Cicadas

by DIRK FERGUSON | 1st Place, student prose contest

Your first memory is of trees. Later there would be your mother’s hands, running through your hair and braiding it as she hummed a song you still don’t know the name of. There would be your father and his friends drinking in the garage as you watched from behind a door. There would be long walks in the forest with your mother, the only times you saw her with trees behind your back in your young life before she started hating the forest. There would be the feeling of dirt kicking up and settling on your clothes as you played in the forest until dark. Birds would chirp in the early mornings, and you would hear the almost too-loud buzzing of cicadas in the summer. That all was later, though.

First, you remember the trees.

Rough, red bark scratched the palm of your soft, child hands. You remember looking up and up and up, craning your head to even just attempt to see the tops of the trees. Your eyes traced the patterns in the bark and in the leaves and tried to memorize the seemingly random markings. You were fascinated by something so much larger than you could ever be.

Birds chirped and cicadas buzzed, but all you could really focus on were the trees. They looked so tall to you back then. They looked tall enough to pierce the sky. You wanted to climb them and keep going until you reached the top and then stay there for the rest of your life. You almost did try, but you fell and didn’t make another attempt. Not that day, anyway.

You have loved nature ever since you could remember. There isn’t much else to love in the small town where you live, surrounded by too-tall redwoods as it is. You walk old and beaten paths in the forest as you grow up with these trees and become familiar with the sounds of nature. It becomes a comfort, after a while, after your family splits and your mother dies and your father is ready to drink himself into an early grave. It becomes a comfort because your town and your home even more is quiet. The silence is deafening; you could hear it if a pin dropped halfway across town. If you have hated anything since the moment you could begin to hate anything at all, you hated silence.

Something basic to consider: nature is not quiet.

It does not have the overstimulating mess of noise from a city or the white noise of an AC unit and a television talking in tandem that you might hear in a home. Nature is loud but not artificial and something about that has always comforted you.

As you grew up and got older and spent more and more of your time in nature, before she died, your mother started acting strange. She started telling you not to go into the forest.

She didn't like it when you went in alone among the tall redwoods. She never told you why, really, for what reason could she have for you to not go? When you grew up, no longer a child and still walking those old, beaten paths, you thought she just worried about you being alone. You were a child, and you were small and vulnerable. A coyote could have eaten you up without any problem. But later - but now, you mean - you started thinking something different.

Your mother wasn't afraid. But her rule of not going into the forest, which is a rule you have broken hundreds of times over by now, was not the afterthought of a distracted parent, either. She wasn't afraid but she was firm, and when you think back to those memories as a child of being scolded by her you can hear the overlaid sound of a cicada clicking softly against your ear.

"Don't go out there," she told you back then, "I told you to quit it. There's things out there you don't want to meet."

And you thought she meant the coyotes. Bobcats. Bears. The whispers of a cougar your father's friend swore he saw, he promised, it's out there. And maybe she did. And maybe she meant something else entirely, something that wasn't quite an animal, and you can't even ask. Your mother is six feet in the ground and your daddy is about to drink himself into a hole just like it and you can't ask.

II.

You were thirteen when your mother died.

It all seemed too sudden back then. Looking back, you think there were signs. She became paranoid too quickly, and it was a nightmare to interact with her even sparingly after a while. You don’t know what happened to her to make her act the way she did or why she became so insistent on you staying away from the forest. You still don’t know years later, even if you have more of an inkling.

Back then, you were thirteen and you were the one to find her body. Your memory of the afternoon when you found her, face down in the dirt of your driveway and fingers dug into the soil, and the morning of her funeral when you held your father's hand and stared stone-faced at her coffin is fuzzy. Still, you remember some things.

In the afternoon, your hair was down, and you can remember the way it tickled the back of your neck as you jogged from your friend’s house to your own. You hated the way it fell flat against your neck and brushed your shoulders when you stopped cold three feet away from your mother’s corpse. The way she was angled in the dirt made it look like she was trying to crawl towards the tall trees that make up the forest, like she was desperate to go back. In the morning, your hair was pulled back tight against your scalp, and there was a migraine building in your temples and behind your eyes. Your mother’s corpse looked peaceful and prettied up in the casket and you hated it. You remember the way your father sobbed, free hand covering his eyes with shame.

He loved her. And you loved her too, even under your building resentment, but after years pass the things you really remember most are the cicadas buzzing in the trees and thinking about how your mother always hated that sound.

When you go into the forest for the first time since the funeral, you can’t hear the birds calling or leaves whistling in the wind or the faint sound of water running in a creek. All you hear are cicadas year-round, buzzing and chirping, and sometimes it feels like they’re trying to sing to you, right in your ear. And sometimes it feels like they follow you home, and you can almost hear cicadas in your dreams.

III.

Your father gets more and more distant as time flies by. The two of you never were close, but these days it feels like you’re living with a stranger. He always smells like liquor even when he isn’t drunk, and the tirades he goes on are odd at the best of times and more often than not about your dead mother. Even just looking at you when he’s in a bad mood or drunk or both sends him off; you look too much like your mother for him to bear.

“You spend too much time out there,” he tells you with stumbling, slurred words on a bad night when you come back in the house from an evening walk. “Just like she did.”

You don’t dignify him with a response. It never ends well when you do, so you just let out a sigh as you hang up your jacket and slip off your shoes. You can see him lumber towards you in the corner of your eye and feel a stab of annoyance. You can’t wait to get out of this house.

“Don’t you ignore me!” he demands and grabs your wrist, grip loose but insistent.

You scowl at him and tug your arm away. “I can spend my time how I want,” you say.

The way your voice sounds to your own ears is whiny and petulant like a child instead of an almost-adult, but you can’t be bothered to care. These days when your father talks to you all you can hear is an unremitting buzzing in the back of your head, and all it does is remind you of your mother’s paranoid ramblings and her funeral and being too far into the forest at a time of night when you should be sleeping.

Your father snorts. He says, “You’ll end up like your mom,” and that stings more than it should. If there’s someone in the world you don’t want to be like it’s her, and he knows it.

God knows what he really means when he says things like that. You’re not sure if he knows more than he lets on, if he knows why your mother took a few too many pills and let herself pass out in the dirt the morning she died, or if he’s just spewing nonsense. You don’t get to ask because he shambles off to his bedroom without another word, and you can hear the echo of the door slamming shut from across the house. You’re not sure if you wanted to ask anyway. You’ve never had the courage to get the words out.

IV.

Your first memory is of trees, and you know that it will be your last memory too.

It seems so peaceful to die in nature. Others would disagree—others would say and have said to you it is better to die within the comfort of your own home. To die in a place that is familiar and safe and warm. No one wants to die out on the streets or in a hospital or, apparently, in a forest. But to you, along your well-worn and beaten paths, under the tall redwoods you have known your entire life, this is a place that is familiar and safe and warm and somewhere you would like to die.

After your mother died, you didn’t go into the forest for a while. It felt wrong, at first. Maybe you just wanted to listen to your mother’s wishes one last time, since you didn’t while she was still alive.

But something about it drew you back. Something about it always draws you back, and in retrospect, when you really sit down to think about it, it almost feels like you were being called. Which is a ridiculous idea and not one you usually entertain, but—

You lie in your bed, hands under your head, as you stare up at your ceiling. There is a cicada that sings into your ear constantly and you have heard it every single day of your life since your mother died. You can almost feel the soft weight of it barely noticeable on your shoulder and hidden in your hair. But you know it isn’t there. You’ve checked more times than you can count just today.

Something calls you to the forest. It’s not a person. But something calls you to the forest and left cicadas to bury themselves in your brain. And you have a sinking feeling your mother heard them too.

But would it be so bad to go? Would it be so bad to let yourself waste away and die, sitting underneath the trees you love so much?

