, not even when DAVID gestures frantically at it.

DAVID

You didn't even give me a chance to understand. You just left again!

BRINLEY

I'm sorry.

DAVID

No, you aren't. You do this every couple years. You can't keep doing this to me…to her.

BRINLEY

Passion isn't easily understood.

DAVID

It's not passion! It's crazy! You left her at the house: alone and hungry while I was at work!

BRINLEY

You left.

DAVID

I was at work.

Brinley doesn't move, twitchy and pale. David stares and his expression slowly morphs into one of misery. The 'rise lights more of the sky than it doesn't.

DAVID

I can’t do everything.

BRINLEY

...

It's like talking to a wall.

DAVID

You don't understand. I work hard to take care of his kid.

BRINLEY

...

A grey concrete wall.

DAVID

You can't just let us be, can you? You just always have to come back and stir trouble.

BRINLEY

I wanted to see you.

The sun begins to cast the brick wall's shadow onto Brinley's stature. David looks up at the colorful painted wall, clenching his fists in the sand.

DAVID

No, you just want to screw everyone over. Why can't we just have this? If you won't come back for us, why can't we have this?

Brinley stares, eyes focused on him as she itches where her throat meets the feather dress. She obviously doesn’t care.

David moves slowly, distraught.

He takes the screwdriver from her and pops the can open.

Brinley watches, gaze fixed on the wall behind him.

As David steps back, the wall's colors become decipherable.

It's a beautifully painted face: Brinley's face.

Slashing yellows, dancing purples, twisting magenta, smudging white, aligning red. It's an awe-inspiring, steadfast feeling of passion amidst the grey brick wall.

David walks back to the white paint can he came there with.

Brinley stands with the blue bucket in hand, watching him.

BRINLEY

Aren’t you going to stop me?

DAVID

Not anymore. Have at it.

Brinley heaves the bucket. Dark blue paint splatters against the memorial's intricate details.

The sunrise shines from beyond the brick wall, casting its shadow over them.

Birds chirp as they fly overhead. The flowers flutter in the breeze.

David turns and walks out of the shadow to his truck.

Brinley stands there and stares at the wall.

The red truck departs from the clearing.

The blue paint drips down the bricks.

Still, the grey bricks sit there.

Ω

Ashley Dawson is a daughter, an aspiring writer, and a student at Tulsa Community College.

From Beverly Marshall: Every day we pass strangers. We see family & friends. We see faces. We see emotions. We see the Human Experience. Every face tells a story. Every emotion grips our hearts, and sings, or screams to our souls. Those faces, those emotions, every story told deep in their eyes. We all have those feelings. The ones that can come out of nowhere and bring such joy... or such pain. What power the emotional soul has….

Don’t Fall, Sister

by DANA ROBBINS

Like so many things, it was fun in the beginning,

riding the subway to my first summer job, in midtown,

learning how to match my legs to the rolling of the train

as if I were on a ship, how to hold the pole just right,

not too high, not too low.

After the stroke, riding the subway was not easy,

but I had to get from Brooklyn to my job in Manhattan,

and every New Yorker knows the bus is too slow.

Not easy, letting two trains go by before I could squeeze

in. Once I got caught in the door, which closed faster

than I could move.

Yet there was a joy to it, being part of the great

moving mass: a mother from Latin America with long

braids, next to an African woman brilliant as a bird

in a colorful headdress, cheek by jowl with a young

Hasidic woman with a double stroller and tired eyes,

drag queen sitting next to a clean-cut Midwesterner.

And the music, don’t forget the music, hollow pipes,

played by diminutive Peruvian men, saxophone solos;

break-dancers who somersaulted through the moving

train; the barbershop quartet that, as I lurched trying

to hand them a dollar, sang “Don’t fall, sister, don’t fall.”

Ω

After a long career as a lawyer, Dana Robbins obtained an MFA from the Stonecoast Writers Program of the University of Southern Maine. Her work received first prize in the Musehouse Poem of Hope Contest and third prize in the Anna Davidson Rosenberg Award for Jewish Poetry in 2018.

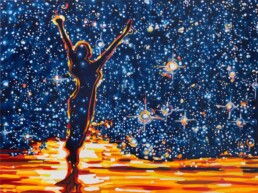

Annika Connor is an artist, SAG-AFTRA actor, and screenwriter. She studied Painting and Performance at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Connor uses strong symbolism, passionate imagery, and/or humor to ignite the imagination, and employs precision, detail, and allegory to show art that's narrative and mysterious.

Planting

by ALLISON PLOURDE

Katherine started to wonder about her husband when he bought a new shovel. It was an expensive shovel, one with a sharp edge on the blade and a metal handle. She noticed it leaning up against the drywall in the garage, unused with the price sticker still on the shaft. After taking out the garbage she came inside and approached her husband sitting in his armchair, flipping through baseball games on the TV.

“Honey, when did you get that shovel?” Katherine asked. It came out as an accusation.

Rick looked over his shoulder at her briefly before turning back to the TV guide. “Just yesterday. Your mom asked me if I could come by and plant some flowers for her.”

“Don’t they have a shovel?”

Rick snorted. “Your dad hasn’t done a lick of yard work in his life. We didn’t have one either, babe.”

Katherine shrugged. “You’ve got a point.” She leaned over and took the empty beer bottle out of his hand, grabbing him a new one from the fridge. They had their little clockwork moments like that, two trapeze artists meeting perfectly midair. It told Katherine that they were still working. Most of her friends had been divorced by now, so she was always looking for signs that she and Rick must have been different. He planted a kiss on her cheek at the handoff of the bottle, the scent of hops carried on his warm breath.

After pouring herself a glass of wine, Katherine walked out onto the porch to sit in her wicker chair and listen to the breeze. With the sun setting behind the house, she could watch the shadows from the roof and trees stretch down the driveway and across the street. It was the most typical suburban neighborhood she could imagine, and it sometimes gave her a stomachache.

Katherine heard the garage door open and watched her daughter ride her pink push scooter down the slanted driveway, coming back in a loop on the sidewalk. Her body clenched with the sort of fear that only gripped her since she became a parent.

“Annie, be careful!” she called.

“Daddy said I didn’t need to wear my helmet!” she responded, giggles bubbling out between her tiny teeth.

Katherine sighed and rose out of her seat. “Well, Mommy says you have to!” She spent the next several minutes chasing Annie around on her scooter until she inevitably tipped over into the grass and burst into hysterics.