You get off your bed and go to the bathroom to look in the mirror. Your hair is longer these days after years of not cutting it. You lift it to look at your shoulder, at your ears, and there is not a cicada there. You’ve checked so many times now, expecting a different outcome each time, but it’s always the same. There’s nothing there.

But you can hear that buzzing. You can hear it, echoing and bouncing off the walls and settling right into your brain. It’s the same sound you have heard all your life, and you want it to stop but at the same time—at the same time, it’s calling you.

You can see the forest from the bathroom window. You push away the curtains and look at it now, at the trees that sometimes seem so much taller than they should be, even for redwoods. The cicadas are louder than they have ever been, and they scream their songs to you, calling for you, begging for you.

You’re not like your mother. They called to her too, but she couldn’t make it back to the trees. She resisted too much. You’re not like her.

You go to the forest and follow the sounds of cicadas as they grow louder and become the only thing you know. The trees welcome you back and you know you will never leave again.

Ω

Dirk Ferguson is a TCC student currently studying English with plans to be a high school teacher. He is transgender and spends much of his free time writing and creating stories. He hopes one day to contribute to more LGBT+ representation in published books, especially in genres such as horror.

Emily Dangott is a student at TCC, where she is majoring in Communications. After TCC, she plans on attending the University of Oklahoma or the University of Central Oklahoma to continue her passion for photography. She has been a photographer for four years and will continue to work towards her career goal of becoming a fashion photographer. Her ultimate goal is to work for Vogue or Bazaar magazine. She currently works for several clothing boutiques in the Tulsa area, including J.Cole and Love Like Bean, and has an internship at Shane Bevel Photography.

3.15

by SARA ROSE HOTALING

time is wholly unconcerned with the demands of the soul.

a body moves through the day

i suppose it even gets through the night

but my spirit

is in the same room.

do you know the room?

the transparent walls are stained gray

a chapel with its vitality engulfed and estranged

do you know this room?

there’s a dentist

a chair

a body i suppose is my own

there’s numbing gel on my hippocampus

there’s floss between my heart strings

in the timeless dentist chair i see all

i see life go on

and on

and i am motionless.

with a bib on my chest and a hand in my mouth

a feeling beyond discomfort

have u ever had someone deny you closure?

what am i

but a mind stuck in a room

watching life go on

maybe tomorrow there’ll be a door.

Ω

Sara Rose Hotaling is an undergraduate student at Old Dominion University pursuing a BA in English with a concentration in Linguistics and a minor in French. She has conducted, presented, and published research that analyzes conceptual metaphor usage in political campaign discourse. In addition to linguistics, Sara Rose has an interest in literary criticism, critiquing classic works from authors such as William Shakespeare and Nathaniel Hawthorn from both a queer and feminist perspective. Finally, she is a poet who enjoys visceral, earthy, stream-of-consciousness writing interwoven with écriture féminine.

Michael Hower is a photographer from Central Pennsylvania, where he resides with his wife and two boys. His work has been featured in shows at the Biggs Museum of Art, the Masur Museum of Art, the Fitton Center for Creative Arts, the Penn College, and the State Museum of Pennsylvania.

Two Houses

by ISABELLA DOEKSEN | Sarah Stecher prize, student poetry contest

In my Mother’s home

Mere Christianity & The God Delusion

Share a shelf

She got the former

From my Grandfather

The latter

From leaving

Personally

I think Richard Dawkins & C.S. Lewis

Are both too condescending

To take seriously

I was born in two thousand & four

But I grew up on cassette tapes

In my Grandfather’s home

If you blow on the spindles

& the tape gently

Sometimes

You can stop them

From catching

I didn’t have the patience for

Beethoven’s fifth symphony

So I listened

To “Adventures in Odyssey”

They’re much more in line

With C.S. Lewis’s

Brand of proselytizing

but Goddamn if they weren’t entertaining

All ham-fisted sanctimony

& action-figure Messiahs

All fire & brimstone

& scare-crow nonBelievers

Thrown unto the pyre

I grew up a tomboy

Runnin’ around in gym shorts

& oversized t-shirts

On my Grandfather’s dirt

But tomboys don’t grow

Into tomMen

I may be built like a stick bug

but Goddamn if I wasn’t

A stumbling block

My Mother’s voice is in my ear

In my Grandfather’s home

Telling me to put a training bra on

Under my dry-fit Nike t-shirt

Because there’s no way in Hell

Grandma would ever think

of disinviting Uncle ****

Eventually

They bought me CDs

Eventually

I started wearing a 32 A cup

that I got from my mother

Eventually

I learnt that “Focus on the Family”

is considered a hate group

by the Southern Poverty Law Center

Eventually

I stopped listening

to “Adventures in Odyssey”

Learnt what I needed to

From leaving

but my Mother still gets their magazines

Espousing the virtue

Of one-piece swimsuits

To prepubescent children

Goddamn

Ω

Isabella Doeksen is a high school senior who is dual-enrolled at TCC. She plans to graduate in May.

Xitlalli Ruelas Sandoval is a self-taught artist and student at TCC currently pursuing a degree in Graphic Design. Making art has always been one of her biggest passions. She won Best in Show in the 2022 George Miksch Sutton art contest. Participating in artistic opportunities has allowed her to expand her experience and dedication towards her work and audience.

Opossum

by ZACH MURPHY

Pete and Richard’s orange safety vests glowed a blinding light under the scorching sun, and their sweat dripped onto the pavement as they stood in the middle of the right lane on Highway 61, staring at an opossum lying stiffly on its side.

Richard handed Pete a dirty shovel. “Scoop it up,” he said.

Everything made Pete queasy. He once fainted at the sight of a moldy loaf of bread. Even so, he decided to take on a thankless summer job as a roadkill cleaner. At least he didn’t have to deal with many people.

Richard nudged Pete. “What are you waiting for?” he asked.

Pete squinted at the creature. “It’s not dead,” he said. “It’s just sleeping.”

“Are you sure?” Richard asked as he scratched his beard. He had one of those beards that looked like it would give a chainsaw a difficult time.

“Yes,” Pete said. “I just saw it twitch.”

Richard walked back toward the shoulder of the road and popped open the driver’s side door of a rusty pickup truck. “Alright, let’s go.”

Pete shook his head. “We can’t just leave it here.”

“It’s not our problem,” Richard said. “They tell us to do with the dead ones, but not the ones that are still alive.”

Pete crouched down and took a closer look. “We need to get it to safety,” he said.

Richard sighed and walked back toward the possum. “What if it wakes up and attacks us?” he asked. “That thing could have rabies.”

“I don’t think anything could wake it up right now,” Pete said.

Richard belched, “It’s an ugly son of a gun, isn’t it?”

“I think it’s so ugly that it’s cute,” Pete said.

“No one ever says that about me,” Richard said with a chuckle. “I guess I just haven’t crossed into that territory.”

Just then, a car sped by and swerved over into the next lane. Pete and Richard dashed out of the way.

“People drive like animals!” Richard said. “We’d better get going.”

Pete took a deep breath, slipped his gloves on, gently picked up the opossum, and carried it into the woods.

“What are you doing?” Richard asked. “Are you crazy?”

After nestling the possum into a bush, Pete smelled the scent of burning wood. He gazed out into the clearing and noticed a plume of black smoke billowing into the sky. The sparrows scattered away, and the trees stood with their limbs spread, as if they were about to be crucified.

“Jesus Christ,” Pete whispered under his breath.

Pete picked up the opossum and turned back around.

Ω

Zach Murphy is a Hawaii-born writer with a background in cinema. His stories appear in Reed Magazine, Still Point Arts Quarterly, The Coachella Review, Maudlin House, B O D Y, Litro Magazine, Eastern Iowa Review, and Flash: The International Short-Short Story Magazine. His chapbook Tiny Universes (Selcouth Station Press) is available in paperback and ebook. He lives with his wonderful wife, Kelly, in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Josephine Florens is a professional oil painter. She was born in Odessa, Ukraine, but lives in Bad Grönenbach, Germany, as there is a war going on in Ukraine. She graduated from Odessa National Academy of Law with a Master's degree in Civil Law and from Odessa International Humanitarian University with a Master's degree in International Law. She started painting in 2017 and studied individually at the Art-Ra school of painting. She is a member of the National Association of Artists and Sculptors of Ukraine, the Odessa Marine Union, Ukraine, and an honorary member of the Union of the World’s Poets and Writers.

Moonflower

by ALI SEIBAL | 2nd Place, student poetry contest

I bloom with the shy flowers of the dark

Finding solace in the silence of midnight

I unfold pieces of myself

In broken strips of moonlight

My petals unfurl with seeking hands

Touching the shadows in gentle caresses

They keep my bones from breaking

Cleaning up my salty messes

I am fragile in the dark

My shadows watch me wither

Waiting for the sun to rise

To watch me wilt and shiver

Waiting for the sun to rise

My shadows watch me wither

I am fragile in the dark

Cleaning up my salty messes

They keep my bones from breaking

Touching the shadows in gentle caresses

My petals unfurl with seeking hands

In strips of broken moonlight

I unfold pieces of myself

Finding solace in the silence of midnight

I bloom with the shy flowers of the dark

Ω

Kathy Bruce is a visual artist based in New York and Scotland. Her collages explore archetypal female and mythological forms within the context of poetry, literature, and the natural environment. She has exhibited in the US, UK, and internationally, including Senegal, Taiwan, France, Denmark, Peru and Canada. Her collages have appeared in Three Rooms Press, Vassar Review, The Perch Yale University, Variant Literature, Rejoiner, Brooklyn Review, Twyckenham Notes, Porter House Review, and U.S. National Women’s History Museum Journal.

No One Need Know

by MELVIN EINHORN

My boss, Arthur, was innovative and magnetic. I learned that he composed the ad which attracted my interest. It was brief yet potent, described a hypothetical candidate, and invited the person for a telephone interview to discuss requirements.

Arthur defied convention. He removed the barriers imposed by human resources professionals to cull out undesirable candidates and marketed as if there were a buyer and a seller. When I returned his message, he noted the advantages of convenient public transportation, the location adjacent to Central Park, hospital housing, and the walkable distance to Upper East Side housing (where I resided). The excitement of a medical center revitalizing research facilities, advanced medical facilities, the unique concept of a hospital building its own medical school were to me purposeful and magnetic. A system where people came to clarify miffing diagnoses and address breakthroughs.

The salary and benefits were excellent. The business purposes were not sterile like the downtown designer-hewn enterprises. Fortunate for me, he was open to trying a Dictaphone rather than insisting on shorthand.

The setup of his office was unique. His desk was small, nestled inside a semicircular tabletop apron with legs, which seated six. Matching waist-high shelves, mounded with thick folders, lined three walls; there were two corner coves, each with a small, gray, upholstered barrel chair. Unlike an office where the authority of the owner was not to be questioned.

An insecure visitor could be coddled in a corner. I was relieved to be arm’s length from Arthur. He sat a chair away from me opposite his catbird high-back desk chair. I had come early and had coffee in the cafeteria. When I mentioned to the gossipy, curious older woman who sat down next to me that I was having an interview with Arthur Swift, she cackled and said, “He’s the head Director of the Personnel Police.”

He conveyed a different impression. In his office he oriented me to the various functions contained within human resources using thumbnail summaries. As he presented his domain, he proudly identified a chronology of individuals he had promoted.

When I shared highlights of my work history, he reacted favorably. We conducted a dry run dictation on a Dictaphone he had borrowed. He approved. He looked me over respectfully. I think my attractive appearance helped. Modestly attired in office casual, I wore a cardigan sweater over a high-neck blouse to conceal my buxom chest and come across as reserved.

I lived alone in a luxury high-rise one-bedroom on the Upper East Side near Yorkville, a German-American neighborhood. When I mentioned I might walk to work, Arthur brought to my attention a custom ideated by several women in his department. No matter how one got to work, it was helpful to wear sneakers and change to shoes upon arrival.

He told me the workplace encouraged participation but eliminated a suggestion system with monetary rewards as a discouragement to teamwork. He noted that he led a successful effort to discontinue exit interviews. He instituted collection of feedback in a follow-up meeting after completion of the standard three- or six-month introductory period (no longer called probation). The process was run by a joint team of social workers, human resources trainers, and second- and third-shift nurse managers. Employees were asked to anonymously compare previous employment scenarios and our facility, identifying desirable and undesirable reactions toward behaviors and rules.

I spoke up. “I like to participate. It makes perfect sense that someone no longer committed to an employer may trash her supervisor, might hold back, concerned her reference might be impacted, be indifferent. The coordination of line and staff input does away with the ugly regulatory label human resources gets, weakens lobbying by staff supervisors, and bares extreme behavior by leaders who may be the cause of turnover. Arthur, I read the article you wrote, in the college library when I went to apply for readmission. ‘Straightforward and measurable.’ I would like to be part of a process like that.”

He smiled broadly. “Our departmental budget is earmarked to spend a generous amount on training and development, with tuition reimbursement for our workforce. Your orientation will be interactive, not a series of lectures by busy volunteers. Next you and I will meet to discuss our quirks and preferences.”

I asked him to name one. He said, “I want my phone answered in three rings or less. You and I share lines. I don’t like to put calls on speaker. I prefer to interrupt what I am doing, including a meeting, excuse myself to whomever is with me, and dispense with the call with brevity or set up a call back. Why fail to pay heed to calls for help? Some people dislike this. I think it’s better than turning aside what may be stat, our word for a higher priority. How do you feel about that?

“If my wife calls when you are in my office, I would like to respect our exchanges. You will not know what she wants. I want to be able to trust you. You may be concerned with what I say to her. Please assume I will wave at you to go if I am concerned. She and I have different priorities except where it concerns the children.”

Two delightful years went by. I had taken over parts of Arthur’s hands-on role in new employee orientation. My attendance at meaningful training and development evening courses led me to matriculate, and I gained a deeper understanding of the field. I was taught how to design and present programs.

The Sensitivity Training for Managers and Employees in-house program (STME) was set for a weekend away at the Hotel Thayer. Dr. Miller, an industrial psychologist, and his partner were the facilitators. The pilot group was human resources managers reporting to Arthur.

Arthur motioned me into his office. He was frequently upbeat, smiling, and lighthearted. It was contagious and became a predictable aspect of the persona of new hires reporting to him.

“Dr. Miller made a recommendation which I thought I’d run by you. He reminded me that the STME program is designed to improve the dynamics between employees and managers, and we discover what you are good at as well. It is an informal activity where there is no superior and subordinate relationship, so perhaps we should broaden the list of invitees and invite you and a few other key associates.”

I tend to surprise people with my insight. I noted these goals on my pad. I was thrilled to join the select group. Arthur was sensitive to body language and hesitations which are not apparent to others. He reacted to the calmness of my answer. I was thinking of his role. He liked to evaluate trainers in the classroom. I thought evaluating Dr. Miller in action needed special handling. Was it intended that Arthur be an evaluator-note-taker or a participant in the various small group breakouts, subject to the facilitators’ control? is H

Arthur loved my question. Arthur with Dr. Miller’s approbation was to be a participant, and that wase was ratified by the group of sixteen, by secret ballot.

The sessions were long and emotional. The group members were advised to keep aside their own prejudice or opinion about the other members so they did not sound judgmental. Once a member gained the confidence to speak freely about whatever was on her/his mind, interactions started to take place. People began to realize how other people perceived each other and themselves.