While she tended to her daughter’s skinned knee, Katherine looked into the open garage. Rick stood with his arms crossed over his chest, having surveyed the series of events. “Rick, seriously?” she chided.

Unmoved, Rick said, “Well, she didn’t hit her head, did she?” As Katherine opened her mouth to respond, her husband turned mechanically on the ball of his foot and went inside.

Rick held the reins much looser than Katherine—showing Annie PG-13 movies, allowing her to walk a few blocks on her own to meet up with friends, and sometimes forgetting to read the labels on granola bars for trace amounts of her few mild allergies. Usually, though, he wasn’t so callous. One minute, he was volunteering to landscape for his in-laws, and the next he was turning his back on his crying daughter. Katherine felt the same disgust toward him that she imagined her divorced friends used to feel, and she swallowed it down. Annie was back on her scooter with a bandage and helmet shortly.

The next day, Rick came home from work in new hiking boots. He and Katherine had gone hiking on their honeymoon in Jackson Hole nine years ago, but he hadn’t expressed much interest in the outdoors since then.

“Those are pretty fancy, hon,” Katherine said from the couch, her tone bristly by accident. She was holding knitting needles like drumsticks and a bundle of dark green yarn in her lap. A long, knitted rectangle draped over her legs onto the floor. She took up knitting a few months ago when she decided she needed a hobby. Using her hands for something so meticulous sent her brain to worry about her extremities. She only picked it up for a few minutes at a time, every few days, and she hadn’t finished her first project yet: a blanket. At first, she found herself having to redo a row here and there, but by now she just couldn’t figure out how long the blanket should be. She was constantly undoing the yarn, pulling it apart, and then knitting the same rows again when she changed her mind.

Rick propped one foot up on the heel and waved the boot around. “Oh, these? I thought I should have something for when it gets colder out. My socks always end up getting wet through my other shoes.”

Katherine nodded to his explanation, despite it being early August.

He added, “It’ll help me at your parents’ house, too. You know, when I’m helping with the yard.”

Later, parked in her wicker chair after dinner, she considered her husband’s two latest purchases. He was the least handy guy she knew, and didn’t talk to her parents enough for them to ask him for a favor like that. She peeked into the garage to see if the shovel had been used yet; it hadn’t. Rick had left the new hiking boots beside it against the wall, perfectly parallel like a prison lineup.

The day after that, he showed up with a new garden hose. Katherine was sitting on the porch when he pulled in, and she met him in the garage as he hefted the box out of his trunk.

“You starting a landscaping business?” she asked as a greeting.

Rick laughed but only briefly, perhaps reacting to the tightness in her voice. “Your parents haven’t touched their yard in years. No shovel, and their hose is full of holes. Now, this one…” He pointed to the yellow graphic on the box. “…this one is ‘indestructible.’” He dropped the box down beside the shovel and the boots, a tiny cloud of dust and dirt puffing off the concrete floor. Brushing off his hands, he walked around Katherine and into the house.

She paced back and forth near the small collection of gardening tools, chewing on her thumb nail. The idea of Rick having a life outside of this one, a life that involved gardening for his mother-in-law, bothered her. They didn’t do secrets. That’s why they were still married, Katherine thought, because they had their work and their knitting and their Annie and everything out on the table. And why would he keep this, of all things, a secret?

The homicidal nature of the objects, together in a line against the wall, was not lost on Katherine.

The next night, Rick said he was having drinks with some coworkers. This wasn’t unlike him; she would portion out his dinner and cover it with cling wrap, making sure to keep the sides separate on the plate from the entree. He would get home after she put Annie to bed and he would usually be horny, engaging Katherine in quick, sloppy sex before rolling over snoring without setting an alarm for the morning.

When she got the text from Rick that he would be out late, she felt the skin on her face tighten and her mouth press into a thin line.

Annie, who was setting the table for the three of them, asked, “Mommy, what’s wrong?”

Katherine straightened up and smiled. “Nothing, baby. Daddy just won’t be home for dinner tonight.”

Annie frowned and turned around, returning to the table and picking up one of the place settings. “Will he be back to tuck me in?” she asked, although Katherine knew she was smart enough to probably know the answer.

“We’ll just have to see.” Katherine kissed her daughter on the top of the head. “Go work on your homework while I finish up dinner, okay?” Annie reluctantly left for the living room where her math workbook sat open on the couch.

When she was sure Annie was occupied with her work, Katherine stepped out of the kitchen to the garage. She peeked outside the door and scanned the walls. The shovel, boots, and hose were gone.

That night she stayed up watching TV instead of going to bed before Rick got home. She hadn’t been able to eat at dinner, and the movements of each joint in her hand sent electric currents down her fingers as she compulsively ran them over the TV remote’s buttons. Her gaze sat unfocused ahead of her while her mind raced, overly aware of the breath whistling in and out of her nose. She ran through the conversation she meant to have about the shovel, over and over. Where and why and what could he possibly be digging for at the bar? What would he need with a hose this late? But then she heard the garage door open, and Katherine snapped to attention, mentally scolding herself for worrying so much about gardening tools.

Rick came into the house without his shoes on but obviously sober. “What are you doing up?” he asked, flipping a light on as he entered the kitchen to look through the fridge.

“Just feeling antsy tonight, I guess.” Katherine turned the TV off and rose from her chair. “How were drinks?”

Rick shrugged without making eye contact. “Boring. Reggie and Paul couldn’t come out tonight so it was just Hank and Walter.”

Katherine nodded, not attempting to put names to faces.

Rick looked at her briefly before pulling his perfectly made plate out of the fridge. “Something wrong?”

Katherine realized she was standing in the middle of the kitchen, staring, wringing her hands. “Oh, no, sorry. Probably just overly tired, that’s all.”

Rick looked at her again, longer this time. “All right. Why don’t you go up to bed, and I’ll meet you after I eat?”

She nodded and smiled. “I’m just going to grab a bottle of water out of the garage.” She hurried out of the kitchen and toward the garage door before he could respond.

Katherine peered her head out the door before stepping onto the concrete floor barefoot. The shovel was returned against the wall, and beside it were the new hiking boots, replaced in just the same configuration as if they hadn’t moved. The garden hose was out of the box, resting in a pile of loose coils and twists beside the other items. She approached to get a better look: the shovel had some dirt on the blade that looked to have been mostly scraped off. It wasn’t shiny anymore and the price sticker was crudely picked off by hand, small bits of white residue and adhesive remaining. The boots were caked on all sides with mud. The ends of the laces were dark from being stepped on and dragged along the ground. The shiny green of the hose had dulled in a few places as if it had been sitting in someone’s yard for years. Half-formed, drying footprints led from the garage door to where the shoes rested beside the shovel against the wall. Both the shovel’s blade and the tops of the brown boots were speckled with small, dark spots. Even the hose had a few small rust-colored streaks along its length. Faint aromas of disinfectant and metal permeated the garage.