Dr. Miller asked the group after dinner in if they wanted to keep the session going to midnight or go to the bar and grill in Woodbury and chill out. He looked at Arthur, and Arthur shook off the opportunity to comment. It appeared to me Dr. Miller wanted the group to keep talking. I looked around. I was exhausted though I was mindful. I was bothered by the paucity of breaks, and others looked antsy too. The decision to have a secret ballot vote was well received. With no dissenters, we went to the bar.

The Sunday tours and walkabouts around the West Point campus were scenic and inspiring. I was in an enviable position to observe Arthur’s personal dilemma, his wife and family. He appeared to be a loving and attentive father, though he seemed resigned to avoid disrupting his children by divorcing his wife. His diversions with female protégés were obvious to me but unseen or overlooked by others. The protégés were dazzlingly bright and accomplished and merited praise.

These escapades seemed to be risky and questionable, could damage his reputation for impartiality. He kept his bitterness well concealed to others. But had he painted himself into a corner? It pained me not to be able to help him, not neglect my own concerns or make things even worse. My attendance at the workshop uncovered intense feelings for Arthur on my part. I felt even closer to him. In our exchanges, he seemed more compassionate and paternal toward me.

I had an intricate problem. The amorphous structure of the training at its outset brought forth raw chaos, and it did not dispel. Worse was the feedback from others, which was hard to take. I realized that I was hard to read. I did not realize that detracted from my acceptance. I was concealing a terrible experience with bizarre fallout. I was a haunted runaway.

No one from work had seen my apartment, which would have raised a question of how I could afford the rent in such an upscale building without a roommate. My parents sold the Amenia Farm and Rehabilitation Center in Ulster County after I was knocked unconscious, severely beaten, and raped. The culprit(s) undetected. I was legally granted a new identity like the FBI used in protecting an informant. A single-occupancy apartment in the single-ladies-only Barbizon Hotel in midtown Manhattan was leased for me by my parents.

It took a year for plastic restoration of my palate and broken face bones and teeth, and for me to complete therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder at an elite residential unit in an expensive private hospital run by the east side Cornell Medical Center.

A troubling stress-related byproduct was the involuntary tightening of my pelvic floor muscles preventing entrance into my vagina. I couldn’t use tampons. Sexual intercourse was impossible. There was nothing to forget, no guilt. Most non-virginal rape victims react by being less interested in resuming intercourse. I was more interested.

I met a potential boyfriend in rehabilitation. Monty was ex-military. He walked away from a job on Wall Street as a stockbroker with substantial wealth and enlisted. He had PTSD from combat experiences.

Vera, my sex therapist, took me through Kegel exercises, stress management, and relaxation protocols, dilation, and finally offered to coach me and a lover in how-to sessions in foreplay to build an enabling trust. She volunteered to be in the room to direct foreplay. I did not feel ready, though Monty was sincere and willing. Vera was a religionist. Her zeal led her to compare my mindset to purgatory, which she described as a “lingering forever.” She was daunted in our discussion when I pointed out that I had no sin to cleanse, felt no guilt, yet was shamed by involuntary contractions of my entrance.

She even suggested playing Shostakovich symphonic music, which was broadly tonal and had a colossal tonality and purgatorial numbness to it. I listened to several recordings, and it was powerful and saddened me. Frank Sinatra struck me as invasive.

It did make sense to me to try it with a partner. Monty tried to reassure me, not to worry, by explaining that he would be able to get it up with a third person present. But what if he couldn’t? That would add him to the problem. Would we need a coach to be present more than once? Monty was growing on me. He wanted to be married again. I was uncomfortable making him a guinea pig. This was not a normal circumstance.

Relating to others without fully understanding how they saw me was a dilemma I now put in the spotlight. I didn’t realize until the sensitivity exercises that my soul was invisible. I expected to gain confidence and become more inquiring of others, though when the shoe was on the other foot, I was withholding and thought being seen as young, pretty, diligent, reliable was enough.

I loved the way Arthur chose to interface with me. He didn’t interfere or override. His kindness was familial. He held mirrors up for me to question myself. I loved his intention but had missed opportunities to be close to him, beyond my daydreams. I certainly didn’t want to drive him away with a risky witnessed experiment or a clumsy seduction.

“No one need know,” my inner voice whispered. “Including Monty,” it added.

I wanted to bond with Arthur, be intimate in extended detail before I moved on with my life. I sensed Arthur could benefit as well. I would lead him from the fabricated patchwork of lovers he was treading upon. He could use our close encounter to improve his approach to a sexual relationship with me, rescue a woman he trusted and deserved. He needed to be inspired by someone like me, even though I may not be worthy of him.

Monty need not know. He could still be my man. We could seek a safe, quiet life together, maybe move to Virginia to be near my parents. He joked that he would have to sell our building first. He was terrified that he would not be a good father, and I was nervous to be a mother. I could pick Arthur’s brain about parenting.

My notion that Arthur and I could help each other was not something to discuss at a bar. He was coming in to work next Saturday morning to observe the attendance of an assistant manager. The man was Asian American. His boss told Arthur that Asians were exceptional at math and could be trusted to work unsupervised; that his work would be verified by a record review.

Arthur was bringing his three-year-old son. I don’t want to appear to be smug, but Arthur was done early. The man was not there at all. Arthur did not condone ethnic bias, for or against. He was also not complacent about fraud.

I heard Arthur telling his wife on the phone he would be taking their youngest son to the Central Park Zoo to go on the historic carousel nearby. I expected that I could easily convince Arthur to let me go along, or I could implement the rest of my plan the following week.

I would tell him I had a personal matter I wished to discuss that would be more comfortable for me to do in fresh air. If that didn’t fly, I would try to get him to hear my agenda over dinner at my place the following Tuesday evening, since he was free then.

I’d tell him about the blind rape, my new identity and relocation, Monty, and my post-traumatic vaginitis. That Monty was the doorman and security person at my building. We met in rehab; they placed him there on a trial basis, and he was hired. When I came out of my coma, and they repaired my mouth, I finished recovery and wanted to leave the Barbizon for Single Ladies but stay on the East Side. Monty suggested my current building, where he could keep an eye on me. Nobody knew we were seeing each other.

The zoo, the carousel, his little boy a gem, and dinner at my place on Tuesday. Arthur arrived with a bouquet and pastries from the German bakeshop. Dinner, halibut, steamed vegetables, small salads. Robust Turkish coffee. I was almost done. Did he need a rationale?

“You could say yes and justify it as supporting my fantasy. Or just make it into our fantasy. I learned from the sex therapist about ways to perform foreplay and unlock my rape-induced vaginal panic seizures. I have an option, bring someone to a sex trial with me. The sex therapist, Vera, in person, could coach us. You or Monty, but with either of you, there are also drawbacks.” He waved that off.

“And/or?” he said, urging me to continue.

“Arthur, I may be wrong. Watching you suffer, clinging to your marriage like it was a stillborn baby, has been painful.”

“There was a stillborn baby boy. Not something I want to talk about.”

“I’m so sorry. I observed you scratching, and it wasn’t just a seven-year itch. You don’t look well wearing bitterness. I can sense your frustration, screwing more women with less delicacy, until you are hanging on to passion by a thread.”

“You want to teach me how to make love softly, and before I lose whatever touch I can muster, help you to regain your touch?”

“Before we lose hope, Arthur!”

“The password open sesame unblocked the mouth of a cave where forty thieves buried a treasure. But I am Arthur Swift, not Ali Baba.”

Ω

Melvin Einhorn’s first voluminous rejection by a noted NYC publisher was a triumph for his creative writing instructor. Melvin was seventeen. An ornery but sensitive cuss, he graduated to thrive at work in healthcare industrial relations. Women proved to be incomprehensible to him; he gingerly returns insignificant as a fly on the wall to bravely write this story from a woman’s perspective. He vowed to be published and keep going. Bless you, Tulsa Review. Eighty-three is not too old.

Emily Dangott is a student at TCC, where she is majoring in Communications. After TCC, she plans on attending the University of Oklahoma or the University of Central Oklahoma to continue her passion for photography. She has been a photographer for four years and will continue to work towards her career goal of becoming a fashion photographer. Her ultimate goal is to work for Vogue or Bazaar magazine. She currently works for several clothing boutiques in the Tulsa area, including J.Cole and Love Like Bean, and has an internship at Shane Bevel Photography.

A Better Place

by JAMIE CUNNINGHAM | 2nd Place, student prose contest

Anna May was the eldest member of the little Cherokee community called Pin Oak and was something of a spiritual leader to those in the neighborhood. She was known as Pin Oak’s Beloved Woman, a position of respect. A position Anna May relished ever since her older cousin, Lucy Buck, succumbed to stomach cancer five years ago and the honorific fell to Anna. As Beloved Woman she was often the center of attention during holidays when everyone migrated to her house for Christmas breakfast or Independence Day cookouts. At such events, Anna’s exquisite frybread was usually the centerpiece. In addition, as eldest of the elders, she was often consulted in the domestic affairs of her neighbors which fed her girlish obsession for gossip.

They found Anna May after the quarantine. After no one had heard from her for almost three days. They found her on the kitchen floor barely conscious and talking in a soft voice, though she was mostly incoherent. Someone said it sounded like she was praying. Someone else said it sounded like a cooking recipe. The EMTs, both yonega —white folk—mistook Anna’s lilting Cherokee as the gibberish of a dying old woman.

It was Tina’s boy Charles, the husky one, who found Anna May that day. Charles—the kids all called him Roundboy—was notorious for showing up unannounced and uninvited wherever he thought a meal might be found. His poor mother did her best to keep him fed at home, but Roundboy’s stomach was seemingly boundless, so he often spent time after school roaming around Pin Oak looking for snacks. While other kids played tag or hide-n-seek, Roundboy foraged through his neighbor’s cupboards. Over time, the boy’s behavior, cute and endearing when he was five, had become a way of life for those in Pin Oak. At least he wasn’t a finicky eater and was easily satisfied with a plain bologna sandwich. It was Roundboy’s appetite that lead him to Anna May’s that fateful day, hoping for a piece of her famous frybread.

Roundboy grew up with Anna May’s cooking and knew she always kept a basket of bread on her stove, just in case of unexpected visitors. Among those of Anna’s generation it was customary to offer food to anyone who entered the home. Whether a pauper or the President, if you entered Anna May’s house, you were expected to partake in whatever tasty morsels she might have available. Even the meter man knew this custom well and scheduled his visits to Anna’s house just in time for lunch. It was considered a great insult to decline such an offer. But on that unfortunate day after the lockdown, Roundboy was distraught to find no frybread on the stove and Anna May crumpled on the kitchen linoleum.

Due to the pandemic, the funeral for Pin Oak’s late Beloved Woman was not as grand as Anna May would have hoped for, but it still violated CDC recommendations for such gatherings, which would have delighted the mischievous old woman. As tradition dictated, her body was presented in the living room of her home so family and friends could pay their respects, swap stories, and eat. In better times this celebratory wake might last for three days, but due to travel restrictions the reception was smaller than expected. The funeral home picked up Anna after just a day. The funeral was held graveside so the attendees could distance themselves if they wanted. Some did, maintaining six feet of space. It did not go unnoticed to the Pin Oak mourners that they were six feet above their ancestors, as well.

The eulogy, and even much of the service, was held in the Cherokee tongue. As the preacher spoke in his soft, stilted English, a dialect common among the dwindling elders, the old ones nodded stoically as the younger generation listened with reverence. Anna May’s nieces sang ‘Amazing Grace’ in Cherokee; the syllables memorized because they do not speak the language of their people.

Once Anna May was lowered into the ground, a procession of mourners lined up to toss a handful of dirt into the hole. Nearby, a county worker sat on a backhoe waiting to finish the job. As the bereaved made their way past the family members seated near the grave, they paused to shake hands and offer condolences. At the end of the row was Anna May’s younger sister Nan who bore her grief in silence, nodding to the well-wishers as they passed by. After everyone left, Nan remained, alone, staring at the treetops and reflecting on life. Her big sister was gone. Somehow, this fact both frightened and comforted her. One thing on Nan’s mind was, who would she talk Cherokee with now? When she finally rose from her chair, she heard the backhoe fire up. She gave the gravedigger a little wave, and he nodded back in obeisance. Now, Nan was Beloved Woman.

One the day the ambulance came for Anna May, Nan had been out in her garden. She heard the sirens fade and crescendo in the distance as the first responders weaved through the valleys along roads that twisted like ribbons of asphalt. Pin Oak is tucked into the woody Ozark foothills near the Oklahoma/Arkansas border. Approaching emergency vehicles can be heard for miles before they’re ever seen. Tina, who lived next door to Nan, came running over when she heard the dire news, and the pair waited nervously amid the tomato plants for the ambulance to arrive. When the orange and white van entered Pin Oak it shut off its alarms and rolled silently through the neighborhood as the curious peeked out their windows, holding their breath and wondering who was hurt or sick or in distress. Soon after, Roundboy came huffing and puffing up the road with a scared look in his eyes. In Nan’s garden he updated the women on Anna May’s condition, clinging to Tina like a toddler. Nan gave him a cucumber to chew on so he would calm down.

As the ambulance was leaving, Nan flagged them down. One of the EMTs recognized Nan and paused so the two women could talk. Nan, still nimble in her late-sixties, hopped up into the back and grabbed Anna’s bony hand. Anna, more lucid than before, smiled to her sister and motioned for her to come closer. Obediently, Nan laid her head on her big sister’s shoulder just as she did when they were little girls.

“Sister, are you okay?” Nan asked.

In Cherokee, Anna May whispered a touching elegy, ending with this declaration: “Dvganigisi”—I’m going home.

Nan had Tina drive her to the Indian hospital in Tahlequah, and later that night Anna passed away quietly and peacefully; not from any virus, but from an embolism, something no quarantine could keep out. Out in the cold hospital waiting room, Nan wept quietly. Though surrounded by her children she suddenly felt alone. She wanted to tell them what Anna May had whispered to her, Anna’s last words, but no one would understand. Though they were her family, they cried in English. When Nan grieved, it was in her mother’s tongue.

For the week following the funeral, Nan spent her days in her garden, a simple plot bound by a wire fence meant to keep out the deer and other critters. She busied herself by pulling weeds, shooing away blackbirds, and bickering with the rabbits. From the kitchen window Tina kept a wary eye on the elder woman and worried about her. Nan took Anna’s passing with enduring grace, but Tina was certain Nan must be breaking inside. Several times a day she called to see if Nan needed anything. She never did.

One morning Nan was in the garden when she received a visit from John, the best friend of her son Tommy. As teens the two boys were inseparable, chasing girls, drinking beer, and playing music; Tommy played the drums and John the guitar. As the boys transitioned into men, they began to spend more time playing the radio than their instruments. Sadly, Tommy died five years earlier, either from the diabetes or the booze, depending on who you asked. Since then, John had become a regular at Nan’s dinner table. To her, he was another son.

“Osiyo,” John greeted her as he came through the squeaky metal gate.

“Siyo, chooch.” She was sitting in the shade of a nearby oak with her paisley-patterned garden gloves folded on one knee. Nan smiled and brushed some dirt from her pants then pointed to some plants. “Those t’matoes are gettin’ kinda weedy.”