The floor waved and ebbed in Katherine’s vision; she leaned against the wall briefly as the nausea passed. She nearly forgot to grab a bottle of water out of the fridge on her way in. When she opened the door, she almost collided with Rick’s broad chest.

“You alright? You look like you’ve seen a ghost.”

Katherine swallowed and nodded. “Really, do I?” she sputtered, touching her cool cheeks and trying to smile. “Like I said, I must just be antsy.”

Rick narrowed his eyes but nodded, angling his body for Katherine to get inside. She felt her pulse rise into her throat and beat in her ears as she climbed the stairs, crunching the plastic of the water bottle between tense fingers. Taking a moment to collect herself in the dark hallway, she gently knocked on Annie’s bedroom door and entered.

“Hey, baby,” she said, lowering onto the white comforter.

Annie pulled her covers up to her chin and smiled. “Mommy, is Daddy home?”

“Yeah, he is, but he’s tired I think.” Annie’s little shoulders fell under the blanket. Katherine petted her hair. “I’m sorry. I think we need to give Daddy a little alone time tonight.” Her breaths were thin and whistled out from her nostrils shakily. Feeling herself straighten, she added, “But I have an idea. You’re getting older, after all.”

Annie sat up against her pink pillow. “What do you mean?”

“I think it’s about time you have a little more…privacy.” Katherine stood up from the bed and motioned for Annie to follow her to the door. Approaching the doorknob, she pointed to the raised circle at the center. “This is how you lock your door. If you press that button, you become the only person that can open it.”

Annie took the doorknob in her hand herself. “Daddy said I’m not allowed to lock my door, in case of an emergency.”

Wringing her hands, Katherine said, “Well, think of it this way. What if there’s an emergency somewhere else in the house? What if someone bad gets inside, and you need to be safe?” Annie’s eyes widened, and Katherine bent down beside her, touching her cheek. “Oh, baby, I don’t mean to scare you. This is for…just in case, alright?”

Annie nodded, still holding the doorknob.

“Here, I’ll go out in the hall and you try it,” Katherine said, quickly squeezing Annie against her chest in a tight hug and then walking into the hallway. After she closed the door behind her, she pressed her hands against the wood and spoke to Annie. “Okay, press the button.”

Annie pressed the lock and the metal made a dull click. Katherine’s spine loosened with a sigh. “Good girl. Now, just in case, how about you keep it locked tonight? And then I’ll knock in the morning. It’s just a test. Just to try it out and see if you like it. For privacy, and safety.” Her forehead was now pressed against the door, and she felt her warm breath tickle the tip of her nose as it bounced back at her. She knew she was scaring Annie, and her words betrayed her own fear, but she needed her daughter safe.

“Okay, I’ll keep it locked,” Annie answered through the door. “Goodnight, Mommy. I love you.”

Katherine let a small smile cross her face for the first time all day. “I love you too, baby.” She finally pushed away from her daughter’s bedroom door and turned to face the rest of the house. At the end of the hall were the open double doors to the master bedroom, the TV glowing from within. Katherine stood in place, breathing rhythmically with the soft flashes from the screen. After pushing her doubts deep within her gut, she walked down the hall and entered the bedroom, where her husband was not asleep.

Ω

Allison Plourde is an NYC-based prose writer from the suburbs of Chicago. She holds an MFA from Stony Brook Southampton. Her work can be found in Bending Genres and Broadside Literary Arts Journal.

Diana Branzan is an illustrator and designer based in New York, NY.

A Finger Painter Derailed by Circumstance

by ERIC LAWSON

I used to smear paint on these same walls

for hours, oblivious, and perfectly content.

Primary colors swirled together quaintly.

Life imitating art imitating life, replicated.

But somewhere along the way I started

worrying about my posture and a 401k.

And utilities and sodium and calories.

And new school clothes for the munchkin.

And rent and car payments and exercise.

Yet at night I dream about feeling the wet

textured slime oozing between my fingers.

Creating a valley full of elk and squirrels.

Or lily pads with frogs and ducks in a pond.

A hellish forest fire blaze belching smoke

skyward along the pale coastal highway.

Infinite fractals spring forth from ancient

man-made mythological and dark desires.

The quest for more light is endless.

How many stars must I chase only to

ignore the closest sunlight on my face?

How many solid relationships must I flee

from because the idea of commitment is

too stifling, too vanilla, and too final?

How many screens must I view daily in

order to quell my boredom and curiosity?

I need to unleash something feral.

I need a tangible tool in my hands.

I need to entwine and breed with chaos.

Verily, I vow to continue to map the

constellations by torchlight while

smearing finger paint

on my cave walls.

Ω

Eric Lawson is the author of the short story collection Circus Head (Sybaritic Press) and the forthcoming poetry collection Backseat Emperor (2nd Avenue Press), in which this poem will appear. He co-wrote the screenplay for the horror anthology film Body Count ("Holly Hatchet" segment). He is also the host of the video podcast Make Your Own Fun on YouTube.

Jasper Glen is a poet and collage artist from Vancouver. He holds a BA in Philosophy and a JD. His poems appear in A Gathering of the Tribes, Amsterdam Quarterly, BlazeVOX, Posit, Rogue Agent, and elsewhere. His collages are forthcoming in BarBar, Liminal Spaces, and Streetlit.

Where Crown Crosses Ocean

by GIANFRANCO LENTINI

"The Sun woke me this morning loud

and clear, saying 'Hey! I've been

trying to wake you up for fifteen

minutes. Don't be so rude…'"

—Frank O’Hara

CHARACTERS:

READER—an everyman, hasn’t slept all night.

FRANK O’HARA—a ghost of a poet, gone too soon.

SETTING:

The beach on Fire Island Pines, Fire Island, New York.

Just off of where the boardwalks of Crown Walk and Ocean Walk intersect.

TIME:

Summer at dawn.

The sun has begun to peek over the Atlantic Ocean, bathing the beach in a pale pink glow, growing more vibrant and orange by the minute.