That was how Nan was. She would never outright ask you to do something. Instead, she simply pointed out a thing that need to be done, and it was implied that it was the responsibility of whomever was within earshot to get it done. John was half Cherokee himself, his long deceased mother a full-blood, so he was familiar with this peculiar tactic. It was a tradition of sorts that he’d failed to pass down to his own son. Maybe it only worked for mothers. John smiled and made his way toward the offending vegetation.

“Where you been, stranger?” Nan asked as she fished a saltshaker from her pocket. John had been noticeably absent since the pandemic began.

“Stuck in quarantine with a gal in Tulsa,” he said while tugging at a stubborn weed. “She had a nice kitchen, but she couldn’t cook. Sorry I missed Anna May’s funeral.”

“Osi,” she said with a little wave. It’s okay. “Sister didn’t notice. Funerals are so boring anyway. You hungry? There’s some eggs and frybread from breakfast on the stove.”

“I stopped at McDonald’s.”

Nan frowned at the notion of fast-food, then looked around her garden. “I need a couple good cucumbers, two t’matoes, and some lettuce if the rabbits haven’t chewed it all.”

John turned to inspect the produce. He chose two plump heirlooms and some fat cucumbers. Luckily the rabbits had left enough lettuce to fill Nan’s little wicker basket. Satisfied, Nan gathered up the bounty and started toward the house without a word. John followed. He knew better than to turn aside Nan’s implicit offer of food.

Nan’s kitchen always smelled like home to John. Decades of rich aromatic cooking had steeped into the wood of the cabinets and the piquant scent of frying oil and earthy spices hung in the air like a specter of meals past. It reminded John of his own mother’s kitchen. She had died soon after he graduated high school, and most of his memories of her were dominated by her stalwart cooking. It didn’t take a pop-psychologist to understand his fondness for Nan. John was forty-five now, and Nan had been a part of his life for as long as his real mother had been.

Nan began to wash the vegetables in the sink. She took a moment to look out the window and wondered where Roundboy might be. Nan secretly called the boy Ogan which meant groundhog. Nan had names for everyone in Pin Oak. Most of the names she kept to herself—especially the names she had for the white people living on the hill. Not that she was prejudiced, not really, but the yonega were mostly outsiders, young people with no ties to the community who tended to keep to themselves. The yonega didn’t go to the Pin Oak Baptist Church. They didn’t fish or hunt crawdads down in Cedar Creek. They didn’t play softball or Indian marbles on the community ballfield in the summer. They had no concept of Pin Oak’s Cherokee customs. In Nan’s suspicious mind, the yonega were hiding in their dirty trailers, cooking meth and watching reality TV.

“I heard there was a wake at Anna’s house,” John said as he chose a piece of bread from a basket on the oven. “I haven’t been to one of those since I was a kid.”

“Your mama didn’t have one?” Nan quizzed. Growing up, Nan had been to plenty of home funerals. These days, though, it was a dying tradition. One of many.

“No.” He pulled the bread apart. “I remember going to my Uncle Bird’s wake. I was about four or five. I walked into his living room and there was Bird, stretched out like he was taking a nap. Everyone was sitting around eating and telling stories like it was Thanksgiving. No one warned me there would be a dead body just parked in the corner like furniture. Freaked me out.”

Nan chuckled. “I guess not too many people do that stuff anymore. You know, the funeral director told me Sister was in a better place. Why are white folks always lookin’ for a better place?”

“It’s just something they’re supposed to say.”

“People been coming to this land for five hundred years looking for a better place—still ain’t found it. Well, if there is a better place, what are we doing here?” she sniffed, a clear signal that the subject was now put to rest. “So, how’s the bread?”

“The bread?” John raised his brows. “Fine, Nan.”

She shrugged. Anna May’s frybread was always better than Nan’s, and Nan acknowledged this without spite. Anna had always been the better cook which was just fine with Nan. Nan was the better gardener. But now Sister was gone and Nan was Beloved Woman. She guessed Roundboy would be coming to her for frybread now.

The sisters were born and raised in Pin Oak, never living anywhere else, although Nan once went to Washington, D.C. when her youngest daughter won some kind of school award. Because of that trip Nan had always felt a little more worldly-wise than her big sister. But times sure were changing fast. Anna and Nan were the last of their generation. As the old ones disappeared, so too did their culture. The kids these days were digital and their parents drove electric cars. No one had time for the old ways anymore.

“How’s your boy?” Nan asked as she shook the water from the lettuce.

“Osda,” John smiled. Good. “He’s working on the road. Making money. Found himself a good woman.”

“When you gonna find a good one?”

“I find a good one all the time.” He gave a rakish smile. “But they keep finding out about each other.”

“You and Tommy were just alike,” she laughed. She put the lettuce in a bowl then began to slice the tomatoes and cucumbers. “Always chasing girls.”

“Tommy didn’t have to chase them.”

Nan’s smile was wistful. Her son always had a way with the ladies. “We’ll need some plates,” she said.

John retrieved a couple of colorful plates decorated with chickens. Nan brought over the salad fixings then took her usual seat at the little round dining table. John made his salad. Nan said a quick prayer and they began to settle into their lunch. They ate without talking; the only sounds heard were their chewing and the hum of the refrigerator. When they were done, John cleared the table, dumping the plates in the sink. As he ran the dishwater, he leaned against the counter with his arms crossed.

“Kawi-tsu tsaduliha?” he asked.

“Vv, kahwi agwaduli’a,” Nan nodded, answering before she realized he’d asked her if she’d like some coffee—in Cherokee. She gave him a puzzled look. Most of John’s generation did not speak the language beyond a few quotidian words—hello, how are you?—so she certainly didn’t expect him to correspond in a full sentence. For his part, John turned and opened a cupboard as if nothing was out of the ordinary. Nan decided to test him.

“Tsalagiha hinohvli? Holigas?” Do you speak Cherokee? she queried. Do you understand?

“Goliga,” he responded as he filled the coffee carafe. “Usti giwoni tsalagi. I’ve been taking language lessons for a while at the college.”

Nan smiled and felt her eyes moisten. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I wanted it to be a surprise. It was tough at first, learning all the tenses and the subtle sounds, but I think I’m coming along alright.” He put his hand on Nan’s arm. “I really miss hearing my mom and grandma speak to each other in Cherokee. I realized that if we, as a tribe, don’t do something to educate our young ones, well…Cherokee will just be a name on a casino and nothing more. Maybe you could tutor me?”

Nan rose from the table and joined John at the sink. Her eyes seemed to sparkle with tears. “Hawa,” she agreed as she patted John’s hand. As she rinsed the plates she thought about her own children. None of her daughters spoke more than a handful of Cherokee words, but her grandchildren were taking lessons in school. There was a disturbing paucity of fluent speakers left alive so there’d been a push in recent years to reclaim some of the culture that had nearly been lost completely. Much had been forsaken by John’s generation, but perhaps there was still hope for the young ones. A better place.

And perhaps there was still hope for Pin Oak’s Beloved Woman, too. Nan scooped some flour into a bowl and began a fresh batch of frybread. As she kneaded the dough, she shared with John what Anna May had whispered to her in the ambulance. Through the window she saw Roundboy coming across the yard.

He looked hungry.

Ω

Jamie Cunningham, a Cherokee tribal member (wolf clan), has published in such literary journals as Confrontation and The Iconoclast. He is also an accomplished musician and artist, and has been featured in Guitar World.

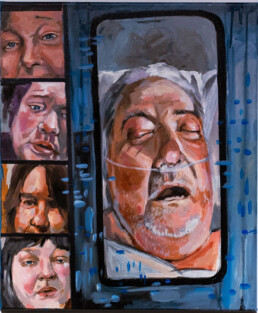

The accompanying image is a painting of Mery McNett’s family on a video call with her father, who was dying in the hospital with COVID. It shows each of them looking at him through a tiny square of video, and his image on the phone, barely conscious. It was the last time McNett spoke to her dad. If you shine a black light on the painting, you will see a hidden message: "I love you, I love you, I love you. Whenever I look in the mirror, I will always see you." These were the last words she ever said to him. The painting is part of a larger multimedia series, titled “Grief and the Full Cup of Joy,” which centers around the death of McNett’s father, and her pet dog, Gonzo.