Sitting on the beach, feet in the sand, are a READER and FRANK O’HARA. They sit peacefully. FRANK faces the tide. The READER slowly pages through yesterday’s edition of The New York Times.

The READER eventually surfaces from the page.

READER

They’re calling you “a catalytic figure.”

FRANK O’HARA

Are they?

READER

Who had “hundreds of friends and lovers throughout his life.”

FRANK

Such are the poetics of hyperbole.

He smiles to himself. The READER puts down the newspaper. The waves continue to lap the shore. The men watch.

READER

Did you know?

FRANK

Know?

READER

That you’d be remembered this way, when you stepped out?

FRANK

In front of the—?

The sunrise’s glow is briefly distorted by the sound of breaking tires and a flash of headlights, but then all returns to normal. The READER’s silence affirms FRANK’s question.

FRANK

Every artist hopes to be remembered.

Pause.

FRANK

But let’s leave the catalytic nature of romanticizing tragedy to the page. Hm?

Pause.

FRANK

Instead, I would like a Coke.

READER

(impatient, reciting from memory)

“Now I am quietly waiting for the catastrophe of my personality to seem beautiful again, and interesting, and modern.”

FRANK doesn’t react. Instead, he continues watching the tide.

The READER grows discontent.

READER

Are you not the man who wrote that into existence? Are you not Frank O’Hara?

FRANK

I am.

READER

Well?

FRANK

Well, it feels as if you may be searching within my work—and within the momentary spotlight of my remembrance—for an intention, perhaps even a prophecy, to my…to my departure…and I don’t think that’s wise.

READER

But were you not already hurting when it happened?

FRANK

Of course. Of course I was. I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t hurting. Emotionally or otherwise. How else would I have been inspired to feel? To write? To create?

READER

So you had no plan—no intention—of putting yourself in front of that jeep that night?

FRANK lets his mind roll over with the tide.

FRANK

(Reciting)

“You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.”

READER

You didn’t say that. That was—

FRANK

James Baldwin. I’m aware. 1963.

READER

So, then?

FRANK

So, then, you—you percussive, well-versed reader—should also know you are more than your pain. You are smarter than your pain. You are, in fact, not your pain.

READER

But we’re talking about you.

FRANK

Are we?

The READER grows uncomfortable.

FRANK

You understand how universal it is to hurt, to weather emotion, to be alive. And you are wiser than the deceptive thoughts telling you how impractical it may feel to remain alive.

READER

You don’t know me.

FRANK

No, but I know ideations when I hear them.

FRANK finally looks the READER deep in his eyes.

FRANK

Do not allow your theories—of what I did or did not do or say or write—to justify the act that you’ve been silently considering…all because you believe I took the easy route.

The READER is stunned, unable to look at FRANK.

FRANK

You don’t need misfortune in life to be remembered in death. What you need is solely the fortune to live. And for that to be enough.

READER

But sometimes…

FRANK

Go on.

The READER tries to hide tears.

READER

It’s all just unbearable. This obligation to be…present…human…here…alive.

The READER looks about as if a solution—or escape—to his pain might lie around them. He stares helplessly down the endless stretch of beach. Nothing.

READER

I’m tired. All the time. And for what? For what it’s worth, I don’t know.

FRANK

(gently, reciting)

“If you don't appear at all one day they think you're lazy or dead. Just keep right on, I like it.”

READER

You said that.

FRANK

(smiling)

I did.

The READER thinks for a moment…and then looks curiously at FRANK.

READER

Do you think I would have known any of your words had you not—

FRANK

Died before my time? Truly, I have been wondering that myself.

FRANK laughs, which comforts the READER. They then eventually come to a peaceful silence together.

FRANK

One day you’ll know what it’s worth, both the pain and the pleasure. But your day of knowing is not today. Find comfort in that. And allow that to allow you to be here.

FRANK stands up. The READER looks up at him.

FRANK

Sunrise. I have to go.

READER

But we just met.

FRANK

Perhaps. But now you need some sleep. You deserve it. Oh, and don’t forget that.

FRANK points, and the READER turns to grab the newspaper off the sand.

When he turns back, FRANK is gone.

The READER looks back at the water. He sits for a moment longer. Then he folds the newspaper, stands up, brushes off the sand, and returns to the boardwalk.

We listen to the tide for a moment longer.

Ω

Gianfranco Lentini (he/him) is a NYC-based queer playwright, teacher, and First Generation Italian American. His work has been developed and produced from North Carolina to Toronto, as well as published by Apricity Magazine, The Coachella Review, Mini Plays Review, and Molecule Literary Magazine. He is currently an Adjunct Professor at NYU Tisch, a Wendy Wasserstein Project Representative for TDF, and a proud Member of the Dramatists Guild of America. You can learn more at heygianfranco.com.

One More Bearer in the Puritan Parade

by BENJAMIN CLABAULT

I. The Mass Bay Colony: a Quarry

Her Puritan hand stiffens

beneath the Biblical spine.

I know that cramp:

the hammy flesh

in which my phone’s congealed.

Her Book gives life

because it’s dead,

each word a pebble uneroded,

as jagged in the new England

as in the one she once called home.

But I scorn her dead paper—

no borrowed truth for me!

I can google for ceramic tiles

and build a path towards superation.

And when that’s insufficient,

when I’m hungover or heartbroken, and

hungry for denser stone, some pixelated volume

from the Borgesian Library of Babel appears,

because God or Gates or the algorithm’s great

and angels understand the divine mandates

of search engine optimization.

It’s absurd and I hate it.

I sit on that porcelain contraption,

the most important invention here,

and let the “device” dissolve between my fingers,

meld to the bathroom floor.

Flush. Wash.

I leave the screen and walk through woods

on a path of blue, sharp stones

lain before me by a stern volunteer

revising a secret smile.

Back home I write. My script’s

softer than her Bible type, but

harder than her molten hand.

II. Puritan-Damp

Living without faith is like

having your arms stuck in Puritan stocks

bolted to the ocean floor.

The heart splinters and

plummets to the toes—like

styrofoam cups they shrivel.

My mind’s more architect than

visionary, more cement-mixer

than primordial stew.

You can make sweet paste

from butterfly wings

and sell it in a tube—

but to call providence

comely is calumny—to complete

a thought’s to square a hole,

and to write—that buzzing

is all and nothing—is

to wet dry paper. Fool.

III. Puritan Poet Erotica

She peers into her house through flaming lips

and envisions penetration with pen.

My world too burns—in Lewiston, Alberta, and

a thousand enflamed entrails.

Both our shelves have Bibles—her’s oft-read,

mine half-imagined. Surely scriptural curls

align to form her tendons—and her poems

contain only Biblical prescriptions?

But no—her house-burning tale

has Bible-like covers, but the actual poem,

the fleshy bit in the middle,

dissolves in intelligized womb.

Ten-timed mother with throbbing heart

imprinted on virginal screed, she passes

the charred vestige of her Puritan hut and

thinks: I lay there. And he lay with me.

Fuck stereotypes. Puritans loved sex—

may the pleasure of the marriage bed produceth

the greatest of joys. Anne wasn’t known in town

as the poet, but as the bedful screamer.

I wonder what sort of breasts she had—

if living before internet porn

and globalization, she knew how many

types of nipples are out there?

I wonder about her kinks. Would I

have been too boring for Puritan-Anne?

Could a guy raised on Hollyweed sex

dance to Solomon’s songs?

I imagine us in that house together—or no,

after, lying entwined on those blackened remains,

my tongue traveling like a futuristic ice cube

from her neck to her breasts with their singular nipples and

down, down, down to the brine of the pearly gates,

and here I bare it—white-inked, half-flaccid, unsure—and

thrust it toward biblical abode,

and as I move I say, “I don’t know, I don’t know, I don’t know”

and she assures, “Me neither, me neither—

but just keep going.”

Ω

Benjamin Clabault is a writer and teacher from Cape Cod, Massachusetts. He lives with his wife in Morgantown, West Virginia, where he’s pursuing a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. His work has been published in Literary Traveler, The Bookends Review, and Inlandia: A Literary Journey.

Katherine Madden teaches Photography and Digital Art at Jesuit High School in Sacramento, California. She holds a PhD and MA in Critical Studies from the University of Southern California and a BA in Film and Media Studies from UC Irvine. The best part of her day is spending time with her husband, sons, and dachshund, Rosco.

The Monster and the Boy

by JAIME GILL

Today, the monster steps into the world. Today, unhooded, he is seen.

He has done this for many years now, ever since he began to understand the possibilities Halloween offers him. For one night, the town is transformed, becomes a wonderland of the ghoulish and grotesque. A town made for him.

When he was very young—before he became a monster—costumes were half-hearted, more comical than frightening. A girl might perch a witch’s hat on blonde curls and clutch a broomstick for trick-or-treating. A boy might slick his hair back and wear ill-fitting plastic fangs. Now people go much further and this strange fascination for the macabre has spread, fungus-like. It isn’t just kids who dress up anymore. Now teenagers, students, twentysomethings and office workers spill out onto the streets costumed, making their way to parties or bars freshly festooned with spiderwebs and lurid splashes of fake blood.

On past Halloweens, the monster has watched ghastly-visaged zombies, flesh grey and peeling, squawking on phones. He’s seen Frankenstinian creations painted into a state of rot, a pallor right down to their cigarette-clutching fingertips.

The celebrity costumes don’t interest him, and often bewilder him. It’s the monsters he appreciates. They provide camouflage as he goes out, hunting for something he dare not name, even to himself.

The boy’s parents disapprove of Halloween. His father says it’s a money-making scam ripping off parents. His mother says horror shouldn’t be glamourized, that children see too much too young: “violence…and the other stuff.” Both agree the boy is too young to trick-or-treat at seven, though his twin cousins—a whole year younger—do it with their parents. His cousins told him it was amazing, that everyone looks scary but it’s fun being frightened, and you come home with pockets full of treats.

The boy lives in a town without magic. There is only school, home, and two after-school sports clubs a week. Every week. He knows there’s no Santa Claus or tooth fairy, since his parents don’t believe in superstitious nonsense. He knows there’s probably no such thing as monsters, but even the idea of people pretending thrills him. Pretending is a kind of magic, too.

It maddens him to think of that thrilling, frightening world happening tonight on the other side of these dull brick walls.

Late afternoon and the streets slowly fill with aliens, ghouls, werewolves, ghosts, vampires, and grotesques. Still, people still stare at the monster as he walks. Most try to do it discreetly, sideways glances followed by whispers and giggles, but others brazenly turn as he lurches past them. One young woman costumed to look like she’s been electrocuted shouts “incredible make up.” Some take photographs.

The monster ignores these minor attentions. On any other day it would be worse, he knows. They would flinch from him. Their mouths would gape. If he ran at them, they’d flee shrieking. Only today can he move freely through their world and be treated as if he were normal.

To be outside and hoodless is extraordinary. He can hear chatter and unmuffled street noise, see the whole panoply of the town through his unobscured peripheral vision. So many people. So much life. How he hungers. How he wants.

The boy plans his escape carefully.

Every day, his mother collects him from school at 3:30 p.m., and he is allowed supervised television until his father gets home at six. They eat between seven and eight, and then the boy does homework in his room or reads books while his parents watch television downstairs. That hour is his chance. He’ll slip out of the back door, through the garden, down the alleyway, and out onto the streets for his first Halloween.

It's 4:30 p.m. now and the boy watches “She-Ra.” His mother likes it because she used to watch an old version when she was a girl. She sits with him but doesn’t actually watch. She hunches over her laptop sending millions of messages, sometimes laughing or sighing at something she’s read. It’s annoying, but tonight the boy doesn’t care. He isn’t watching either. He’s imagining and anticipating. Tonight, the boy will seek monsters.

The monster climbs the hill slowly, passing gawping couples and gaggles of teenagers. Up here, a cold breeze blows in from the hills and kisses his face. So beautiful to be under the sky, unshielded and unhidden.

He finds an empty space and looks over the town’s haphazard, blocky sprawl. It rained earlier but the clouds are parting now so he can see the sun descending over the hills. Incredible to think that it’s one vast ball of fire—his enemy.

His enemy is beautiful.

Even through the cold air he feels its heat on his face. There will be pain later, but for now his heart is full. There are clouds on the horizon and they begin splashing red and purple, like the sky is a window being smeared by a clawing, bleeding hand.

The boy creeps down the stairs. Every creak terrifies. He doesn’t think he’s ever defied his parents like this before. Maybe in those squidgy lost years when he was still learning to speak and make memories.

He tiptoes through the kitchen, turns the key and steps out into chilly night. Everything’s more frightening than he’d imagined, the shadows in the garden bigger than they should be. Has he ever been alone, outside, in the dark before? No. But he won’t go back.