Lamento decirte

by MICHELLE GLANS

Florida sighed its big wind

and our tree fell,

broke the gate’s iron teeth,

sent so much water into the attic

that we could stand

among damp sheets of paper.

Abuelita held us like a monstrance

to see the eye of Matthew.

We pointed to the graying sun

shadowed by the haze of the hurricane.

We picked up the blown marigolds,

planted their yellow into little red cups

and placed them near the windowsill.

We prayed the rosary

with our hands held together like sap.

I used to think

that fear was one-dimensional

but now I know it is dry lightning

and Cadillac hearses

and the thought of growing older.

Do you remember

that pine tree and all its needles

we liked to pull apart?

You always got the wishes

and saved them for me.

Do you remember Abuelita’s big eyes,

like manzanilla olives in picadillo,

stuck somewhere between

a rainstorm and a sun-shower,

her freckles like orange soda stains,

the sound of her last leaving: that soft,

never-ending jingle of bangles?

Ω

Hanna Wright is a self-taught folk artist residing in Keavy, Kentucky. She uses her experiences growing up in rural South-Eastern Kentucky, teaching special education classes, and living with obsessive compulsive disorder to inspire her unique works of art. She graduated from the University of the Cumberlands in 2015 with degrees in Special Education Behavioral Disabilities and Elementary Education.

Racecar is a Palindrome

by ROBERT REEDY | 3rd Place, student prose contest

The splendor of the world has been enriched by a new form of beauty, the beauty of speed. A racing-car adorned with great pipes like serpents with explosive breath…

—Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944)

Even before I was born, I loved racecars. While pregnant with me, my mother worked on the pit crew for my dad and his co-driver Ernie. They competed in purpose-built cars on actual racetracks. According to Mom, Ernie raced a car that drove me wild. The baritone shout of an un-muffled inline six at full boil, rising amid the roars, pops, and yowls of the other cars always got me going. It wasn’t the volume. I didn’t react at all when other loud cars drove by. But every time Ernie opened the throttle down the front straight, I kicked furiously. I guess I could have hated it. I don’t remember it at all, as my mother hadn’t given birth to me yet. My personal memories of cars start when my brother was about to be born.

The moment has crystalized in my mind.

I was almost five at the time. We lived in a California apartment complex with a covered parking lot. Each space had a little curb at the top, so cars didn’t roll into each other. My mother was going into labor. Dad sprinted to the Jeep while Mom and I toddled over to wait until he brought the car over.

I watched as Dad threw the Jeep into gear, his mustache bristling, gaze intense. He floored the accelerator, and the Jeep lunged straight forward, over four rows of parking curbs, bouncing crazily, directly toward us. I remember it flying, hopping like a frisky billy-goat. It looked as if it was excited to meet the newest member of the family! I thought it was awesome. My mother thought we were going to die; she inched around a steel support beam, in the midst of a contraction.

Luckily, nobody died. Indeed, two things came to life that day: one was my brother, and the other was my belief that cars were alive. That wasn’t a big logical jump for the mind of a child. There are so many complex moving parts in automobiles that many adults are clueless as to how they work. They might as well be alive, or magic, or both. To a small child, cars absolutely qualified as both.

A year later we moved from California to Oklahoma. At that point, the trip was more miles than I had traveled in my entire life. The mover’s truck we used was a totally new experience for me, exotic and special in its novelty. Its sides were billboard signs! Its bulldog nose snorted away loudly under a heap of billboards on its forehead, huge and grumbly, even while parked. The seats were so high, and I could see so far! Its cavernous body concealed our entire life and effortlessly carried it an impossible distance away. Is this alive too?

On that multi-day road trip, we drove down endless arrow-straight sections of desert highway. Riding in the truck with my mother, I asked silly questions, as young children are wont to do. One such question was as old as motor vehicles themselves, perhaps even carriages and wagons, “Mom, can I drive?”

I’d asked the question before and was always met with a smile and a firm, “No.”

That time, I only got the smile.

I stared in growing wonder as my mother’s eyes flicked from the empty stretch of highway ahead to the door mirror and the uninhabited road behind us. To my infinite amazement, she scooted back in the bench seat of the large, fully loaded, diesel-powered moving truck and patted her lap.

“You can sit on my lap and steer. Just keep it going straight between the lines. Hurry up, before I change my mind.”

I was awestruck and overwhelmed. I found my butt on my mom’s lap, staring forward intently, with my hands locked on the steering wheel so that it couldn’t move an inch. I was driving! The truck lazily drifted to the edge of the lane and onto the shoulder.

No truck, I said. Go that way! I’m not moving the wheel!

“Whoa there, keep it straight.” My mother’s hands covered mine as she calmly and gently corrected us back to the center of the lane. This happened twice more, then I found myself back in the passenger seat. Mom explained while she drove. Turns out you can’t just hold the wheel straight; you must wiggle it around to keep the truck between the lines. You had to keep reminding it which way it was supposed to go. The truck moved on its own as if it was a horse. As if it were alive. Incidentally, that very same truck spat its driveshaft—the part that lets the engine move the wheels, more or less—out from under it a few days later, just miles short of our destination. The beast was displeased! In my eyes, cars became wonderful, inscrutable, temperamental creatures, easily angered.

My father stopped professionally road racing when we moved to Oklahoma. He never sold his racecar though. It traveled inside the moving truck with all of our other things. It was a fixture of my early suburban childhood. A pale, oxidized-blue, two-door Fiat gutted and roll-caged, driver net hanging in the window. I never gathered what year or model it was. It was timeless. Its name was Runt. The rare glimpse under Runt’s hood revealed dust and a surprise, four little trumpets pointed at the clouds. A four-cylinder?

“Son, more isn’t always better,” my father informed me when I asked.

Runt was parked behind the garage. That was his home. Runt was always a male in my imagination. Year after year, wasps built nests in him, rain pounded him, snow and leaves hid him from view. He was always there, sleeping behind the garage. Runt was a testament to days long past, and food for my wild imagination. Every time I visited the garage I saw it as his closet, which always held extra tires on extra wheels, hanging on bars from the ceiling, dark and forgotten. Dust powdered the sticky rubber. A forgotten shrine to a slumbering god.

When I was about ten, my father decided it was silly to keep a racecar and never run the engine. If it never ran, it would eventually freeze up. Then it would be completely useless, not compelling enough to justify its own existence anymore. The dreams of one day racing again would be as dead as the car. My mother push-started Runt using the same billy-goat Jeep from the parking lot, and that slumbering god woke once more, tearing its way into the world of the living.

The noise was incredible, cacophonous, and even ugly. If there was a chainsaw the size of a car, I imagine it would sound like Runt. Commuter car engines redline at around six-thousand rpm, Runt’s was something like twelve thousand. And his sound wasn’t the well-organized song of a fast motorcycle. It was a large caliber pistol firing two hundred rounds a second. The sound of tearing paper broadcast on a thousand megaphones. It was the loudest sound I had ever heard, and it was magnificent.

My whole life, Runt had been silent. A sleeping presence in the backyard. Now, his enforced silence had been broken.

Dad didn’t keep him out for long.

“Just enough to stretch his legs,” he later said.

I barely remember seeing him take off, but I will always remember the noise. Runt shouted down to the corner and turned into the neighborhood behind our house. Then there was an unholy roar. I could hear Runt tear down the street, unable to see him, but tracking his progress easily. Another corner, another bold roar. The final stretch seemed to go on longer than the others, as if Dad kept the throttle open just a little longer, unwilling to end the moment. I remember the gravel popping beneath weather rotted tires as Runt rolled into the yard, still chattering away at four-thousand rpm even while idling. Then it was over, and the only sound left was the ringing in my ears. Runt’s silence echoed once again.