There are lights in the alley, but they’re far apart and weak, pools of meager light besieged by darkness. The boy looks to where the alley connects to the main road. There is more light there and faint sounds of laughter. The boy creeps to the road and skulks in shadows at its edge. He wants to see monsters but would prefer them not to see him.

Seven people pass, not one frightening. Just boring ordinary people in boring ordinary clothes. His heart leaps when he sees a dark, ragged shape. A vampire, perhaps, though he has a confused idea of what a vampire is, based on scraps of overheard information and children’s cartoons.

The vampire gets closer and the boy’s heart sinks. He knows the man beneath that splotchy makeup. That guy from the supermarket, the one with the big tattoo poking up from his chest into his neck. The boy can see the tattoo now. The man looks stupid and deeply unmagical—the boy has seen him selling dog food.

He lingers long enough for his fingers to shake and feet ache from the cold. Soon his father will go to his room to check on him. He dare not stay longer.

He’s walking back down the alley, legs heavy with disappointment, when he sees the shape coming from the other end, backlit. It moves strangely, too slowly. As if weighed down or dragging something. (A dead child, a dead child.)

Two images crush in on him, making it hard to breathe. The first is the shape, its hands lunging for his throat. The second is his father, angry and shouting.

He watches the shape’s slow, pained gait. It doesn’t look like pretend. The boy doesn’t want to see a monster anymore.

As panic surges, he counts the lights between himself and his garden gate, and then between the gate and the shape. He can get home before it can get to him, he’s a good runner.

The shape freezes at the sound of his racing feet. It doesn’t run, to the boy’s sharp relief.

He’s almost at his gate when his front foot hits a puddle and he skids. He falls and lands face forward, hard enough to smash the air out of his lungs. His hands hurt where they grabbed stone to break his fall. He looks up and the shape is lumbering towards him, vast against the streetlights. He tries to scramble to his feet but too late, the monster is here and it’s making a terrible noise but the boy is only dimly aware of that, because all he can see is its face, its face.

The monster has no face. No, not true, there is a face, but it’s wrong, like someone stabbed holes into an old, melted candle. There’s one tiny eye, silver and blind, and one huge eye reflecting the streetlights. There’s a rip that moves, and that’s the mouth.

The boy screams for his mother and the monster’s hands jerk towards him. The boy scrambles, finds a foothold and pushes himself off it, but then his skull bangs and everything goes wobbly black.

The monster looks down at the boy, then stoops. It’s dark, so the monster isn’t sure if that’s mud on the boy’s face or blood. He gently touches the face with a finger, then lifts it towards the streetlight. The red tinge terrifies him.

He should run. He did nothing wrong; he knows that. He was only taking a shortcut home through the back alleys he roamed during his own boyhood.

Then that boy had run and fallen. He’d tried to help, but the boy screamed. He’d only wanted to reassure him he meant no harm, but then the boy had run into that wall.

It didn’t matter that he’d done nothing wrong. If anyone found him with a bleeding child, alone in an alleyway…there would be no explanation that would be enough, even if he could get the right words out of his mouth, even if someone understood them.

Run.

But there’s a boy here, lying unconscious and bleeding. He might be badly hurt, might be in danger.

The monster was a boy in danger once. Fire climbed every wall. Nobody came to help until it was almost too late.

He lifts the boy, pain shooting through his scarred arms, and carries him to the nearest streetlight. He props him up carefully and digs a bottle of water out of his satchel. He pours it over the boy’s face to see how bad the cut is.

The boy spasms and opens confused eyes which widen with instant terror.

The monster’s own fear screams inside him. He knows his voice—that sibilant slur—will only frighten the boy more. And so he pours all his gentleness, all his human soul, into his good eye, trying to radiate the truth.

Magic happens.

In the thin streetlight the boy’s eyes recognize, understand, and soften.

“You’re helping me,” he says, wonder in his voice.

The monster doesn’t dare answer. In his heart emotions fight. The beauty of being seen, the fear of being caught, relief that the boy is okay.

“You’re not a real monster.”

“Yes I am.” How the monster hates the mushy hiss of his own voice.

“No, I don’t think so. You’re not.”

Why does the monster say what he says next? “This isn’t a mask.”

“I know.” The boy reaches up hesitantly, touches the monster’s cheek, and smiles as if he just discovered something surprising and wonderful.

It hurts to talk so the monster never wastes words. “Are you okay? Where’s your home?”

The boy hauls himself slowly but steadily to his feet and points to his gate.

The monster nods, tries to smile, and walks away.

Nobody has touched his face in 35 years, except healthcare workers. The salt on his cheeks makes them sting: the sun has made his face raw again. Even a little sunlight makes the old scars flare angrily. Tomorrow he’ll look more like a monster than ever. But by then it won’t matter, he’ll have returned to his usual ghost life, haunting his own small home. When he must go outside, he’ll be hooded.

Or perhaps not. Perhaps he just found what he was hunting for.

If a boy can see the man in the monster, maybe others can too.

Perhaps tomorrow he’ll be brave. Perhaps tomorrow he’ll step outside unhooded on an ordinary day, looking for others who can truly see.

Ω

Jaime Gill is a British-born writer living in Cambodia. His fiction and journalism have been published by Litro, The Guardian, BBC, Beyond Words, voidspace, Wanderlust, In Parentheses, and Write Launch. He consults for non-profits across Asia while working haphazardly on a novel, script, and far too many stories, several of which have been long/shortlisted for awards by titles including The Masters Review, the Bridport Prize and the Plaza Prizes. "The Monster and the Boy" will also appear in Literally Stories. Find him at www.twitter.com/jaimegill or www.instagramcom/mrjaimegill.

Hiokit Lao is a 29-year-old self-taught artist from NYC. Through surreal, abstract, and vibrant pieces, she aims to create meaningful art that instills hope and positivity. Employing different techniques, she creates pieces that offer dual perspectives, presenting dichotomous yet harmonious narratives based on the viewer’s orientation. When the canvas is inverted, a different narrative surfaces—a testament to the multifaceted nature of culture and perception.

It was just a fever / a strange Ophthalmia

by ELLEN JUNE WRIGHT

(for NH)

that spread among some & made them see / others’ lives as cheap commodities / cheaper than the price of tobacco when it falls / or hog bellies when they bottom out / This is not a racist country / This is simply our home sweet home / Jim Crow was just a nice old man / so no one was chased by dogs & mauled / & no one was spit on while sitting at a lunch counter / & no one was dragged from a jail cell / tarred / feathered & hanged from a poll / & no water fountains said FOR WHITES ONLY / & no Black entrances were ‘round back / & no swimming pool was drained after the touch of Dorothy Dandridge’s toe / No red lines were drawn around our neighborhoods / There were no towns with restrictive covenants / or Sundown towns / no Night Riders / no KKK / no supremacists / no woman sewed a white hood & cape / no crosses were burned / no churches were bombed / no one marched on Washington / & Bull Connor had no firehoses / & no child named Ruby was escorted to school by federal marshals / & the Little Rock Nine were welcomed with open arms / & Chaney / Goodman / & Schwerner are old friends rocking on a porch every evening as the sun sets / This was never a racist country / No highways destroyed Black communities / the path of least resistance / No Black towns were buried under lakes / & no fires blazed in Tulsa or Rosewood / ignited by lies / Rosa Parks did not train years to stay seated when the time came / & she never was arrested & fingerprinted / & no one threatened to bomb her house / or cut her throat / & Frederic Douglas was the first Black President / Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was the second / Medgar & Malcolm are about to be centenarians / & Emmett Till danced at his granddaughter’s wedding

Ω

Ellen June Wright is an American poet with British and Caribbean roots. Her work has been published in Plume, Tar River, Missouri Review, Verse Daily, Gulf Stream, Solstice, Louisiana Literature, Leon Literary Review, North American Review, Prelude, Gulf Coast, and is forthcoming in the Cimarron Review. She’s a Cave Canem and Hurston/Wright alumna and has received Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net nominations.

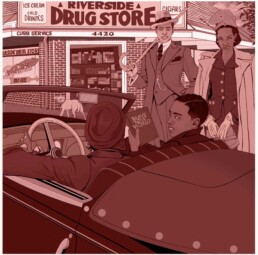

Lance Flowers is a Black multidisciplinary artist based in Texas. His work often tackles race, sociology, and satire through a lens of historical fiction. His audio work is in permanent collection at SFMOMA in collaboration with artist Rodney McMillian. His visual work has been recognized by institutions such as MFAH 5A and Texas Southern University. Flowers has also created album art for Stonesthrow Records. He is also a finalist for the Toni Beauchamp literary award.

'Til Death

by ALEX GOODSON

the truth is that

I couldn’t picture myself buried next to you

being in the ground together

is a lot more permanent

than a piece of paper from City Hall

maybe this is what we should talk about

when we talk about love

hey baby

do you want to dance

in the dirt with me?

push your hand through the packed soil

find my candlestick fingers

planted in the chilled earth

count my bones with kisses

as they sigh into dust

one by one

until only our skulls are left

the last guests to leave the party

(and we always left together)

turn to me, beloved

our teeth touch where our lips used to be

it sounds like knock knock

who’s there?

two skeletons

still in love

maybe this is what we should talk about

when we talk about love

Ω

Alex Goodson is a writer and poet who lives in Brooklyn with her dog, Bucatini. Her short story “The Art Show” appeared in the literary magazine Beyond Queer Words. She is a two-time Emmy-winning writer and producer for Good Morning America. She loves Joni Mitchell, 50/50 martinis, cooking, Tetris, and billiards.

Donald Patten is an artist and cartoonist from Belfast, Maine, who creates a unique range of artworks that are both visually striking and entertaining. He produces oil paintings, illustrations, ceramic pieces, and graphic novels. His art has been exhibited in galleries across Maine. His online portfolio is donaldpatten.newgrounds.com/art.

Cicadas

by DIRK FERGUSON | 1st Place, student prose contest

Your first memory is of trees. Later there would be your mother’s hands, running through your hair and braiding it as she hummed a song you still don’t know the name of. There would be your father and his friends drinking in the garage as you watched from behind a door. There would be long walks in the forest with your mother, the only times you saw her with trees behind your back in your young life before she started hating the forest. There would be the feeling of dirt kicking up and settling on your clothes as you played in the forest until dark. Birds would chirp in the early mornings, and you would hear the almost too-loud buzzing of cicadas in the summer. That all was later, though.

First, you remember the trees.

Rough, red bark scratched the palm of your soft, child hands. You remember looking up and up and up, craning your head to even just attempt to see the tops of the trees. Your eyes traced the patterns in the bark and in the leaves and tried to memorize the seemingly random markings. You were fascinated by something so much larger than you could ever be.

Birds chirped and cicadas buzzed, but all you could really focus on were the trees. They looked so tall to you back then. They looked tall enough to pierce the sky. You wanted to climb them and keep going until you reached the top and then stay there for the rest of your life. You almost did try, but you fell and didn’t make another attempt. Not that day, anyway.

You have loved nature ever since you could remember. There isn’t much else to love in the small town where you live, surrounded by too-tall redwoods as it is. You walk old and beaten paths in the forest as you grow up with these trees and become familiar with the sounds of nature. It becomes a comfort, after a while, after your family splits and your mother dies and your father is ready to drink himself into an early grave. It becomes a comfort because your town and your home even more is quiet. The silence is deafening; you could hear it if a pin dropped halfway across town. If you have hated anything since the moment you could begin to hate anything at all, you hated silence.

Something basic to consider: nature is not quiet.

It does not have the overstimulating mess of noise from a city or the white noise of an AC unit and a television talking in tandem that you might hear in a home. Nature is loud but not artificial and something about that has always comforted you.

As you grew up and got older and spent more and more of your time in nature, before she died, your mother started acting strange. She started telling you not to go into the forest.

She didn't like it when you went in alone among the tall redwoods. She never told you why, really, for what reason could she have for you to not go? When you grew up, no longer a child and still walking those old, beaten paths, you thought she just worried about you being alone. You were a child, and you were small and vulnerable. A coyote could have eaten you up without any problem. But later - but now, you mean - you started thinking something different.

Your mother wasn't afraid. But her rule of not going into the forest, which is a rule you have broken hundreds of times over by now, was not the afterthought of a distracted parent, either. She wasn't afraid but she was firm, and when you think back to those memories as a child of being scolded by her you can hear the overlaid sound of a cicada clicking softly against your ear.

"Don't go out there," she told you back then, "I told you to quit it. There's things out there you don't want to meet."

And you thought she meant the coyotes. Bobcats. Bears. The whispers of a cougar your father's friend swore he saw, he promised, it's out there. And maybe she did. And maybe she meant something else entirely, something that wasn't quite an animal, and you can't even ask. Your mother is six feet in the ground and your daddy is about to drink himself into a hole just like it and you can't ask.