We moved again to another city in Oklahoma, and my dad’s attention shifted to dirt-track racing—which was much cheaper than road racing. Runt lived behind the garage at our new house too and would be largely forgotten for years, waiting for someone to wake him again. My imagination also moved on to other things, like the alcohol dragster down the street.

Incidentally, there was another racecar and driver in our new neighborhood. Our family called him ‘Racecar Ralph’, though in my imagination, his name will always be Alcohol Dragster Guy. As the names imply, he had an NHRA racing license and a long-body alcohol-fueled dragster like the ones on TV. That exotic beast lived behind a wrought iron fence, like a dangerous predator at the zoo. I never saw the dragster in a race, or even move on its own. It was only practicing, like a lion cub who just can’t wait to be king. When you race a car regularly, you must work on and test the engine. Dragster exhaust pipes are just little tubes to get the flames away from the motor, they have no muffler. So, whenever Ralph tested the motor, the whole neighborhood knew, and I came running. Racecar Ralph was friendly and patient with excitable children asking endless questions.

It amuses me to think that the dragster might have intimidated poor Runt. The noise it made was glorious, truly the sound of an angry god. Much, much louder than anything else I had heard in my life. It put Runt’s buzzing to shame! It was like constant thunder, a lightning storm overhead despite clear skies. Even with my hands covering my ears, it was impossibly loud. I felt it. My whole body, my vision itself—my eyeballs—shook! Every time I watched or listened to that car I was awestruck. That car didn’t live in my backyard though; it wasn’t my car. That car wasn’t Runt.

Around that same time, my father teamed up with a coworker to race on dirt tracks for some years. It was real racing, but much more affordable than road racing for a father of two. Many types of cars, all racing in different classes with other, similar cars. They tore around a clay oval, like tiny, muddy NASCARs.

I learned that welding is like car surgery. I saw a car go from salvage to race-ready in a few months. Then we got to spend time at the dirt track! Racecars in various states of assembly were everywhere, wrenches turning to the constant backdrop of announcer chatter and engines. Trucks, trailers, pit bikes, ATVs—the racetrack had everything a growing boy could ever want. There was racing too. I mostly ignored that. I learned to appreciate circle racing much later in life, but at the time it held little interest for me. I wanted to explore the pits constantly! It was absolute heaven for a nerdy, ADHD preteen. Secretly, I was searching for another Runt. Did any of these people have pet racecars? I honestly don’t remember if dad or his partner ever won a race on dirt.

The last time I saw a racecar in person, I was a young teenager. Dad had waited years, but finally, it was time to justify Runt’s existence again. Billy-goat Jeep was long gone by this point, so a neighbor attached a tow strap from Runt’s front tow hook—an especially useful feature all racecars have—to his truck’s trailer hitch. I watched from the curb as the tow strap tightened and the cars rolled forward. Dad eyed the speedometer and threw the car into gear at the proper speed. The rear wheels chirped as the engine coughed, sputtered, and roared. Runt wasn’t as loud as I remembered, but it was still an unholy noise. They shook the tow strap loose, and dad raced to the end of the street. Then he stalled the engine, and Runt sputtered out again.

They reset their positions; the tow strap tightened. Just once around the block to make sure it’s still working! There was one fateful cough from the exhaust, then the mournful shriek of protesting rubber as Runt’s little engine seized completely. The truck was still pulling at fifteen or twenty miles per hour when it happened. The inertia, the mass, the sheer force involved, still tried to turn the rear wheels, but the engine itself had frozen entirely. Something had fused together or broken to lock it in place. The engine could not turn, and that force had to go somewhere. In a desperate last stand, Runt lifted on his hind wheels in a mockery of a wheelie, his body twisting somehow, even though he had a roll cage. I distinctly remember the tow strap creaking with tension, like a tree mid-fall, stretching perilously close to snapping. I ran towards the back of the truck, in a misguided attempt to pop the tow strap loose. All I could think at the time was that Dad was in trouble.

That moment was the first time I ever saw my dad genuinely panic. He raised his hands from the steering wheel, hanging from his racing harness and seat, and gestured at me wildly. His eyes were white all the way around, and he shouted so forcefully that spit sprayed from his mouth, “Get away! Get back! BACK!” I ran back to the lawn, shocked and overwhelmed.

They quickly sorted out the situation. The truck backed slowly to lower the car to the ground, then retrieved a trailer to move Runt out of the road. That day I learned that straps under tension could snap violently, and even kill. I learned something else too. I knew years before that day that cars weren’t alive, just incredibly complex machines. However, that day some of their magic died. They were no longer mythological creatures, temperamental and tempestuous. I learned that cars could die.

Years passed by. I grew up, spent time in prison, and then moved away. I didn’t buy my first car until I was in my early twenties. A 90s hatchback. Her name was Reba because I could never properly remove the Reba McIntire bumper stickers that had baked onto the poor car over fifteen years of sun. Her red paint was even more oxidized than Runt’s paint from my childhood memories. I bought Reba from her previous owner for the princely sum of one hundred dollars, which my boss loaned me. Very early on in car ownership, a combination of the flu and sleep deprivation led me to have an accident. Reba got thrashed but was still drivable. The passenger side doors didn’t open anymore. I stopped babying my car after that. Reba and I explored the mechanics of car control and the limits of performance by driving incredibly irresponsibly on the dirt and gravel county roads around my town.

Though it had been years, I began to feel the magic again! Slowly, as we played and explored, Reba and I found the secret of racing. We found the reason it exists. It is the sheer visceral sensation of driver and machine working as one. The feeling of your insides moving and shifting in response to the car. The ‘seat feel’ that drivers talk about. When driver and car become as one, they are far more than the sum of their parts. They become a new animal, a racecar.

The spell broken in my childhood sparked into life once again. The embers of memory flared into the fires of passion. Like the Olympic flame, the dream was passed on to another. From then on, whenever I was driving, in my heart, I was part of a larger whole. A racecar. Runt would be proud.

Ω

Robert Reedy is currently pursuing his second Associate’s Degree at TCC. He is 35, married, and incarcerated at Dick Conner Correctional Center. He hopes to write professionally in some capacity.

Jamie Cunningham, a Cherokee tribal member (wolf clan), has published in such literary journals as Confrontation and The Iconoclast. He is also an accomplished musician and artist, and has been featured in Guitar World.

Sonnet as Testament to the Orange Tree

by SOPHIA ZHAO

This is how our history begins: an orange tree folded into

pasture, sunrise sifting through its leaves—

a soft spill onto the ground, and light finally reaches the hole

where Baba lives. Every spring a full bowl, a rabbit run,

and a cluster of pale bodies grows sticky and saccharine.

Every spring throats crimping into warm pockets,

gathering blessings behind worldview. Orange

as holy beads. Orange as prayer answer. When the branches

finally knot together, hand-in-hand, Baba makes

a pair of palms out of his back. To sift under the light is to grow

tender, stomached down by hunger and heat.

Sometimes, Baba is a wet mound among the grasses,

in a quick second swallowed by the hills— except

he doesn’t scream, like a lapping bird swept into water.

Ω

Sophia Zhao is from Newark, Delaware. Her paintings and poetry appear in The Adroit Journal, Up the Staircase Quarterly, The Minnesota Review, and elsewhere. She currently studies at Yale University.

Beth Horton holds a degree in creative arts therapy and majored in health science at Niagara University, located near Buffalo, New York. Beth began working with monochrome imagery in her late teens, but her love for art began as a small child, watching her father paint into the wee hours of the morning. On weekends, she ventures out into the world around her to document the shape of her space in black and white.