II.

You were thirteen when your mother died.

It all seemed too sudden back then. Looking back, you think there were signs. She became paranoid too quickly, and it was a nightmare to interact with her even sparingly after a while. You don’t know what happened to her to make her act the way she did or why she became so insistent on you staying away from the forest. You still don’t know years later, even if you have more of an inkling.

Back then, you were thirteen and you were the one to find her body. Your memory of the afternoon when you found her, face down in the dirt of your driveway and fingers dug into the soil, and the morning of her funeral when you held your father's hand and stared stone-faced at her coffin is fuzzy. Still, you remember some things.

In the afternoon, your hair was down, and you can remember the way it tickled the back of your neck as you jogged from your friend’s house to your own. You hated the way it fell flat against your neck and brushed your shoulders when you stopped cold three feet away from your mother’s corpse. The way she was angled in the dirt made it look like she was trying to crawl towards the tall trees that make up the forest, like she was desperate to go back. In the morning, your hair was pulled back tight against your scalp, and there was a migraine building in your temples and behind your eyes. Your mother’s corpse looked peaceful and prettied up in the casket and you hated it. You remember the way your father sobbed, free hand covering his eyes with shame.

He loved her. And you loved her too, even under your building resentment, but after years pass the things you really remember most are the cicadas buzzing in the trees and thinking about how your mother always hated that sound.

When you go into the forest for the first time since the funeral, you can’t hear the birds calling or leaves whistling in the wind or the faint sound of water running in a creek. All you hear are cicadas year-round, buzzing and chirping, and sometimes it feels like they’re trying to sing to you, right in your ear. And sometimes it feels like they follow you home, and you can almost hear cicadas in your dreams.

III.

Your father gets more and more distant as time flies by. The two of you never were close, but these days it feels like you’re living with a stranger. He always smells like liquor even when he isn’t drunk, and the tirades he goes on are odd at the best of times and more often than not about your dead mother. Even just looking at you when he’s in a bad mood or drunk or both sends him off; you look too much like your mother for him to bear.

“You spend too much time out there,” he tells you with stumbling, slurred words on a bad night when you come back in the house from an evening walk. “Just like she did.”

You don’t dignify him with a response. It never ends well when you do, so you just let out a sigh as you hang up your jacket and slip off your shoes. You can see him lumber towards you in the corner of your eye and feel a stab of annoyance. You can’t wait to get out of this house.

“Don’t you ignore me!” he demands and grabs your wrist, grip loose but insistent.

You scowl at him and tug your arm away. “I can spend my time how I want,” you say.

The way your voice sounds to your own ears is whiny and petulant like a child instead of an almost-adult, but you can’t be bothered to care. These days when your father talks to you all you can hear is an unremitting buzzing in the back of your head, and all it does is remind you of your mother’s paranoid ramblings and her funeral and being too far into the forest at a time of night when you should be sleeping.

Your father snorts. He says, “You’ll end up like your mom,” and that stings more than it should. If there’s someone in the world you don’t want to be like it’s her, and he knows it.

God knows what he really means when he says things like that. You’re not sure if he knows more than he lets on, if he knows why your mother took a few too many pills and let herself pass out in the dirt the morning she died, or if he’s just spewing nonsense. You don’t get to ask because he shambles off to his bedroom without another word, and you can hear the echo of the door slamming shut from across the house. You’re not sure if you wanted to ask anyway. You’ve never had the courage to get the words out.

IV.

Your first memory is of trees, and you know that it will be your last memory too.

It seems so peaceful to die in nature. Others would disagree—others would say and have said to you it is better to die within the comfort of your own home. To die in a place that is familiar and safe and warm. No one wants to die out on the streets or in a hospital or, apparently, in a forest. But to you, along your well-worn and beaten paths, under the tall redwoods you have known your entire life, this is a place that is familiar and safe and warm and somewhere you would like to die.

After your mother died, you didn’t go into the forest for a while. It felt wrong, at first. Maybe you just wanted to listen to your mother’s wishes one last time, since you didn’t while she was still alive.

But something about it drew you back. Something about it always draws you back, and in retrospect, when you really sit down to think about it, it almost feels like you were being called. Which is a ridiculous idea and not one you usually entertain, but—

You lie in your bed, hands under your head, as you stare up at your ceiling. There is a cicada that sings into your ear constantly and you have heard it every single day of your life since your mother died. You can almost feel the soft weight of it barely noticeable on your shoulder and hidden in your hair. But you know it isn’t there. You’ve checked more times than you can count just today.

Something calls you to the forest. It’s not a person. But something calls you to the forest and left cicadas to bury themselves in your brain. And you have a sinking feeling your mother heard them too.

But would it be so bad to go? Would it be so bad to let yourself waste away and die, sitting underneath the trees you love so much?

You get off your bed and go to the bathroom to look in the mirror. Your hair is longer these days after years of not cutting it. You lift it to look at your shoulder, at your ears, and there is not a cicada there. You’ve checked so many times now, expecting a different outcome each time, but it’s always the same. There’s nothing there.

But you can hear that buzzing. You can hear it, echoing and bouncing off the walls and settling right into your brain. It’s the same sound you have heard all your life, and you want it to stop but at the same time—at the same time, it’s calling you.

You can see the forest from the bathroom window. You push away the curtains and look at it now, at the trees that sometimes seem so much taller than they should be, even for redwoods. The cicadas are louder than they have ever been, and they scream their songs to you, calling for you, begging for you.

You’re not like your mother. They called to her too, but she couldn’t make it back to the trees. She resisted too much. You’re not like her.

You go to the forest and follow the sounds of cicadas as they grow louder and become the only thing you know. The trees welcome you back and you know you will never leave again.

Ω

Dirk Ferguson is a TCC student currently studying English with plans to be a high school teacher. He is transgender and spends much of his free time writing and creating stories. He hopes one day to contribute to more LGBT+ representation in published books, especially in genres such as horror.

Emily Dangott is a student at TCC, where she is majoring in Communications. After TCC, she plans on attending the University of Oklahoma or the University of Central Oklahoma to continue her passion for photography. She has been a photographer for four years and will continue to work towards her career goal of becoming a fashion photographer. Her ultimate goal is to work for Vogue or Bazaar magazine. She currently works for several clothing boutiques in the Tulsa area, including J.Cole and Love Like Bean, and has an internship at Shane Bevel Photography.